Previously on Prolog’s Role in the LLM Era, I discussed:

- Making a case for partnering fuzzy LLMs with deterministic rules.

- Positioning this blog as what is really “Appendix C” of my book, Enterprise Intelligence.

- Prolog as an alternative RDF-based Knowledge Graphs.

- Prolog processed with a Prolog engine as well as Prolog as unambiguous parts of an LLM prompt.

- The big picture use case for Prolog in partnership with large language models (LLM).

- How authoring Prolog with assistance from LLMs opens the door to that vast majority of people whose voices don’t contribute to the commercial LLMs.

- The basics for working with Prolog in a Python environment with SWI-Prolog and pyswip.

- A few implementation techniques, for example, using LLMs to generate a short description from which we create an embedding and add to a vector database.

- Importing rules from machine learning (ML) models as a source for automatically generated rules.

I do recommend reading Part 1 through Part 4 first.

In this episode, we integrate Prolog with our conventional OLAP (Business Intelligence, BI) and even OLTP databases:

- OLAP – On Line Analytical Processing – the highly-curated, user-friendly, and highly-performant Business Intelligence (BI) for analytics.

- OLTP – On Line Transactional Processing – the databases used to run your business processes. This includes among many others, the ERP, SCM, CRM systems. Most large enterprises employ at least a few dozen to hundreds of OLTP systems that support that many business processes or use cases.

The Figure below shows the aspects of AI we’re covering in this series. Whereas the previous episode is about merging machine learning (ML) with the Yin (more “intuitive”) and Yang (more logical) pairing of LLMs and Prolog, this episode is about merging traditional Business Intelligence (BI):

OLTP and OLAP

OLAP databases are the BI databases which include data warehouses, data marts, OLAP cubes, and data vaults. These databases generally don’t include the absolute latest data. But they are optimized for the needs of analysts (easy to access and understand, and highly-performant). The processing of these highly-curated BI databases can be very extensive, so they are generally updated in batches at scheduled times – for example, late at night when utilization of the underlying OLTP databases is low.

OLTP databases reflect the most current state, the latest and greatest, of our enterprise data. The logical Prolog can make its deductions on the most up-to-date data – barring any data that hasn’t been key-punched or entered by data input people from paper receipts. Hahaha.

MetaFacts vs. MetaRules

In Part 4, we explored how to import rules from ML models (mostly created by data scienctists) into Prolog as automatically generated MetaRules. Similarly, we’ll import up-to-date and highly-curated data from OLTP and OLAP databases as MetaFacts, creating a more dynamic system:

- Mix and Match Mechanism: Allows for flexible rule application.

- Real-Time Data Inclusion: Incorporates the latest data at query time.

- Efficient Data Handling: Prevents Prolog from being overloaded by materializing only necessary data into Prolog in an as-needed basis, avoiding large datasets in memory.

The concept of MetaFacts is simpler than MetaRules discussed in Part 4. Facts are just elements of data—static, defined pieces of information that Prolog can use directly. In contrast, rules are about the relationships and logic that govern how facts interact. Rules require much more intellectual investment to compose. Performing deductive reasoning versus learning of the result of a deduction are two very different things – like chess versus tic-tac-toe.

MetaRules dynamically generate these relationships, enabling more complex reasoning and adaptability within the system. This makes MetaRules not just a way to include data but a method to create and apply logic that evolves with the data, adding significant complexity and power to the system.

Clashes of the term, “MetaFacts”

In 2004, I coined the term “MetaFacts” when developing my Prolog variant (SCL). While other entities have since adopted the term “MetaFacts” (and Metaphacts) in the analytics space, their usage seems to relate more in the context of their company branding. In contrast, I use MetaFacts in the context of a feature within Prolog, focusing on enhancing its distributed capabilities, unlike the traditional monolithic database approach. In my book, Enterprise Intelligence, I explore how data mesh principles, often applied to BI databases, can similarly benefit Prolog in creating distributed, domain-level knowledge graphs.

Existing MetaFact Capability

The idea of integrating Prolog with traditional databases isn’t nearly as novel today as it was back in 2004. I’m simply sharing what I’ve done. Since I’ve been using SWI-Prolog for this series, I initially investigated what built-in features it might have in regard to the ability to dynamically query outside databases for latest and greatest facts and/or rules.

SWI-Prolog does provide extensions for importing facts from various types of databases. This includes support for SQL databases, NoSQL databases, and integration with other data sources. These extensions allow you to connect to external databases, execute queries, and import the resulting data as Prolog facts. The most commonly used library for this purpose is their ODBC (Open Database Connectivity) interface, which allows SWI-Prolog to interact with SQL databases.

However, I decided to go ahead without incorporating SWI-Prolog’s implementation of this capability for two reasons:

- I wrestled with it for more than a few hours and couldn’t get it to work. Explaining what happened is a blog in itself. I’m sure it works well, but I don’t have the time to work it out at the time of writing. I’ll revisit it some time later.

- Capabilities like MetaFacts do not appear to be a part of ISO Prolog. Not all flavors of Prolog would implement this feature in the same way. So my intent is to present the idea in a more generic approach using Python to generate Prolog using “standard” Prolog syntax.

For now, I’ll demonstrate the notion of MetaFacts using Python that integrates the ODBC functionality in the pyodbc libary and the Prolog functionality of Yuce Tekol’s pyswip Python library (wrapper over SWI-Prolog).

MetaFacts Walkthrough

This walkthrough demonstrates how to generate Prolog files from metadata. The metadata includes a database query (usually SQL to an RDBMS), connection details, and the order of columns, which determines the sequence of terms in the Prolog facts generated from each row.

Once the Prolog facts are generated from the metadata, they can be integrated with other Prolog files containing additional facts and/or rules. This merging process allows you to create a more comprehensive and robust knowledge base, where the newly generated facts can interact with existing rules and facts. By combining these Prolog files, you can leverage Prolog’s inference engine to perform complex queries, infer new relationships, and automate decision-making processes, ultimately building a robust, rule-based AI system.

This MetaFacts walkthrough will demonstrate how Prolog implemented in a loosely-coupled, modular fashion allows for seamless integration of diverse facts and rules from multiple domains. By leveraging Prolog, you can mix and match rules from different experts, enabling the creation of a dynamic and adaptive AI system. Furthermore, this approach supports the gradual transformation and segmentation of rules, accommodating both rapidly changing facts and more static knowledge.

Finally, integrating Prolog MetaFacts with a vector database, as outlined in Part 3, ensures that all facts and rules are robustly searchable, providing a powerful, scalable knowledge management solution.

Development Environment

Part 3 of this series describes the development environment required for the exercises. In a nutshell, you need Visual Studio Code, Python 3.10+, the pyswip Python Prolog library, and SWI-Prolog.

You will also need Microsoft’s ubiquitous sample SQL Server database, AdventureWorksDWxxxx. The examples just use DimCustomers and FactInternetSales, so a variety of versions will probably work. But I’m using AdventureWorksDW2017.

The code used for this walkthrough can be found in the GitHub repository supporting Enterprise Intelligence. The primary Python code is: metafacts_multiple_resultset.py. It’s too much to list the entire code in this blog, but I will display the necessary snippets.

Exercise 1: Single Result MetaFact

The following Json file, metafacts_single_resultset.json, holds the metadata for this exercise. It consists of:

- Connection information to an AdventureWorksDW2017 database on a SQL Server instance -server and database keys.

- A sql query where each row will be formatted into a Prolog fact. In this case, it’s a query to the DimCustomer table.

- A set of predicates and a list of columns defining the order of the respective row value by which the fact will be formatted. In this exercise, the resultset_predicates key consists of a list of one predicate: customer and its customer key, first name, and last name, in that order.

- A description that could be added to a vector database for contextually robust searching.

{

"server": "<sql server database name>",

"database": "AdventureWorksDW2017",

"sql": "SELECT CustomerKey, FirstName, LastName FROM DimCustomer WHERE CustomerKey BETWEEN 11000 AND 11010",

"resultset_predicates": {

"customer": ['CustomerKey','FirstName','LastName']

},

"description": "Retrieve a sample set of customers from AdventureWorksDW"

}

The segment in the json above, “customer”: [‘CustomerKey’,’FirstName’,’LastName’], could alternatively have been, “customer”: [], which would default to the order specified in the SELECT statement.

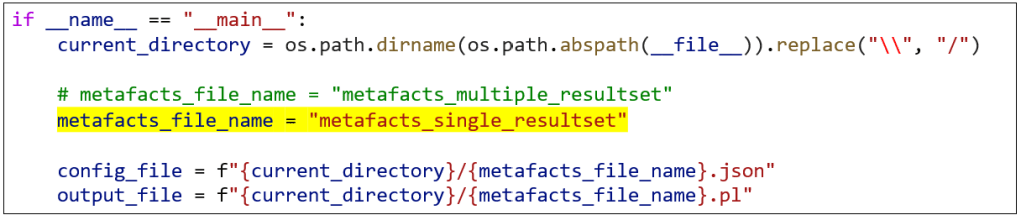

The code snippet below from metafacts_multiple_resultset.py shows we are using metafacts_single_resultset.json as the metadata for our MetaFacts.

The code snippet below, also from metafacts_multiple_resultset.py, shows the primary steps of:

- Connecting to the AdventureWorksDW2017 database on the specified SQL Server instance.

- Executing the SQL on the database and retrieving the result set.

- Running the process_result_sets function which will transform the cursor data into a set of Prolog facts.

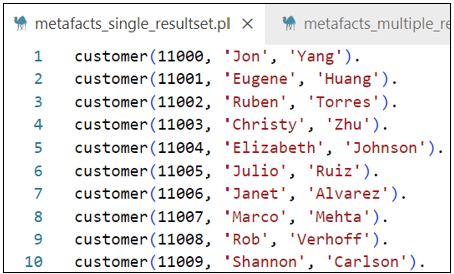

As process_result_sets iterates through the resultset from AdventureWorksDW2017, the transformed Prolog fact is printed:

Asserting: customer(11000, 'Jon', 'Yang')

Asserting: customer(11001, 'Eugene', 'Huang')

Asserting: customer(11002, 'Ruben', 'Torres')

Asserting: customer(11003, 'Christy', 'Zhu')

Asserting: customer(11004, 'Elizabeth', 'Johnson')

Asserting: customer(11005, 'Julio', 'Ruiz')

Asserting: customer(11006, 'Janet', 'Alvarez')

Asserting: customer(11007, 'Marco', 'Mehta')

Asserting: customer(11008, 'Rob', 'Verhoff')

Asserting: customer(11009, 'Shannon', 'Carlson')

Once all the Prolog facts are created, a unit test is run that shows the Prolog is queryable as expected. The first line is the Prolog query to fetch all customers along with their customer key, first name and last name. Below that first line are the results:

Executing query: customer(Customerkey, Firstname, Lastname)

{'Customerkey': 11000, 'Firstname': 'Jon', 'Lastname': 'Yang'}

{'Customerkey': 11001, 'Firstname': 'Eugene', 'Lastname': 'Huang'}

{'Customerkey': 11002, 'Firstname': 'Ruben', 'Lastname': 'Torres'}

{'Customerkey': 11003, 'Firstname': 'Christy', 'Lastname': 'Zhu'}

{'Customerkey': 11004, 'Firstname': 'Elizabeth', 'Lastname': 'Johnson'}

{'Customerkey': 11005, 'Firstname': 'Julio', 'Lastname': 'Ruiz'}

{'Customerkey': 11006, 'Firstname': 'Janet', 'Lastname': 'Alvarez'}

{'Customerkey': 11007, 'Firstname': 'Marco', 'Lastname': 'Mehta'}

{'Customerkey': 11008, 'Firstname': 'Rob', 'Lastname': 'Verhoff'}

{'Customerkey': 11009, 'Firstname': 'Shannon', 'Lastname': 'Carlson'}

Below is the end product, a file named metafacts_single_resultset.pl:

The file, metafacts_single_resultset_rules.pl, contains a rule determining if a customer is high risk along with a few other facts about two customers:

% Define the rule for classifying a customer as high-risk

high_risk_customer(CustomerKey, FirstName, LastName) :-

customer(CustomerKey, FirstName, LastName),

credit_score(CustomerKey, Score), Score =< 600,

annual_income(CustomerKey, Income), Income =< 50000.

credit_score(11009,800).

annual_income(11009,120000).

credit_score(11000,550).

annual_income(11000,45000).

The Prolog facts generated from the metafact could be merged with those rules.

Exercise 2: Multi-Resultset MetaFacts

This exercise expands from Exercise 1, where we made a single query. In this exercise we look at making multiple queries to a database in one call. This is accomplished through the use of stored procedures, a powerful feature in databases like SQL Server, Oracle, and Snowflake, offering several advantages:

- Push-Down Logic: By pushing down logic to the server, where the data resides. This processing logic near the data approach allows the server to optimize data processing, reducing the need for extensive data transfer between the client and server.

- Performance: Precompiled for optimized execution speed.

- Reduced Network Traffic: Encapsulate multiple operations, including returning multiple result sets in one call, minimizing communication.

- Security: Control access and obfuscate code.

- Centralized Logic: Centralize business logic for consistency and simplified maintenance.

This exercise uses the same Python, metafacts_multiple_resultset.py. That code already handles calls to database stored procedures. The main differences are in the resultset_predicates element of the configuration file:

- The sql element is a call to a stored procedure rather than a single SQL.

- The resultset_predicates element has more than one item.

{

"server": "<sql server database name>",

"database": "AdventureWorksDW2017",

"sql": "EXEC usp_GetCustomerOrders",

"resultset_predicates": {

"customer": ["CustomerKey", "LastName", "FirstName"],

"sales_order": []

},

"description":"retrieve selected customers and sales ordered from AdventureWorksDW"

}

Below is the stored procedure specified in the “sql” parameter of the above json, usp_GetCustomerOrders:

CREATE PROCEDURE [dbo].[usp_GetCustomerOrders]

AS

BEGIN

-- First result set: Basic customer information

SELECT TOP 10 CustomerKey, FirstName, LastName FROM DimCustomer

WHERE CustomerKey BETWEEN 11000 AND 11010;

-- Second result set: Basic order details

SELECT TOP 10 CustomerKey, SalesOrderNumber, OrderDate, SalesAmount FROM FactInternetSales WHERE CustomerKey BETWEEN 11000 AND 11010;

END;

The stored procedure needs to be created to the AdventureWorksDW2017 database. It generates two result sets – one similar to the customers from Exercise 1 and sales orders for the customers.

Once it’s added, we select the metafacts_multiple_resultset.json file as our metadata. Again in metafacts_multiple_resultset.py, we comment out metafacts_single_resultset and uncomment metafacts_multiple_resultset:

Running metafacts_multiple_resultset.py, generates this Prolog file.

The customers and sale orders in that Prolog we just created (metafacts_multiple_resultset.pl) could be combined with these business rules:

% Rule to find customers who have made a purchase over a certain amount

high_value_customer(CustomerKey, FirstName, LastName, SalesAmount) :-

customer(CustomerKey, FirstName, LastName),

sales_order(CustomerKey, ,_, SalesAmount),

SalesAmount > 3380.

% Rule to check if a customer has multiple sales orders

repeat_customer(CustomerKey, FirstName, LastName) :-

customer(CustomerKey, FirstName, LastName),

sales_order(CustomerKey,_, OrderDate1,_),

sales_order(CustomerKey,_, OrderDate2,_),

OrderDate1 \= OrderDate2.

The customer and sales order facts exist independently of the two business rules. They have a loosely-coupled relationship.

The test Python, test_multiple_set_prolog_rules.py, is a unit test for the combination of the MetaFact and the high_value_customer and repeat_customer rules. This is the core of the script that loads the facts and rules, and runs a test query. Note the highlighted row. It’s a 2nd sales order fact for customer 11006 so we have at least one “repeat customer” for the repeat_customer rule:

Here are the results of that script, with apologies for 11006 appearing twice. Seven of the customers are high value and one is a repeat customer:

Calculated Measures as Rules in Prolog

We’ll complete this investigation of merging BI with Prolog with a short discussion on calculated measures. These are the kinds of custom calculations that BI tools like SQL Server Analysis Services (SSAS) cubes or Power BI allow you to define. Typically, they are written using languages like MDX (Multidimensional Expressions), DAX (Data Analysis Expressions), and of course, SQL.

What’s fascinating is that these calculated measures are, at their core, rules—rules that define how certain values should be computed based on other values. These rules expressed as formulas can be integrated with the more robust predicate-logic rules of Prolog. Most calculations can be expressed as logical expressions (Prolog) as well as words (LLMs).

From MDX to Prolog

Consider a typical calculated measure in an SSAS cube, such as:

-- Profit margin is sales less freight as percent of revenue.

-- From the AdventureWorks2017 SSAS cube.

[Measures].[Profit_Margin] = ([Measures].[Sales Amount] - [Measures].[Freight]) / [Measures].[Revenue]

This MDX expression calculates the profit margin by subtracting the freight cost from the sales amount and then dividing by the total revenue. This can be seamlessly converted into a Prolog rule, allowing the logic to be reused and reasoned over in a different context.

We can ask a ChatGPT to transform the MDX calculated measure above into Prolog, along with some commentary:

please transform this calculation into a prolog and create a caption in the prolog based on all the comments and formula:

-- Profit margin is sales less freight as percent of revenue.

-- From the AdventureWorks2017 SSAS cube.

[Measures].[Profit_Margin] = ([Measures].[Sales Amount] - [Measures].[Freight]) / [Measures].[Revenue]

Here’s how that MDX expression might look as a Prolog rule along with helpful commentary composed by the LLM:

% Profit margin is calculated as sales amount less freight, expressed as a percentage of revenue.

% This rule is derived from the AdventureWorks2017 SSAS cube.

profit_margin(SalesAmount, Freight, Revenue, ProfitMargin) :-

ProfitMargin is (SalesAmount - Freight) / Revenue.

With this rule in Prolog, you can now query the profit margin based on the sales amount, freight, and revenue—just as you would in your BI tool, but with the added flexibility of Prolog’s reasoning capabilities.

Leveraging LLMs for Conversion

The process of converting SQL, MDX, or DAX expressions into Prolog rules might seem complex, but it’s precisely the sort of task that LLMs excel at. Such calculations are relatively terse and very literal – which can make life easier for an LLM. So given a SQL, MDX or DAX expression, an LLM can with relative reliably translate it into a Prolog rule, allowing BI professionals to extend their calculations into the realm of logic programming with minimal friction.

This capability opens up exciting new possibilities. BI calculations, traditionally locked within BI “tools” like SSAS, Kyvos Semantic Layer, Tableau, or Power BI, could be exported into a broader, more versatile environment. By doing so, we can mix and match these rules with other Prolog rules, creating a highly customizable and powerful decision-making system.

At the least, we can integrate the context, semantics, and specifics of very many business rules scattered across a number of BI and Analytics databases.

Conclusion

In this episode and the previous one, we’ve explored the integration of Prolog with various data sources and the powerful capabilities it unlocks when combining ML models, conventional databases, and advanced reasoning techniques. By importing MetaFacts from OLTP and OLAP systems, merging them with MetaRules derived from ML models as well as manually authored rules, we can build dynamic and intelligent systems taking us further down the path towards smarter, real-time decisions. This approach not only optimizes data processing and logic application but also lays the groundwork for a more distributed and scalable AI framework, fully leveraging the strengths of both Prolog and modern database technologies.

In Part 6, we’ll take a break from code and dig into some intuition for the value of Prolog.

Update (March 3, 2026)

I’d like to clarify some terminology used in this post. When I refer to “OLAP cubes”, I’m specifically highlighting the multidimensional data structure optimized for analytical queries—distinct from relational databases traditionally geared toward OLTP (Online Transaction Processing) patterns. Kyvos originally built on this OLAP foundation for high-performance analytics at scale (ca. 2015). However, the Kyvos platform has since evolved into a comprehensive semantic layer that delivers a unified, consistent business view across disparate data sources—ensuring “one view, one meaning” for metrics, dimensions, and relationships enterprise-wide. This semantic model retains the core acceleration structures for query speed and efficiency—even more valid today as multiple factors expand the need for trusted data—while expanding to support modern AI-driven insights, data mesh, and enterprise intelligence frameworks. OLAP described how it accelerated analytics. Semantic model describes what it represents. For the latest on Kyvos, check their official resources at kyvosinsights.com.