In my book, Enterprise Intelligence, as part of sharing the “intuition” for the book, I describe a Prolog interpreter I wrote back in 2004. I called it SCL for “Soft Coded Logic”. Its tagline was “Decoupling of logic and procedure”. I created SCL as one of the tools I needed to build a SQL Server performance tuning expert system–a digital twin of me.

A few AI Winter/Summer cycles ago (1980s), Prolog was the “Transformer Architecture” (foundation of today’s LLM) of its time. That was the cycle of the “expert systems”. However, they are profoundly different. Transformer Architecture automatically transforms tons of data (mostly text) into a inferential knowledge base, a large language model (LLM). An LLM such as ChatGPT is an aggregation of our vast written knowledge. We can ask the LLM a question on most subjects and it provides a reasonably good answer most of the time.

On the other hand, Prolog (an acronym for PROgramming in LOGic) is a combination of “code” (rules) and data into a deterministic knowledge base (KB), painstakingly authored by people (subject matter experts and people who know Prolog). In essence, Prolog could be thought of as a declarative programming language centered around logical Boolean IF-THEN-ELSE statements.

LLM models and Prolog KBs have their pros and cons as AI knowledge bases when compared to each other. Most importantly, LLMs models are trained and Prolog KBs are programmed. The notion of training an LLM model is similar to that of training a new skill into your human brain. We have no direct control over the synapse wiring in our brains as we are trained. We train our brain indirectly mostly through cycles of repetitions of exercises and observations and adjustment tweaks over a period of time–like the proverbial ten thousand hours.

Building a Prolog KB is a programming/engineering effort where we directly control the encoding of information. As LLMs are an amalgamation of humanity’s massive corpus written text, Prolog KBs are an attempt to encode the knowledge of subject matter experts. Because Prolog is code (an encoding of subject-verb-object facts and rules), it’s deterministic and traceable. Meaning, given the same query applied to the same data, it will return the same answer. And we can clearly trace how the answer was arrived at.

A great way to differentiate the two is to think of these two dialogs I use in classes that I teach. For programming:

- Me: What is the best thing about computers?

- Class: They do exactly what you told them to do.

- Me: What is the worst thing about computers?

- Class: They do exactly what you told them to do.

For LLMS:

- Me: What is the best thing about LLMs?

- Class: They respond in a robust manner.

- Me: What is the worst thing about LLMs?

- Class: They respond in a robust manner.

Meaning, there is a time and place for the rigid determinism of direct control of programs and a time and place for the versatility of LLMs. Specific answers to specific questions versus inferred answers from questions stated with some level of ambiguity (i.e. the natural language we use to communicate with each other).

So does Prolog have a place in the LLM era? Our brains evolved to handle the complexity of the world we live in. But when we’re able to notice and articulate patterns within the complexity, we have well-defined rules that can be automated. Those well-defined rules don’t require our sentient and sapient brains.

Notes:

- This is a TL;DR of Enterprise Intelligence, available at Technics Publications and Amazon. If you purchase the book from the Technics Publications site, use the coupon code TP25 for a 25% discount off most items (as of July 10, 2024).

- Quick shoutout to Lisp, the “other AI language”. That’s another story.

- This blog is really “Appendix C” of my book. It is an alternative approach to RDF-based Semantic webs, which is the path I chose to cover in the book. But this appendix missed the deadline and was left on the cutting-room floor. You can also read Appendix B that also didn’t make it.

- This blog is Chapter VII.1 of my virtual book, The Assemblage of Artificial Intelligence.

Prolog Background

Programmers over 50 years old might remember Prolog from the 1980s and even into the 1990s. It was the age of expert systems (symbolic encoding of knowledge), a different path from the approach that began with the perceptron in the 1950s, to multi-layered neural networks, back propagation, deep-learning, eventually leading to the colossal neural-network LLMs of today. Like Fortran and COBOL, other dinosaurs from a few eras ago, Prolog (and Lisp) are still in modest use today.

Most of those who recognize Prolog when I mention it recall it fondly. It’s an elegant language:

- The data, rules, and query language in Prolog share a unified syntax.

- Each fact and rule can be stated intuitively, mirroring the subject-verb-object structure found in some variation in natural languages and now encoded in RDF triples.

- Prolog is logically robust, exemplifying Boolean logic. It also supports the formation of ontologies and has built-in support for recursion.

Here is a very simple Prolog snippet:

likes(eugene, grapes).

yummy(grapes).

yummy(shrimp).

interestedproduct(eugene, @thing) :-

likes(eugene, @thing), yummy(@thing).

The English translation is:

Eugene likes grapes.

Grapes are yummy.

Shrimp are yummy.

The products Eugene is interested in including things he likes that are yummy.

ChatGPT does understand the Prolog version of the knowledge. I asked it:

Given this Prolog, which products is eugene interested in? Please respond with just the final answer.

likes(eugene, grapes).

yummy(grapes).

yummy(shrimp).

interestedproduct(eugene, @thing) :-

likes(eugene, @thing), yummy(@thing).

It responded as I had hoped:

interestedproduct(eugene, grapes).

In a new session I gave it the English version:

Based on the following facts only, what products is Eugene interested in?

Eugene likes grapes.

Grapes are yummy.

Shrimp are yummy.

The products Eugene is interested in including things he likes that are yummy.

Despite specifying “Based on the following facts only” and explicitly defining what “interested” means. it didn’t respond the way I had hoped. It included shrimp, which I didn’t mentioned as liking:

Based on the given facts, Eugene is interested in grapes and shrimp, as both are things he likes that are yummy.

I followed up stating that it’s not mentioned that Eugene likes shrimp. It then returned the correct answer. But how valuable is that if it made a mistake with such a simple query?

I asked it again (in a new session) with the exact prompt of English facts and rules, but this time instructing it to think like a Prolog interpreter (prompt engineering hack):

Based on just the following facts, what products is Eugene interested in? Think like a Prolog interpreter:

Eugene likes grapes.

Grapes are yummy.

Shrimp are yummy.

The products Eugene is interested in including things he likes that are yummy.

It provided the correct answer:

Based on the given facts and the Prolog-like logic:

- Eugene likes grapes.

- Grapes are yummy.

- Shrimp are yummy.

- The products Eugene is interested in include things he likes that are yummy.

We can deduce the following:

- Since Eugene likes grapes and grapes are yummy, grapes are a product Eugene is interested in.

- Shrimp are yummy, but there is no information indicating that Eugene likes shrimp.

Therefore, the products Eugene is interested in, based on the given facts, are grapes.

Note that ChatGPT said, “We can deduce the following”? I discuss Prolog and deductive reasoning in relation to inductive and abductive reasoning in Exploring the Higher Levels of Bloom’s Taxonomy.

Although that prompt engineering tweak of instructing it to act like a Prolog interpreter worked, I can’t trust that it will work all of the time. We don’t have control over the material any given LLM is trained on nor anything that happens between clicking the send button and receiving a response. Perhaps the creators of the LLM decided not to burden the LLM with knowledge of dinosaur languages. I don’t know how my prompt specifications will interact with the LLM model and other moving parts. LLMs aren’t like code we develop, test, deploy to production, and monitor on specific metrics.

It doesn’t seem that ChatGPT has access to a Prolog interpreter at this time. I confirmed that with ChatGPT, asking:

Do you use a Prolog interpreter to answer questions I pose with Prolog rules?

Its response:

No, I don’t use a Prolog interpreter directly. Instead, I interpret the logic rules you provide and reason through them to give you answers. My responses are based on the principles and syntax of Prolog but are generated by my language model capabilities. If you provide Prolog rules and facts, I can help you understand and apply them as a Prolog interpreter would.

ChatGPT does employ a number of external tools outside of the LLM itself to assist in its response. The most well-known and obvious include:

- Python: For calculations, data analysis, and visualizations.

- Browser Tool: For retrieving real-time information from the web.

- DALL-E: For generating images based on textual descriptions.

Prolog isn’t among those external tools. What it can do well is translate from one language to another. While it doesn’t use a Prolog interpreter, it is does know how declarative Prolog equates to English (or other natural languages or even coding languages such as Python) and can simulate the behavior of a Prolog engine.

ChatGPT’s ability to translate from unambiguous code (Python, Java, R, SQL, Cypher, etc.) to easily digestible natural language is the key to how ChatGPT seems to process Prolog well – at least at the small scale I’ve been playing with. But, as I say in my BI classes, “Everything works well at small scale.” I learned that the hard way.

What About Knowledge Graphs and the Semantic Web?

Before continuing, I need to address a possible elephant in the room, which are Knowledge Graphs (KG), particularly those encoded to the W3C’s RDF (Resource Description Framework) and OWL (Web Ontology Language – yes that’s WOL) Semantic Web standards.

There is much presented in blogs and YouTube about the symbiotic relationship between LLMs and KGs. LLMs can assist in building KGs by extracting and structuring information into graph structures or even code from its vast training text, while KGs can ground LLMs in reality by providing accurate, structured data to enhance their responses.

Much of the benefit of the relationship between LLMs and KGs is similar to what I present here but substituting Prolog KBs for KGs. So, which way do we go? LLMs partnered with KGs or LLMs partnered with Prolog KBs?

The TL;DR: Forced into a choice today, I’d forget Prolog and focus on KGs built using RDF/OWL standards as a description of relationships and SWRL for defining rules that infer new information from existing information.

Wow. So why read the rest of this blog? First off, that is a narrow decision. I believe that surveying how Prolog might fit into this current LLM-focused AI era provides insight into decoupling between the worlds of clearly-defined mechanistic rules versus the complex and fuzzy world in which we all live.

Recall that I call this blog “Appendix C” of my book. In my book, I chose to go with KGs instead of Prolog to avoid adding another 100 pages to the book. Similarly, I went solely with Neo4j in my book instead of addressing Neo4j and Stardog (the follow-up book will focus on Stardog). The symbiotic relationship between LLMs and KGs plays a chunky role in my book. The growth in interest of Semantic Web, knowledge graphs, and graph databases (such as Stardog – a triple store) lead me to choose that route in the book over Prolog.

Knowledge graph development has existed for decades, especially from the late 2000s when the full complement of RDF technologies became readily available. The problem is the manual encoding and maintenance of KGs was not worth the trouble for most applications. However, the emergence of LLMs changed that. Those human subject-matter experts how have an army of bright and tireless interns in the form of LLMs to assist in the monumental authoring.

This blog is about my experiments testing the place of a dinosaur (Prolog) in the modern world. For the purposes of this blog, I’m choosing to use Prolog in the interest of respect as one of the “OG” AI tools.

Before continuing, I should mention SWRL (Semantic Web Rule Language). It is a rule language for RDF of the W3C’s Semantic Web world. It is designed to be used in conjunction with RDF and OWL to enhance the expressiveness of OWL ontologies by adding rules.

I mention this because with SWRL the Semantic Web world can essentially do most of what Prolog does. SWRL/RDF/OWL tends to be more difficult to read than Prolog (cryptic XML and URL stuff). I should mention that SWRL is not a query language. It’s more like a “virtual” fact. SPARQL is the RDF equivalent to SQL for querying.

Soft-Coded Logic

Way back in 2004, I bravely and naively (stupidly) decided to create an “expert system” for SQL Server performance tuning. It encoded all I knew about that topic in a way that it could engineer novel solutions to novel (not found on Google) performance problems.

Long story short, I made good progress, but after about six months I had to put it on the backburner and focus back on my “real” work. Back then, I read of a couple of cases where researchers attempted the same thing in a different domain (biologists encoding an ecosystem). They mentioned timeframes of a couple of years to develop the KG. Although that work didn’t amount to much, it provided a very solid foundation and lessons learned. It set my path for the next decade or so, which is the subject of my book.

In addition to encoding the rules of the expert system, I needed to work out the underlying graph structure (an ontological knowledge graph and a web of cause and effect) and even build some very complicated tools. One of those tools is a language and interpreter for resolving “it depends” rules on the fly.

I immediately thought of Prolog which I had been dabbling with since the 1980s. I researched the existing implementations but they all feel short for my purposes. RDF had been around for a few years. OWL and SWRL were just coming about in that 2004 timeframe, but all things considered, I chose the crazy idea of writing my own Prolog interpreter.

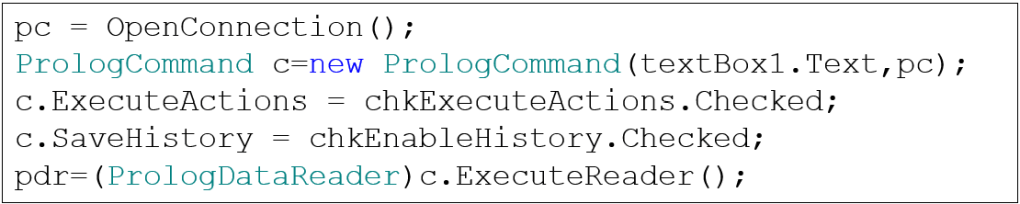

The Prolog interpreter, SCL, was written in C# and implemented as an ADO.NET provider. This is what it looked like when used in a C# application. First, we need to open a connection to a Prolog KG:

The parameter, cmbBaseURL.Text, is the name of the Prolog file. For example, c:\temp\weather.pl. But a fundamental feature is that you could specify multiple Prolog files, for example: rules1.pl+settings.pl+weather.pl

The “file name” could also be a Prolog snippet itself. For example, a client application might identify the person of interest:

rules1.pl+settings.pl+weather.pl+{person(eugene).}

Those three files will be merged into one and processed as a whole. I implemented mechanisms to ensure the files were properly registered, properly signed by the author, etc.

This is the Prolog snippet, the rules for what constitutes “Good Mail” for me:

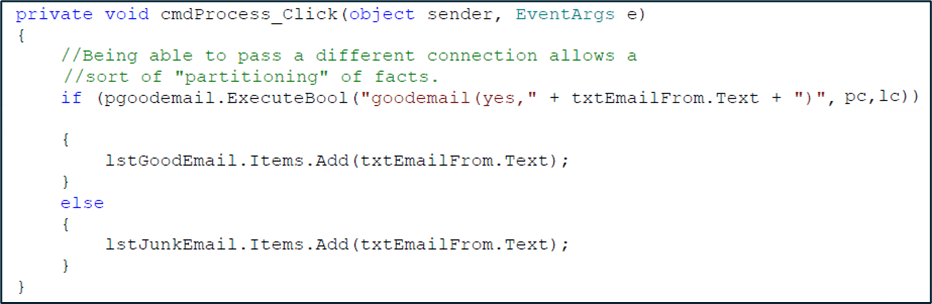

This is how the knowledge in the Prolog snippet is used in C#:

With this method, I can modify what constitutes good mail (the Prolog snippet) without needing to modify and redeploy the C# code.

Note: The SCL Execute methods could also accept a collection object of variables available for the Prolog snippet to use.

A few of the major features of SCL include:

- Highly-distributed (fragments/snippets) – Prolog would exist in snippets that could be dynamically merged at query time, not a monolithic database. That’s a modern concept that is also widely used in microservices architecture and data mesh.

- MetaFacts – Prolog facts existing as a query to another database. They were generally SQL statements to a relational database.

- MetaRules – Prolog rules existing as queries to a Data Mining model. This was primarily DMX (Data Mining eXpressions), queries to the SQL Server Analysis Services’ built-in data mining models. Around the mid-2000s, machine-learning and data science began making significant headway into the mainstream enterprise. This was a way to automatically encode rules.

- A system for “universal identifiers”. I should have used RDF for this purpose. Today I would use a unique RDF IRI/URI as Prolog element identifiers.

- Mult-threaded processing. Programs being multi-threaded even in 2004 wasn’t exactly a given. Even the venerable R language didn’t have a multi-threaded version until Revolution Analytics released its version in the late 2000s.

In a nutshell, SCL was originally intended to augment IF-THEN-ELSE code within normal programming languages, C# in particular. That way, if the rules (IF-THEN-ELSE) changed, but the procedures encoded as C# didn’t change, external Prolog could be modified without forcing changes to the C# code. Thus, “Soft-Coded Logic”.

Today, LLMs such as ChatGPT is a much easier route for building a digital SQL Server performance tuning expert. An LLM such as ChatGPT has been fed ample text about SQL Server performance tuning and is capable of substantially acting as an expert directly or just assisting in the creation of an expert system. It does seem to know quite a bit about the subject as I experimented with building an expert system with it.

I asked it how it learned this noblest of arts:

what are the sources you think you’ve been trained on for sql server performance tuning?

It’s reply:

As an AI language model, my responses are generated based on a mixture of licensed data, data created by human trainers, and publicly available data. For topics such as SQL Server performance tuning, I don’t have direct access to specific sources or proprietary databases. However, I have been trained on a diverse range of materials that include:

- Technical Documentation:

- Microsoft SQL Server official documentation and guides.

- Books Online (BOL) for SQL Server.

- Books:

- Well-known books by experts in the field, such as “SQL Server 2019 Performance Tuning” by Grant Fritchey and “SQL Server Execution Plans” by Grant Fritchey.

- “SQL Server 2017 Query Tuning & Optimization” by Benjamin Nevarez.

- “Pro SQL Server Internals” by Dmitri Korotkevitch.

- Research Papers and Articles:

- Academic research papers on database performance, indexing, and query optimization.

- Articles from reputable websites like SQLServerCentral, Database Journal, and Redgate.

- Online Resources and Tutorials:

- Blog posts and tutorials from SQL Server experts and community contributors.

- Forums such as Stack Overflow, SQLTeam, and SQL Server forums.

- Educational Platforms:

- Courses and tutorials from platforms like Coursera, Udemy, Pluralsight, and edX.

- Community Contributions:

- Best practices and performance tuning techniques shared by the SQL Server community, including MVPs and other recognized experts.

Yes, ChatGPT is probably better than a good portion of those making a living in this field. It’s breadth of virtual “experience” definitely exceeds my own. I estimate that what might have ultimately taken a year to author back in 2004/2005 would take a few weeks today with the assistance of ChatGPT as a tireless expert partner.

The intense difficulty of manually authoring such a knowledge base back then (let’s call it an AI Spring) was certainly a major factor in the failure of meeting my requirements at the time. Today, LLMs can easily generate simple Prolog or KG products. But those simple products still require diligent human scrutiny and the same battery of tests appropriate for any IT product.

It begs the question of why we would need Prolog and/or Knowledge Graphs if LLMs already contain that information (and a whole lot more). In the context of how I’m proposing the use of Prolog in this blog, Prolog is Daniel Kahneman’s Thinking Fast and Slow, System 1. It’s the application of engrained and/or learned heuristics and rules requiring split-second computation for split-second actions. System 1 rules are light, direct, and unambiguous — solutions to well-known problems.

LLMs, akin to System 2 thinking, tackle novel problems but are compute-intensive compared to processing clear rules. Human brains evolved using both methods, suggesting our AI should too. Prolog, with its rule-based logic, complements LLMs’ inferential capabilities. It appears Prolog was ahead of its time; its true potential is realized alongside advanced AI like today’s LLMs, which evolved from early perceptrons. Combining these approaches might offer a balanced, efficient AI system, leveraging both rule-based precision and adaptive inference.

Before continuing, I should mention that the SCL code is about two decades old. I don’t believe I’ve even touched it since about 2010. Last I recall, I needed to make some changes to upgrade to the newest .NET framework (I think 3.5 to 4.0), long before I gave in to the Cloud world and let my Visual Studio Pro license expire a few years ago. I have no plans to resurrect that codebase nor build a new version.

It Depends

I also used SCL to set the strength of a relationship in the expert system I was building. Some relationships are always true, such as my relationship to my parents and siblings. But most others depend on unique permutations of circumstances and context. For example, my cat belongs only to my wife when it involves changing my cat’s litter box.

catboxneedcleaning(Venus, no).

catowner(Venus, Eugene) :- catboxneedcleaning(Venus, no).

Most relationships are matters of “it depends”. If we did create a knowledge graph, relationships could be context sensitive. Here’s a good example of a simple real-world use case. When eating out, my favorite drink at lunch is a Diet Coke. But at dinner, my favorite drink might be a glass of red wine with my wife, a beer with friends, or a Diet Coke if dining with a boss or client. This is a real-world use case in that the ability for restaurants to robustly anticipate my order can help ensure a smooth experience for customers.

So Eugene will order Diet Coke, red wine, or a beer. Here is the encoding of those rules as Prolog:

businessmeal(true) :- companion(boss).

businessmeal(true) :- companion(client).

drinkorder(dietcoke) :- context(lunch), person(eugene);

context(dinner), businessmeal(true), person(eugene).

drinkorder(redwine) :- context(dinner), companion(wife), person(eugene).

drinkorder(beer) :- context(dinner), companion(friend), person(eugene).

The drinkorder rules above demonstrate the AND and OR aspects of Boolean Logic. For example, drinkorder(dietcoke) states Diet Coke is ordered if it’s lunch AND the person is Eugene. OR is represented in two ways:

- businessmeal(true) it defined with two separate rules – one if I’m dining with my boss and the other if I’m dining with a client.

- drinkorder(dietcoke) is defined in one rule, but the clauses separated by a semicolon.

While #2 looks more “efficient”, #1 makes it easier to merge multiple prolog snippets.

The Python snippet below demonstrates that if the IF-THEN-ELSE statement:

ChatGPT could readily decipher the rules:

- If the companion is the boss, then it’s a business meal.

- If the companion is a client, then it’s a business meal.

- Eugene orders a Diet Coke if it’s lunch or it’s a business meal.

- Eugene orders red wine if it’s dinner and the companion is his wife.

- Eugene orders a beer if it’s dinner and the companion is a friend.

The rules above can be merged with a Prolog snippet containing the “input variables” that are merged with the Prolog of rules:

person(eugene).

context(dinner).

companion(boss).

The merged Prolog is what is presented to ChatGPT:

person(eugene).

context(dinner).

companion(boss).

businessmeal(true) :- companion(boss).

businessmeal(true) :- companion(client)

drinkorder(dietcoke) :- context(lunch), person(eugene).

drinkorder(redwine) :- context(dinner), companion(wife),

person(eugene).

drinkorder(beer) :- context(dinner), companion(friend), person(eugene).

drinkorder(dietcoke) :- context(dinner), businessmeal(true)),

person(eugene).

Using a new ChatGPT session, I asked this question and pasted the merged Prolog above:

Based on this Prolog, what drink will Eugene order when dining with his boss? You are a Prolog interpreter: <pasted merged Prolog>

It responded:

According to the rule drinkorder(dietcoke), Eugene will order dietcoke when dining with his boss for dinner.

The beauty of the LLM is that it could infer things such as my manager is a boss without needing to explicitly state that.

Prolog is My Go To Metaphor for Deductive Reasoning

Prolog is a powerful tool for deductive reasoning. Rooted in formal logic, Prolog excels at defining relationships and rules through its concise and expressive syntax. By allowing users to specify facts and rules, Prolog systems can infer new knowledge from existing information, making logical deductions based on given premises. This capability is basically the encapsulation of the principles of deductive reasoning, where conclusions are derived logically from a set of premises.

A compelling example of Prolog’s application is in the field of medical diagnosis. Consider a doctor diagnosing a patient based on an integration of presented symptoms, information from the patient’s history, and lifestyle information. The doctor uses deductive reasoning to map symptoms to potential illnesses, implementing her vast array of medical knowledge. Prolog can model this facts and rules employed by the doctor.

For example, if a patient has a fever, cough, and difficulty breathing, the doctor might deduce the possibility of pneumonia based on the symptoms and medical guidelines. To refine this diagnosis, the doctor queries for more facts (questions to the patient and tests) to apply additional rules and either rule out or validate the initial deduction.

The doctor might ask if the patient has been exposed to anyone with pneumonia, whether there has been a recent travel history to areas with outbreaks, or if the patient has pre-existing conditions like asthma or heart disease. If the patient reports no exposure, travel, or pre-existing conditions, the doctor might consider other possible diagnoses, such as bronchitis and order a chest X-ray or blood tests to gather more information. With new information, the doctor applies it to that very sophisticated rule-base deeply etched in her brain from decades of training and experience.

Prolog’s deductive reasoning capabilities provide a robust framework for deriving accurate and meaningful conclusions from well-defined facts and rules. Its precision and clarity in expressing logical relationships suggest that Prolog should be a cornerstone for those seeking to harness the power of deductive reasoning in computational systems – without hallucinations.

ChatGPT as a Prolog Interpreter

Having used LLMs (mostly ChatGPT and Copilot) as my “paired programming” partner for over a year, it’s clear that for now, it has its strengths and weaknesses which are different from mine. That’s great since we complement each other such that I’m much more productive with my coding and writing. Bonus: It hasn’t yet made me obsolete. Like all partnerships, it takes patience and dedication to get to know each other and evolve the best way to work together.

But as my relationship with LLMs continues to evolve, it seems like the way I engage it has been evolving faster than its rate of improvement. Meaning, ChatGPT fails me a lot more than it used to. That’s probably because my relationships with ChatGPT started with inane things such as asking it to write heavy metal lyrics about Spam musubi in the style of Jean Luc Picard.

Entertaining as that might have been, I now bounce ideas off it related to the mechanics of consciousness or compose “the things a BI developer should know about vector databases”. In essence, our conversations are much deeper than before. But LLMs for the past year and a half haven’t kept up with the growing sophistication of my use cases for it.

This blog is born out of frustration with the current weaknesses of LLMs. They still frustratingly hallucinate (especially since I’m working on the cutting edge) and can’t deal well with novel ideas (resulting in answers that are square pegs pounded into round holes).

And asking an LLM questions involving a well-defined set of rules is compute overkill. Think of all the work that we programmers spent getting our code from O(n^2) to O(n) to O(1) to squeeze out all the efficiency we could from our limited hardware. It seems kind of wrong to ask an LLM to infer answers from scratch every time.

On the bright side, I do notice that asking an LLM to optimize existing code (or make it more Pythonic) works much better than giving it a manifesto of requirements and asking it to bang out the code. Unlike natural language, code, whether it’s Python, Java, SQL, or Prolog, is unambiguous. We all know it’s “easier” to edit or even improve an existing work than to come up with a crazy idea in the first place. It’s in that role that LLMs add the most value to the pool of the system’s intellect.

The big deal about LLMs is that we finally have a way for a machine to digest our unstructured, written text (from across all humanity) that is much more than just about data. It is also rules, the contexts and qualifications of real life.

Ad-Hoc Extensibility

As a BI architect and developer, most of my coding over the last few years has been Python, SQL, Cypher, RDW/OWL/SPARQL, DAX and a mix of glue code such as YAML, Curl, and PowerShell. Those are current languages I expected ChatGPT and Copilot to know. So one day, I wondered if it knew something old and obscure like Prolog.

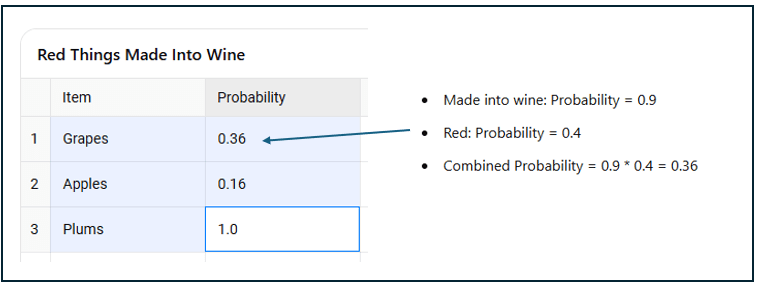

As we’ve already discussed, ChatGPT does understand Prolog. I’ve also noticed I can teach ChatGPT to extend its understanding of Prolog. For example, one of the minor features of SCL (vs standard Prolog) is that I can include a little XML snippet of supporting metadata. Below, the partial SCL snippet (the entire file is too long) states includes extra data assigning a probability to the fact just above it:

clauses

made_into(apples,sauce).

made_into(grapes,wine).

<ClauseInfo><Probability>0.9</Probability></ClauseInfo>

made_into(grapes,raisins).

made_into(apples,sauce).

made_into(grapes,wine).

<ClauseInfo><Probability>0.9</Probability></ClauseInfo>

made_into(apples,wine).

<ClauseInfo><Probability>02</Probability></ClauseInfo>

I submitted this prompt along with the entire Prolog file to ChatGPT. Remember, the ClauseInfo isn’t known as standard Prolog:

Given the following code (variant of prolog), what red things are made into wine and include the probabilities based on ClauseInfo? You must act like a prolog interpreter. Please return as a table of Item and Probability:

clauses

made_into(apples,sauce).

made_into(grapes,wine).

<ClauseInfo><Probability>0.9</Probability></ClauseInfo>

color(grapes,red)

<ClauseInfo><Probability>0.4</Probability></ClauseInfo>

made_into(@What,wine),color(red,@What)

...rest of prolog file...

ChatGPT correctly returned the list of red things that are made into wine and probabilities of being made into wine:

In the example, LLMs have the ability to go beyond responding with syntax errors when things are ambiguous — which is in reality, most of the time.

Reading Minds

Of course, rules at times can be even more sensitive to an organization than even data. It’s not just what we know, but how we apply what we know. Knowing what is going on in our mind, how we interpret data, is more strategically valuable than knowing what data we’re aware of.

If I assume OpenAI or another LLM vendor does not keep a record of prompts, this is kind of OK. But I’d need to trust they will not be responsible for a data breach, they don’t quietly change the rules retroactively, or the company is prone to corporate espionage. Conversations between ChatGPT and me is much richer than keyword searches and clicks known to Google.

Grammatically Forgiving Interface

Using Prolog rules can be beneficial for ensuring precision and clarity, especially for complex logical relationships where mistakes enabled by designed flexibility cannot be tolerated. It reduces the chances of misinterpretation compared to natural language, which can be ambiguous. However, it requires familiarity with Prolog syntax, which really isn’t all that bad. But any syntax isn’t as easy to use as the grammatically forgiving interface of LLMs.

Providing rules in Prolog is particularly useful when precision and formal logical structure are paramount, while natural language can be more effective for conveying broader context and nuances.

So, Does Prolog Have a Place in the LLM Era?

Redundancy in programming languages never seemed to be an issue. Think of Java and C# for enterprise software or R and Python (well, the pandas, numpy, matplotlib, and scikit aspects of Python) for machine learning. So nothing stops Prolog from co-existing in this modern Semantic Web world of RDF, OWL, SPARQL, and SWRL.

However, Prolog could leverage RDF as the foundation for global and unique identification of objects. For example, here is a simple RDF with recognized unique identifiers stating Joe Biden is the President of the United States:

@prefix ex: http://example.org/ .

@prefix dbo: http://dbpedia.org/ontology/ .

@prefix dbr: http://dbpedia.org/resource/ .

dbr:Joe_Biden dbo:presidentOf dbr:United_States .

Here is a Prolog snippet using the RDF unique identifiers:

presidentOf('http://dbpedia.org/resource#Joe_Biden', 'http://dbpedia.org/resource#United_States').

Using the RDF unique IDs isn’t as tidy and clear as presidentOf(Joe_Biden, United_States), but it does provide a link into the Semantic Web’s RDF world, leveraging a well-established mechanism for globally recognizing objects.

Prolog in a Mixture of Agents or RAG Implementation

In the context of a mixture of agents or Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) AI implementation, Prolog can play a crucial role as a sleek reasoning agent. Since Prolog’s strength lies in its ability to perform logical reasoning and complex queries, it makes an ideal candidate for tasks requiring intricate rule evaluation and decision-making. Modern Prolog implementations can be integrated into a multi-agent system where different agents perform specialized tasks. For instance, while LLMs handle natural language understanding and generation, Prolog can manage well-defined logical inferences, rule-based decision-making, and query optimization.

A RAG system combines the generative capabilities of LLMs with retrieval mechanisms to produce more accurate and contextually relevant responses. In such systems, Prolog can serve as the engine for retrieving and reasoning over structured data, ensuring that the generated content aligns with complex business rules or domain-specific logic. The scalability improvements in modern Prolog implementations, such as multi-threading in SWI-Prolog, make it feasible to incorporate Prolog into large-scale, high-performance applications.

Integrating Prolog into a mixture of agents or RAG implementation involves leveraging its logical reasoning capabilities alongside the data processing and language generation strengths of other technologies. This hybrid approach can enhance the overall system’s efficiency and accuracy, enabling it to tackle a wide range of complex tasks. By utilizing Prolog’s advanced features and scalable implementations, developers can create robust systems that effectively combine the best of logical reasoning and generative AI.

Scaling Prolog: Challenges and Modern Implementations

Scaling Prolog poses unique challenges due to its inherent characteristics. Unlike highly scalable databases processed in a MapReduce framework, Prolog KBs can’t be partitioned into chunks that are independently processed then the independent results merged together.

Prolog is data (facts) and code (rules-chains of Boolean expressions). Further complicating it is that the data is code and the code is data. A simple fact, such as likes(eugene, pizza), could be thought of as a one-term rule in itself.

Prolog’s execution involves exploring multiple paths through a search space, often using recursion extensively, which can result in deep and complex call stacks. These factors make it difficult to parallelize Prolog computations efficiently. Additionally, Prolog’s dynamic nature, where the outcome of queries can change with updates to the knowledge base, complicates caching and necessitates frequent re-evaluation of queries.

Despite these challenges, there are a few modern implementations of Prolog have introduced various features to enhance performance and scalability. Here are a couple of examples, I’ve looked into, but keep in mind that this blog is about an idea. Meaning, I’ve only experimented with these versions:

- SWI-Prolog, for example, supports multi-threading, allowing significant parallel execution. It has demonstrated an 80x speedup on a 128-core system, making it suitable for CPU-intensive server tasks. SWI-Prolog is versatile and used in applications ranging from natural language processing to linked data processing.

- Ciao Prolog is another modern implementation designed for extensibility and modularity. It supports multiple paradigms, including meta-programming and concurrency, and includes features like separate and incremental compilation to manage large codebases efficiently.

Estimating the Difference in Compute Resources for Prolog vs. Text Processing

For the computational tasks we just discussed, logical reasoning and natural language processing, there is a difference in computational resource requirements. Prolog, a logic programming language, excels in rule-based reasoning and efficient query evaluation. Conversely, LLMs require significantly more computational power due to their complexity. This comparison highlights the resource efficiency of Prolog for specific tasks versus the substantial demands of LLMs.

It’s very difficult to gauge the difference of computation resources between LLMs and a Prolog interpreter. First, keep in mind that the primary idea is accuracy of interpretation since Prolog rules are explicit. Thus, provided the Prolog is limited to relatively light snippets of rules, it should be fairly obvious that querying from a Prolog database should be magnitudes more efficient as well.

Prolog using a Prolog Interpreter:

- Efficiency: Prolog is designed for efficient logical queries and rule-based reasoning. Simple rules are evaluated quickly using basic operations such as unification and backtracking.

- Resource Usage: Minimal CPU and memory resources are required. Evaluating a few logical rules is computationally inexpensive, making it highly efficient for specific tasks.

Text Processing with LLM:

- Complexity: Processing natural language text with an LLM involves parsing, understanding context, and generating responses. This requires complex neural network operations and significant computational power.

- Resource Usage: Substantial resources are needed, including high CPU, GPU usage, and large amounts of memory. The resource demands can be several orders of magnitude higher compared to Prolog.

Considering the comparisons above, I would think submitting the same Prolog (or the natural language equivalent of the Prolog) would be much more intense on an LLM versus scaled-out Prolog services.

Prolog Execution: Considered as a baseline (1x).

- Text Processing with LLM: Can require approximately 10x to 100x more compute resources due to the complexity of natural language understanding and generation.

Prolog’s efficiency in handling logical rules contrasts sharply with the substantial computational demands of processing natural language with LLMs. While Prolog should incur relatively minimal overhead, LLMs require significantly more resources, making Prolog an efficient choice for specific rule-based tasks compared to the resource-intensive nature of LLMs.

Prompt for LLM Prolog Authoring Assistance

The tremendous difficulty of authoring expert system rules, whether in Prolog or with the Semantic Web specifications, was a huge impediment to achieving AI through that path. The current LLM AI era evolved along a different trajectory that began with the perceptron, progressing through neural networks, backpropagation, and multi-layered neural networks, to CNNs/RNNs, and beyond.

With both approaches now in existence, users can leverage ChatGPT to assist with authoring Prolog to reflect custom rules, even without prior knowledge. This is a sample prompt I created that demonstrates how a user who doesn’t know Prolog can engage ChatGPT’s assistance:

I need you to convert my request into Prolog. I don't know Prolog, so please also explain the prolog you generate in simple terms. And include examples of how to query it. Before actually creating the Prolog, please ask me questions for information you need.

My wake-up alarm needs to automatically set. Assume you have access to my outlook calendar.

On weekdays I normally need to awake at 7am. That is if I need go to the office and I didn't get home late from work. if I can work from home, I'd like to awaken at 6am - that way I can go to the gym first thing in the morning. Of course, if I have a meeting scheduled before 8am, set my alarm for an hour before that first meeting. On weekends, set my alarm to 9am unless I have some sort of appointment before then.

The conversation is too much for this already terribly long blog. Try it yourself, it’s kind of entertaining. I posted my prompt and the Prolog it generated on the book’s github site.

ChatGPT first asked me questions such as “What is considered ‘getting home late’?” I answered its questions – apparently to its satisfaction as it proceeded to create the Prolog. It also explained the Prolog is clear and methodical terms so I could test that we’re completely on the same page. Finally, it provided a test script of queries.

The generated Prolog is code and should be treated like code. As such, it should be subject to governance like any other software: version/source control, testing with test scripts, reviews for optimization and potential vulnerabilities, encryption, signing, and monitoring usage. I imagine the Prolog being deployed in a microservices architecture. Each Prolog snippet is indeed a function.

Security, Sovereignty, and the Placement of Strategic Knowledge

Note: This topic was added on February 18, 2026. When I originally wrote this blog back in August 2024, the point of this blog was just to introduce the notion of implementing Prolog in the LLM era. But I realize I need to explicitly state the advantage of Prolog in terms of reducing exposure of sensitive rules (not just data) to LLMs. I had only implied this previously, assuming this is out of scope for this blog.

Since a primary theme of this post is that we can use LLMs to author Prolog (at least drafts), we need to address sending prompts describing that sensitive information. Please see this topic addressed in Should We Use a Private LLM?

One aspect of the Prolog–LLM partnership that must be addressed—particularly in enterprise settings—is not just epistemological but architectural: where sensitive knowledge should live.

In the framework of Enterprise Intelligence, LLMs are extraordinary translators and inferential engines. They excel at synthesizing unstructured knowledge, mapping between modalities, and assisting with novel reasoning. But their very strength—being trained on vast external corpora and often accessed through externally hosted endpoints—introduces a governance tension when applied inside an enterprise.

Even if prompts do not contain customer PII, they often carry something at least equally sensitive: strategy, planning intent, operating assumptions, and internal decision logic. In an enterprise architecture, those elements are crown-jewel intellectual property—closer to executive thought than transactional data. The development of such structures goes beyond “what I know” to “how I think”.

Submitting such prompts to an externally controlled LLM—even under contractual assurances of non-retention—introduces a dependency on policies that may evolve over time. From an architectural standpoint, this creates an unstable trust boundary, one that sits outside the enterprise’s direct governance.

Symbolic systems such as Prolog (and knowledge graphs) offer a complementary advantage here. So, explicitly stated, because Prolog knowledge bases are explicitly authored, versioned, and deployed like code, they inherit the full security and governance model of traditional enterprise systems:

- They reside within controlled infrastructure.

- Access can be governed through role-based controls.

- Changes are auditable and reversible.

- Sensitive logic can be segmented and compartmentalized.

- Knowledge can be revoked without retraining a model.

In this sense, Prolog is not merely a deductive engine—it is also a sovereign knowledge store.

This does not diminish the role of LLMs. Rather, it clarifies it: LLM as the know-it-all friend who knows a lot about a lot of things and can answer most common sense questions involving commonly known data, while Prolog holds the private intelligence of logical formats such as those of strategies, business rules.

A balanced enterprise architecture might position:

- Prolog (or rule/KG systems) as the secure vault of plans, policies, and deterministic logic.

- LLMs as translators, orchestrators, and hypothesis generators—operating on the edge of that vault rather than embodying it.

In such a design, LLMs act as architectural mortar: converting between natural language, code, graphs, and rules—but not serving as the permanent repository of strategic knowledge itself. The point of this blog is not to choose between symbolic systems and LLMs, but to place each where its strengths align with both cognitive function and governance reality.

Since a primary theme of this post is that we can use LLMs to author Prolog (at least drafts), we need to address sending prompts describing that sensitive information. Please see this topic addressed in Should We Use a Private LLM?

Conclusion

LLMs, broad and fuzzy, are complemented by the logical precision of Prolog. Throughout this blog, we’ve explored how these two technologies can work together to create more robust AI systems. Assuming AI isn’t at the AGI level:

- Prolog’s strength lies in its ability to resolve queries or sub-queries with well-defined logic, making it ideal for tasks requiring clear rules. Query resolution should be substantially faster and less compute-intense, which should result in lower AI costs.

- LLMs can step in as a backup for logical processing when appropriate Prolog rules are absent.

- LLMs can assist in the authoring of Prolog, enhancing the development process. This democratizes AI to that majority of people who have never written a book, article, or even a blog, but have unique knowledge and skills that add value to our common knowledge.

By leveraging the strengths of both LLMs and Prolog, we can achieve a balanced approach to AI, combining the structured rule-based logic of Prolog with the versatile inferential capabilities of LLMs.

Earlier I mentioned that perhaps Prolog was ahead of its time, needing to wait for LLMs to mature. This parallels the evolution of System 1 and System 2 in the brain. Loosely speaking, let’s say System 1 resembles the “primitive limbic system” that predates the advanced neocortex. Today, our advanced cognition allows us to train ourselves in to advanced “second nature” skills like playing musical instruments, athletics, and high-knowledge fields such as medicine, law, and programming. In a similar way, Prolog’s rule-based logic complements the sophisticated inference capabilities of modern LLMs.

Whether or not you’re able to apply what this blog series presents, it’s incredibly important for us to further develop our insight into how we think. This can become more and more difficult as AI such as LLMs improve and become more prevalent and critical thinking quickly atrophies. Similar to how a sport or martial art helps you to learn about movement or how learning to play a musical instrument elevates the engagement of your sense of hearing to higher levels, composing Prolog will hone your sense of systems thinking. We are sentient and sapient creatures.

I hope that you will be fortunate enough to find yourself in a position where you can get your hands very dirty applying Prolog or a similar technology (such as knowledge graphs) in this era of LLMs.

Part 2 of this series dives a little deeper into what I had in mind for SCL. In a phrase: Prolog AI Agents.