Previously in Part 1 of Prolog’s Role in the LLM Era:

- I made a case for partnering fuzzy LLMs with deterministic rules.

- This blog is really “Appendix C” of my book, Enterprise Intelligence.

- Presented a simple introduction to Prolog.

- Introduced my Prolog variant named SCL.

- Discuss Prolog as an alternative RDF-based Knowledge Graphs.

- Discuss Prolog processed with a Prolog engine as well as Prolog as unambiguous parts of an LLM prompt.

In this episode, I discuss the bigger plans I had for SCL back in 2004-2010. The excruciating difficulty with authoring and maintaining substantial Prolog Knowledge Bases (KB) was too much of a hurdle back then. However, as it is with the Semantic Web (RDF/OWL were also relatively new to the stage back in the mid-2000s) today, human subject-matter experts (SME) partnering with LLMs to author knowledge graphs (whether RDF or not) can tremendously mitigate the difficulty.

Similarly, LLMs can work symbiotically with Prolog to encode a “golden copy” of the rules after rounds of iterative refinement with both human intelligence and LLMs. By “golden copy,” I mean a perfected version of the rules, similar to how creators refine a book, a song, or a scene until they achieve the ideal “take” and finalize it for production. In this context, Prolog rules can be considered a cache for LLMs – a set of vetted, reliable rules that don’t need to be recomputed from scratch for every query.

The advantage that encoding with Prolog has over fine-tuning a foundation LLM (continuing the “neural network training” with more data—private, updated, or specialized) is that Prolog maintains its transparency and traceability. Prolog rules remain clear and distinct, unlike the way water, coffee, sugar, chocolate, and cream mix into an indistinguishable mocha.

There is a knowledge dichotomy that begins with the fuzziness of LLM, founded upon the fuzziness and associated complexity of the world we live in. Consequently, our sentience is fuzzy (let’s call it robust), our language is fuzzy (let’s call it flexible), and the results of our processes are fuzzy (sometimes things don’t turn out as expected or as we had hoped). But all that fuzziness is a mixture of repetitive cycles innately defined by rules, slowly evolving from the interaction of those cycles.

What I Had in Mind for SCL

I’d like to discuss a little about the bigger plans I had for SCL back in 2004, the idea of “separation of logic and procedure”. My plan is like a cousin of how we deploy machine learning models to offer best guesses and/or make decisions. The difference is that ML models are trained on massive volumes mostly structured of data in a similar way that LLMs are trained on massive amounts of unstructured data.

Back in 2004 I thought it was a trillion-dollar idea … hahaha. The core of the idea is no longer novel. So much has happened in the last 20 years! The maturity of the W3C’s Semantic Web specifications and LLMs mostly took care of that. Keep in mind that when I was pondering this idea, we were well over a decade away from even bad LLMs. I’m discussing this old idea today because LLMs didn’t really make the idea obsolete. It represents the other side of the coin – fuzzy/trained on one side (LLM/ML), deterministic/crafted on the other side (Prolog or Semantic Web).

Separation of Logic and Procedure

The idea was that if logic could be decoupled from procedure (that is, the Boolean logic of IF-THEN-ELSE statements of code), users (human, AI, or any other kind of agent) could customize the rules that would trigger the branch of the IF-THEN-ELSE statement. What’s so great about that? As we saw in my example of my preferred drinks back in Part 1, rules are different under different contexts. And contexts can be defined in a mindboggling number of ways in many more dimensions you can imagine.

In a nutshell, the details involved with decisions (IF-THEN-ELSE is about decision making) change over context and time. But set of decisions we make remain more consistent. For example, throughout all lives, we choose a job, a place to live, who to live with, a mode of transportation to and from work, and who will do the dishes.

Current conditions could be retrieved from databases using the MetaFacts feature. The rules and predictions of ML models were incorporated by the MetaRule feature that I mentioned earlier in Part 1. Current conditions, the rules from the ML models, and custom Prolog rules would be readily merged at query-time.

Hierarchy of Prolog AI Agents

The main idea is that people and businesses could author Prolog to reflect their rules and the ability to independently update those rules. The complexity of the Prolog would range from the simple rules we’ve played with in this blog to fully-fledged expert systems like the one I developed for SQL Server performance tuning.

There would be levels of Prolog literacy required. That doesn’t just mean knowing the Prolog syntax, but like any coding, there is a high-end skill in translating what you think/feel/prefer into code. I think a workable level of Prolog skill is as relatively accessible to a wide audience as SQL or Python – it’s not C++. There is a hierarchy of skill levels:

- Expert – Domain SMEs and Prolog experts developing Prolog of book-level scope and complexity. High-end Prolog that is really a code version of a how-to book. The population of folks at this level would be similar to the number of people who’ve authored books. LLMs are employed as an army of helpers for fact-checking, streamlining, etc. LLMs at the time of writing certainly cannot author Prolog at his level without humans as the leads.

- Intermediate – Prolog enthusiasts and practitioners who have moved beyond basic usage and are capable of creating moderately complex Prolog systems. They can author rules and logic to reflect more sophisticated business or personal needs without requiring the depth of knowledge needed for expert-level systems. Kind of like developers who can write complicated Python scripts, but not design an entire system.

- Novice – This is the method of cut/paste from Stackoverflow or Reddit and customize. This is how the vast majority of Prolog would be generated. The use cases are easy enough and minimally consequences where an LLM could be trusted to write the Prolog from just a request.

- None – This level is just about adopting what someone else is doing or accepting defaults. The user need never see Prolog.

Note that even for an expert with Prolog, for the bulk of the expert’s use cases will be novice or none. In terms of sheer number, most things in our life simple decisions not requiring a PhD to work through.

Back in 2004, I thought that the effort required for writing a reasonably complicated expert system for a domain would be within the same magnitude of difficulty as writing a book. For example, authoring Prolog for SQL Server performance tuning would be roughly as difficult as writing a book on SQL Server Performance Tuning. It really depends on the domain, but I think the error margin for this thought is within a reasonable range (more of less difficult by 2x to 3x-ish, as opposed to 10x or 100x).

I imagined that this book-level Prolog would be authored by firms with knowledge of Prolog paired with SME “authors”. That’s similar to a publisher working today with authors outputting professional-level books.

Additionally, current book publishers output various formats of the book – ex. Kindle, PDF, hardback, paperback, audio. A Prolog version could be another format. For AI or other software agents, Prolog is an easily digestible format – direct.

As some books don’t make good Kindle or audio versions, not all books will be candidates for Prolog. This would apply more to the technical how-to books. The Prolog could be sold like a book or it could be implemented in a vast repository of Prolog supplying possible rules to human, AI, or API consumers.

However, unlike a book, the expert system would be more prone to updates much more frequent than a book with a new edition every few years. And, an author of a book can depend on an expectation of prerequisite skill, whereas that prerequisite skill for a Prolog KB spelled out as well — in other words, you need to spell out all the background knowledge that is expected of a reasonably educated person.

So the advice and information that currently lies with book or magazine publishers and media dishing out advice (YouTube videos, blogs, articles, apps) would publish the same information in the form of Prolog snippets. That’s no longer a worthy idea since LLMs can automatically derive expert advice from the natural language content of those videos, blogs, articles, etc. For example, it’s routine to feed an entire article to ChatGPT and ask it questions about it, of course, in cooperation with the LLMs trained knowledge.

Beyond the “advice” authored by what is a relatively small population of experts who develop those articles and books, everyday consumers and armies of knowledge workers could encode very simple Prolog snippets expressing their custom facts and rules. For this audience, the level of Prolog is simple, so it could be developed through a relatively easy app or directly as easy Prolog.

The many Prolog snippets could be implemented in a manner similar to microservices. Each is really a function. Software systems would access the Prolog snippets, mix and match them, and compute answers to queries. The authors and their Prolog snippets could offer a price for access and paid accordingly. The incentive for payment to Prolog authors would ensure honest, high-quality, and intelligent Prolog.

Think of the difference between the Prolog authoring process by experts (1) versus novices and none (3,4) like the difference between CPUs and GPUs, respectively. CPUs are great for computing a complicated tasks serially, while GPUs are great for computing a large number of simple tasks in parallel.

Today, OpenAI’s GPT Store is an example of an idea that currently resembles this vision. The GPT Store allows users to create and fine-tune custom versions of ChatGPT for specific tasks or topics. These custom GPTs can be tailored without coding skills, enabling anyone to design AI that fits their unique needs. This is very much like with the SCL concept, where logic (the rules and knowledge) is separate from the procedural code (the actions and responses).

But custom GPTs are still LLMs that deny us direct control over its output. More akin to my idea of SCL are the off-the-shelf ontologies such as the Financial Industry Business Ontology (FIBO). Such ontologies intended for semantic web knowledge graphs encoded with semantic web standards. FIBO provides a comprehensive, standardized framework for financial industry concepts, much like how SCL aimed to provide a customizable and adaptable rule set.

Artifacts

Artifacts in the context of LLMs refer to reusable pieces of logic, code, or data that can be applied to various tasks and scenarios. These artifacts can be created, used, and saved for future use, enhancing efficiency and consistency in handling similar tasks.

Python artifacts are the most common type that come up in my work with ChatGPT. It often goes unnoticed. For example, I submitted a CSV file of data to ChatGPT and asked:

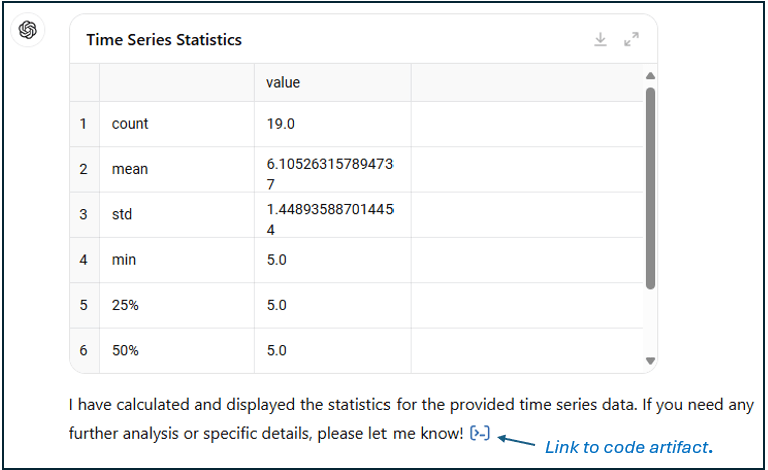

Could you provide statistics on the attached time series?

It responded with a table of the statistics and a little explanation, and a blue icon.

One of the notorious quirks of LLMs had been that it doesn’t do math well. An LLM alone can’t perform math reliably. But it can engage a helper within a RAG process. Notice towards the lower-right, the blue icon is a link to the little Python program below that ChatGPT created:

Like humans, LLMs might struggle with math calculations, but it still knows the procedure – which it can encode.

If providing standard statistics is something I will do very often, it would be smart of me to use the concise Python artifact ChatGPT created rather than to ask ChatGPT each time – whereby it computes from scratch. It will save on the OpenAI bill and ensure the calculation is performed the same way each time (should ChatGPT decide to do something else). I believe at the time of writing, OpenAI is thinking about caching mechanisms – one of which could be caching these artifacts.

Prolog Artifacts

As I’ve presented Prolog in this blog, it could be thought of as another class of artifacts. It’s a light piece of unambiguous code (not a fully-fledged SaaS application). Whether authored by people, LLMs, or in collaboration, Prolog snippets can be re-used in the same manner as Python artifacts.

At some point, the vendors of the major LLMs (OpenAI, Google, Facebook, Tesla, etc.) will incorporate processing encoded rules with a logic engine as a first-class agentic capability. That’s what we humans do when we’re pretty sure we now understand the rules and so it can now be set in stone, encoded for automation. It’s only when we don’t completely understand how something works that we force those versatile humans to continue doing the work.

- Prolog (or any code) is good when the rules are clear.

- LLMs are good for when inference is complex and fuzzy.

- Our aggregate intelligence (across all of we people) have served us well in creating novel solutions to novel problems. At least for now, all LLMs need to say, “Humans taught me everything I know.”

It’s not that LLMs can’t eventually perform at all to the reliability and specificity of Prolog or can’t do any creative and original thinking. It’s still prone to hallucination and it currently isn’t better at thinking anywhere near the cutting edge than we are.

As long as the encoded rules are relatively light, processing those rules should be dramatically less compute-intensive than processing a prompt through a trillion-plus parameter LLM. Partitioning AI tasks between the System 1 Prolog and System 2 LLM won’t be great for Nvidia, but it helps to move away from the cargo cult mentality of relying solely on ever-growing capabilities that may or may not come soon enough or ever. Until we achieve AGI (Artificial General Intelligence), let people do what they do best, let LLMs do what they do best, and let Prolog do what it does best.

Where Do You Get the Rules?

During my first demo of SCL (2005?), one of the attendees mentioned having worked on Prolog-based expert systems back in the early 1990s. He mentioned that (as I’ve mentioned), encoding the rules is the hard part. “Where do you get the rules?”, he asked. Well, from cross-functional teams of SMEs, managers, and programmers, just like any other software project.

I knew that was a terrible answer. Software can be developed because we have well-defined rules. We can encode anything as long as we know the rules, as Dave Portnoy might say. But what if the rules are in flux? For example, evolving business drivers, the whims of customers, or economic conditions.

Well, automatically deriving rules is what ML is all about. Assuming we capture the right data, that possibly massive volume of data can be cooked down into a handful or rules. Essentially, when we develop and deploy ML models, we’re deploying rules for automatically making some sort of decision.

Back then, my platform for ML was the “data mining” component of SQL Server Analysis Services 2005 (SSAS). It features a handful of simple but versatile algorithms such as decision trees, association rules, and clustering. In the context of Prolog, we could define ML models as the way to automatically derive facts and rules from data.

MetaFacts

MetaFacts are an extension of Prolog I implemented in SCL. It specifies queries that can create facts and/or rules on the fly from external sources such as databases or deployed ML models.

This example generates virtual facts for the predicted car model of customers:

The query is DMX, the query language of the data mining models built in SSAS (note MDX is the language for SSAS cubes). Note the query parts beginning with PROLOG? Those are instructions for replacing it with a Prolog call to itself.

The result would be something like: predicted_car_model(eugene, Sedan).

MetaRules

A MetaRule is similar to a MetaFact. But a MetaRule returns the logic instead of a fact. For example, the CarModelPrediction SSAS data mining model contains a list of rules for determining the car model for customers based on age and occupation. The following could be retrieved with a metadata query to a decision tree data mining model:

predicted_car_model(@custid,Sedan) :- occupation(engineer), @age>50.

<ClauseInfo>

<Probability>0.4</Probability>

<Confidence>0.6</Confidence>

<Support>439</Support>

</ClauseInfo>

predicted_car_model(@custid,Sports) :- occupation(lawyer), @age>30 && @age|50.

<ClauseInfo>

<Probability>0.7</Probability>

<Confidence>0.8</Confidence>

<Support>345</Support>

</ClauseInfo>

predicted_car_model(@custid,Truck) :- occupation(farmer), @age>20.

<ClauseInfo>

<Probability>0.9</Probability>

<Confidence>0.95</Confidence>

<Support>248</Support>

</ClauseInfo>

Note that I had added an extension to SCL enabling the encoding of metadata for each fact and rule. That metadata is enclosed within an XML snippet. For example, for the three rules extracted from a decision tree, we retrieved the probability, confidence, and support of the respective node of the decision tree.

Today, instead of querying a data mining model from good old SSAS 2005, we can use serialized machine learning models stored in files, such as a pickle file, to obtain the rules. This allows for more flexibility and ease of integration with various systems. By saving a trained model to a pickle file, we can load and interrogate it to extract the rules and their associated metadata, much like the MetaRule concept described previously.

Lastly, the processed MetaFacts and MetaRules could be cached in Prolog form and inserted or imported into the host Prolog as needed. That should be much faster since it’s not a database or API query at risk of taking longer.

My book’s github site includes an example of creating and retrieving the rules we just discussed.

Relationship Probability – It Depends

As discussed in Part 1, the existence of most relationships aren’t certain. For example, many people have been surprised to find out someone they thought was their parent isn’t true. However, the validity or invalidity of most relationships aren’t as shocking. The example below demonstrates that a cough doesn’t necessarily lead to a diagnosis of a common cold, even though that is one of the possibilities.

The correct diagnosis depends on the quality of symptoms, patient history, and present circumstances. The rules can be complicated and evolving. In this case, the possibility for a common cold when presented with a cough could be guessed using the following Prolog:

% Define a rule to diagnose common cold based on factors

diagnose(Patient, 'common_cold') :-

has_symptom(Patient, 'cough'),

age(Patient, Age), Age < 50,

smoking_status(Patient, 'non_smoker'),

duration(Patient, Duration), Duration < 10.

Given a set of symptoms, patient history, etc., Prolog snippets could be processed. As new information is discovered, the Prolog could be independently updated.

That Prolog snippet above is around the level of logical complication I’m talking about for this use case. It’s simple enough where today’s LLMs could often compose the Prolog from a user’s description. At the very least, today’s LLMs could write a first draft and review your changes as the know-it-all that it is.

Wide Breadth of Prolog From “the Masses”

In my book, I discuss how the legions of knowledge workers who have never published a book, article, or hosts a viral social media channel doesn’t have much opportunity to contribute to LLMs. Almost all of their unique highly specific knowledge exists only in their brains. It’s just the relatively tiny proportion of the population – intellectuals, politicians, and highly ambitious – who produce tangible artifacts of their knowledge for LLM processing to consume.

What’s worse is that most of what we employ in enterprise analytics related to the vast majority of people are inferences based on statistical machine learning models. Usually, the conclusions we draw from a study are based on a “majority”. For example, whenever someone starts a sentence like, “Young people today are interested in …”, that’s just a generalized guess.

The value is if we cater to what it seems the majority needs, we target the biggest population and can benefit from streamlining our product line and production processes. Without thinking too much, that makes sense. For example, 51% of people like chocolate and the rest are split among twenty other groups. It’s makes sense to cater to only to the chocolate majority – economies of scale with our chocolate vendors, simplified production line, marketing and distribution. Besides, chocolate is probably #2 or #3 for the majority of the remaining 49% – they’ll get used to only chocolate.

The ability for “the masses” to express their desires in an unambiguous, incredibly robust, and relatively easy manner, enables them to through their voices into the LLM amalgamation of knowledge. Remember, all of us in most ways of the practically infinite ways we might slice and dice the population will usually find ourselves in some perspective of the masses.

Their individually tiny voices from one point of view or another might aggregate in very robust and surprising manners through the transformer architecture processing of LLMs. It beats finding an understanding of unheard members of the population through the statistical manipulation of data that has been stripped of the vast majority of its context.

Lastly, note that the LLMs remove much of the friction that made the notion of individually-crafted Prolog just a crazy idea. Today, LLMs remove much communication friction between people and anything technical. LLMs are “good enough” today where it can assist non-technical people in expressing and updating their wishes.

Yeah, yeah … most people will still won’t take the trouble.

Conclusion

In this episode, I made the case for combining fuzzy LLMs with deterministic Prolog rules to achieve more robust and transparent decision-making systems. By introducing Prolog and my variant SCL, I’ve shown how Prolog can serve as a transparent, traceable alternative to fine-tuning LLMs with additional data. The complexity of authoring Prolog rules is mitigated by leveraging the symbiotic relationship between LLMs and Prolog, creating a “golden copy” of rules refined through human and AI collaboration.

Moreover, Prolog’s clear and distinct rules provide a reliable foundation, unlike the blended nature of neural network models. This separation of logic and procedure ensures that our decisions, though influenced by ever-changing details, remain consistent and well-defined.

As technology evolves, the hybrid approach of using Prolog for deterministic tasks and LLMs for more complex, flexible inferences will continue to optimize efficiency and reliability. This partnership not only enhances our ability to automate decision-making but also underscores the enduring value of clear, well-crafted rules in an increasingly data-driven world.

While LLMs handle the complexity and fuzziness of human language and thought, Prolog offers a stable, rule-based framework that ensures consistency and traceability. This combination leverages the strengths of both approaches, paving the way for more sophisticated and reliable AI systems.

There is something about this approach, particularly simple Prolog snippets, that is closer to genuine democratization of information than LLMs requiring prodigious resources to develop. A big theme of my book, Enterprise Intelligence, is to mine a simple level of knowledge from the broad legions of knowledge workers throughout an enterprise – those knowledge workers who have vital understanding but have never published an article, blog, book, or YouTube presentation.

In Part 3, we’ll play a bit with Prolog and do a couple of exercises using Prolog with LLMs.

This blog is Chapter VII.2 of my virtual book, The Assemblage of Artificial Intelligence.