Previously on Prolog’s Role in the LLM Era, I discussed:

- Making a case for partnering fuzzy LLMs with deterministic rules.

- Positioning this blog as what is really “Appendix C” of my book, Enterprise Intelligence.

- Prolog as an alternative RDF-based Knowledge Graphs.

- Prolog processed with a Prolog engine as well as Prolog as unambiguous parts of an LLM prompt.

- The big picture use case for Prolog in partnership with large language models (LLM).

- How authoring Prolog with assistance from LLMs opens the door to that vast majority of people whose voices don’t contribute to the commercial LLMs.

- The basics for working with Prolog in a Python environment with SWI-Prolog and pyswip.

- A few implementation techniques, for example, using LLMs to generate a short description from which we create an embedding and add to a vector database.

In this episode, we’ll explore the relationship between Prolog and Machine Learning (ML). That is, ML models as an automated way of encoding probabilistic rules. ML models are in a “Goldilocks” middle position – not as fuzzy and broad as LLMs but not as deterministic and specific as code (whether Prolog, Python, Java, or even SQL).

By incorporating machine learning-derived rules into Prolog, we can streamline the process of knowledge encoding, making it more feasible to create expert systems that accurately reflect real-world scenarios and behaviors without relying entirely on manual rule creation. This blend of machine learning and logic programming not only reduces the burden on human experts but also allows for more dynamic and adaptable systems that can evolve with new data and insights.

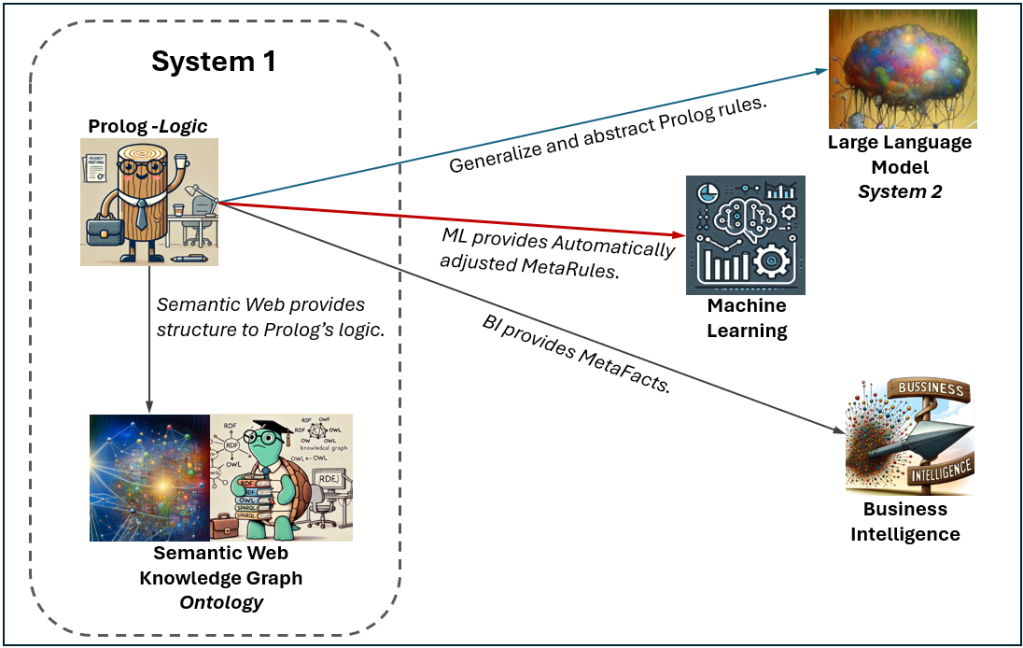

The figure below shows how Prolog works with various aspects of AI. In the first three episodes, we looked at how Prolog interacts with LLMs. In this episode, we’ll explore Prolog and its relationship to ML (red line):

I do recommend reading Part 1 through Part 3 first.

Machine Learning Algorithms

Of course, LLMs are ML models, but roughly speaking, they fall in the robust and fuzzy category of neural networks. A sampling of the interpretable, robust, but not quite as fuzzy ML algorithms include:

- Decision Trees are used for both classification and regression tasks. They work by splitting the data into subsets based on the value of input features, creating a tree-like model of decisions. For example, predicting whether a customer will buy a product based on their demographic information.

- Association Rules are used to discover interesting relationships, or “associations,” between variables in large datasets, often used in market basket analysis. For, determining which items are frequently bought together in a supermarket.

- Clustering is used for grouping a set of objects in such a way that objects in the same group (or cluster) are more similar to each other than to those in other groups. It is often used in exploratory data analysis. For example, segmenting customers into distinct groups based on purchasing behavior.

- Linear Regression is used to model the relationship between a dependent variable and one or more independent variables. It is often used for predicting continuous values. For example, predicting house prices based on features like size, location, and number of bedrooms.

- Logistic Regression is used for binary classification problems. It estimates the probability that a given input point belongs to a certain class. For example, predicting whether a customer will default on a loan (yes or no).

Most of the ML algorithms can be utilized in Python through the scikit-learn (sklearn) library. For association rules, the mlxtend library provides implementations of the Apriori algorithm and tools for generating association rules from itemsets.

In the context of the relationship between Prolog and various ML models, an important distinction is that some ML algorithms create models that are more “symbolic” versus those that are more “algebraic.” Symbolic models, such as clustering, association rules, and decision trees, operate by explicitly manipulating symbols and rules. They produce results that can be easily understood and directly translated into logical rules, making them highly interpretable. These models can be represented as a series of conditions and actions that are clearly articulated and traceable.

BTW, LLMs are the antithesis of symbolic. In fact, “Symbolic AI” is essentially the term that differentiates LLMs from Prolog and KGs.

For example, a decision tree rule in a business context might state something like:

If a customer's credit score is less than or equal to 600, and their annual income is less than $50,000, then classify the customer as high-risk for loan approval.

In Prolog, that rule would look something like:

% Define the rule for classifying a customer as high-risk

high_risk(Customer) :-

credit_score(Customer, Score), Score =< 600,

annual_income(Customer, Income), Income =< 50000.

Although this rule is of course a generalization (probabilistic), it’s clear and actionable, directly translating business criteria into a decision-making process. If the condition of having a credit score ≤ 600 and an annual income ≤ $50,000 is met, the decision tree automatically classifies the customer as high-risk. Such rules help businesses automate and standardize their decision-making processes, ensuring that consistent criteria are applied when assessing risk, approving loans, or making other important decisions. This type of rule can be easily represented in a Prolog system, where conditions and outcomes can be modeled and queried logically.

On the other hand, linear regression and logistic regression (support vector machine is another good example) models are more “algebraic” in nature. They are centered on mathematical operations and functions to determine outcomes. For example, a linear regression is in the form of y=β0+β1+x1.

Linear regression uses a weighted sum of input features to predict a continuous output, while logistic regression applies a logistic function to produce a probability for binary classification. These models are inherently numerical, leveraging arithmetic operations like multiplication and addition, which can be seamlessly implemented in Prolog using its arithmetic capabilities. This allows the models to be integrated into a logic-based system, though the underlying processes are more mathematically driven rather than purely symbolic. The algebraic nature of these models offers a different approach to prediction and classification, complementing the more rule-based methodologies of symbolic models.

This blog includes a sample walkthrough as an example of transforming decision tree rules into Prolog.

Machine Learning Heuristics

As I’ve mentioned, ML models are probabilistic. That means they are generalizations. For example, although I’m of Japanese ancestry, I really don’t care for raw seafood dishes such as sushi and sashimi. I don’t think in this day I need to write about the dangers of generalizations. The world is too complex to doggedly stick to generalizations. But whatever we’ve each learned based on our years of unique observations are mostly beneficial to our survival than detrimental.

So even though I refer to “rules”, ML models are heuristics at best. Heuristics are rules of thumb or simplified approaches that help us make decisions or solve problems more efficiently by using practical methods rather than strict logic or exhaustive analysis. They rely on experience, intuition, and educated guesses to quickly reach conclusions in situations where a full, detailed analysis might be too time-consuming or complex. In the case of ML, heuristics are based on statistics derived from many examples in a structured data.

The reason I bring this up is because up until now, I’ve been talking about Prolog as deterministic encoding of knowledge. That is, compared to LLMs, which are fuzzy encodings of knowledge. Both are trained on usually massive data sets in an automated fashion (the learning is automatic). The advantage of the former is that the encodings are more controllable than that of the latter. On the other hand, LLMs can be trained and a highly heterogenous and deep corpus of unstructured data.

As I mentioned earlier, ML models are in that middle “Goldilocks” position – more control over the training than LLMs, but not requiring the hand-holding of coding, whether Prolog or Python. With ML models, we (data scientists) control what data is fed into the ML algorithm, but we don’t directly control the rules/heuristics/patterns it derives from the data. If we wanted direct control, we would directly encode it in a programming language.

Human experts may sometimes validate the logic underlying the rules that form ML models, but more often, validation is conducted in a way that supports automation—typically through metrics derived from true positives, false positives, true negatives, and false negatives (precision, accuracy, recall, etc.). This automated approach allows for efficient evaluation and tuning of models based on statistical performance rather than manual inspection.

However, with the advent of LLMs, there is now the potential to sanity-check ML models by examining and interpreting the underlying rules more intelligently. This could introduce a layer of scrutiny that aligns more closely with human reasoning, though it may also slow down the process of deploying updated ML models if human validation becomes a prerequisite. And LLMs aren’t yet smart enough to trust unsupervised in production. The challenge is to balance the need for robust, accurate models with the efficiency required to keep pace in dynamic environments.

Why Mix ML into Prolog?

So why bring Prolog into the mix? Yet another layer of complexity. Well, that’s pretty much what Part 1 is all about. It starts with the fact that LLMs have their weaknesses – at the time of writing. Mostly, they hallucinate, they’re very poor at original thinking, and the cost of querying LLMs doesn’t make sense if we know the well-defined rules.

In Part 1, I mentioned that the notion of Prolog in the LLM era is very similar to that of knowledge graphs (KG) in the LLM era. Prolog and RDF-based (Resource Description Framework) KGs are both about encoding knowledge, mostly in a deterministic manner. Prolog is logic-based, KGs are ontology-based. Roughly, Prolog are Boolean logic statements, while ontologies are graphs of “is a”, “a kind of”, and “has a” relationships between things.

Prolog and RDF

RDF is primarily about uniquely identifying resources on the web through URIs (Uniform Resource Identifiers). RDF is a framework, developed in the W3C, for representing information about resources in a graph format, with a focus on making relationships between objects clear and universally accessible. The use of URIs for uniquely identifying objects allows RDF to provide a standardized way of referring to objects, enabling interoperability across different systems and domains.

Prolog, on the other hand, is a logic programming language focused on deductive reasoning and rule-based logic. While Prolog excels at reasoning about relationships and applying logical rules, it doesn’t inherently provide a mechanism for universally identifying objects across different systems in the way that RDF does with its use of URIs. Prolog identifiers are usually local to the Prolog environment and don’t have the global uniqueness that RDF URIs offer.

Note that SWRL (Semantic Web Rule Language) is a language in the RDF world designed to add rule-based logic to OWL ontologies within the RDF framework. But it lacks the full expressiveness and computational power of a dedicated logic programming language like Prolog. SWRL’s use cases are primarily limited to simple inferencing in ontologies, making it less versatile for complex reasoning tasks compared to Prolog.

Prolog can indeed leverage RDF definitions and identifiers when working within the broader context of the semantic web. For example, this Prolog states Microsoft is located in the United states. It uses the Microsoft URL and a definition of the United States from FIBO as unique identifiers.

located('http://www.microsoft.com', 'fibo:Corporation:UnitedStates').

By incorporating RDF data or interfacing with RDF-based systems, Prolog can leverage the unique identifiers provided by RDF to reason about globally recognized entities, thus combining Prolog’s powerful reasoning capabilities with RDF’s universal identification framework.

This combination allows Prolog to participate in the semantic web, where it can apply logical rules to data that has been uniquely identified and structured using RDF, effectively bridging the gap between logic programming and semantic web technologies.

Where do the Rules Come From?

When I demoed SCL back in 2004 and laid out the plan I had for it, someone asked me where the rules come from. I said that it’s authored by people, it’s a method for encoding their knowledge into an “expert system”. He mentioned how tough it is to encode rules even of a relatively simple system.

I understood the difficulty but thought it to be at least within the magnitude of the difficulty of writing a comprehensive technical book or enterprise-class software. It really is tougher to express knowledge in Prolog than in words or programming code. In words, the readers of the book come with a prerequisite sense of much of how the world works – basic physics, inter-personal skill, years of experience just living, etc. In Prolog, all that needs to be spelled out. In a coding language like C# or Java, the syntax is very expressive, intended for more than defining logical rules.

Well, so how can we automate the composing of rules? In 2004, data mining (predictive analytics, machine learning, whatever) was still fringe – but awareness of it was rapidly spreading.

Back in Part 2, I introduced the concept of the MetaRules extension of the Prolog variant I wrote back in 2004, SCL (Soft-Coded Logic). The main idea is to import the rules of ML models (I mostly called them “data mining” back then) into Prolog. For example, rules from a decision tree model for predicting what category of car might be of interest to a customer:

predicted_car_model(@custid,Sedan) :- occupation(engineer), @age>50.

predicted_car_model(@custid,Sports) :- occupation(lawyer),

@age>30 && @age|50.

predicted_car_model(@custid,Truck) :- occupation(farmer), @age>20.

ML to Prolog Walkthrough

This section of the blog focuses on the application of translating ML models into Prolog rules. By doing so, it demonstrates how probabilistic decision-making can be encoded in a logical framework, allowing for seamless integration between ML-driven predictions and rule-based reasoning.

The accompanying code walkthrough is a step-by-step example of how to accomplish this translation. You’ll start by creating an ML model using a Decision Tree classifier trained on the well-known Iris dataset. This model is then used to extract logical rules, which are converted into a format compatible with Prolog. Finally, the rules are tested in Prolog against the original ML model to ensure consistency.

This approach not only highlights the interoperability between different AI paradigms but also underscores the potential for combining the probabilistic nature of ML with the deterministic logic of Prolog, resulting in a powerful tool for decision-making processes. The code and detailed explanations provided here are a great starting point for those interested in exploring this hybrid approach.

The code mentioned in this section can be found at:

https://github.com/MapRock/IntelligenceBusiness/tree/main/book_code/appendix_c

Create an ML Model

This Python script, iris_prolog_rules_0.py, trains a machine learning model on the ubiquitous Iris dataset using a Decision Tree classifier. The script begins by determining the directory of the current script and adjusting the path format for compatibility with Prolog. It then loads the Iris dataset, which contains measurements of iris flowers and their corresponding species. The Decision Tree classifier is trained on this dataset to create a model that can classify iris flowers based on their features. Finally, the trained model is saved as a .pkl file in the same directory as the script, allowing it to be loaded and used later for predictions.

# iris_prolog_rules_0.py

from sklearn.datasets import load_iris

from sklearn.tree import DecisionTreeClassifier

import joblib

import os

# Get the directory of the current script.

# Prolog needs / instead of \ in the path.

current_directory = os.path.dirname(os.path.abspath(file)).replace("\", "/")

# Load the Iris dataset

iris = load_iris()

X, y = iris.data, iris.target

# Train a Decision Tree classifier

clf = DecisionTreeClassifier(random_state=42)

clf.fit(X, y)

# Save the model as a .pkl filepkl_file = f'{current_directory}/decision_tree.pkl'

joblib.dump(clf, pkl_file)

This is the set of rules created by the code above:

The “class” items are varieties of irises: 0=setosa, 1=versicolor, 2=virginica

Extract Rules from the ML Model to Prolog

iris_prolog_rules_1.py bridges ML with logic programming by converting a decision tree model into Prolog rules. It begins by loading the pre-trained decision tree model we just created from the famous Iris (flower) dataset, stored as a .pkl file. The Iris dataset contains features like petal and sepal measurements, which are used to classify iris flowers into three species.

The core of the script involves a function that translates the decision tree’s structure into a set of Prolog rules. These rules represent the conditions and outcomes of the decision tree in a symbolic format that Prolog can process. The core function, generate_prolog_rules, extracts the decision paths from the tree, converting them into logical rules with probabilities attached to each outcome.

The script then saves these Prolog rules into a .pl file, making them ready for use in a Prolog environment. The rules can be loaded into a Prolog interpreter to classify new instances based on the model’s logic, combining machine learning with rule-based reasoning.

p(_,_, Petallengthcm, , setosa, 0.33) :- Petallengthcm =< 2.45.

p(, , Petallengthcm, Petalwidthcm, versicolor, 0.00) :- Petallengthcm > 2.45, Petalwidthcm =< 1.75, Petallengthcm =< 4.95, Petalwidthcm =< 1.65.

p(, , Petallengthcm, Petalwidthcm, virginica, 0.50) :- Petallengthcm > 2.45, Petalwidthcm =< 1.75, Petallengthcm =< 4.95, Petalwidthcm > 1.65.

p(_, _, Petallengthcm, Petalwidthcm, virginica, 0.09) :- Petallengthcm > 2.45, Petalwidthcm =< 1.75, Petallengthcm > 4.95, Petalwidthcm =< 1.55.

p(_, _, Petallengthcm, Petalwidthcm, versicolor, 0.98) :- Petallengthcm > 2.45, Petalwidthcm =< 1.75, Petallengthcm > 4.95, Petalwidthcm > 1.55, Petallengthcm =< 5.45.

p(_, _, Petallengthcm, Petalwidthcm, virginica, 0.00) :- Petallengthcm > 2.45, Petalwidthcm =< 1.75, Petallengthcm > 4.95, Petalwidthcm > 1.55, Petallengthcm > 5.45.

p(Sepallengthcm, _, Petallengthcm, Petalwidthcm, versicolor, 0.00) :- Petallengthcm > 2.45, Petalwidthcm > 1.75, Petallengthcm =< 4.85, Sepallengthcm =< 5.95.

p(Sepallengthcm, _, Petallengthcm, Petalwidthcm, virginica, 0.67) :- Petallengthcm > 2.45, Petalwidthcm > 1.75, Petallengthcm =< 4.85, Sepallengthcm > 5.95.

p(_, _, Petallengthcm, Petalwidthcm, virginica, 1.00) :- Petallengthcm > 2.45, Petalwidthcm > 1.75, Petallengthcm > 4.85.

Here’s how the Prolog rules translate into English:

- Rule 1: If the petal length is 2.45 cm or less, the iris is predicted to be a setosa with a probability of 33%.

- Rule 2: If the petal length is greater than 2.45 cm and the petal width is 1.75 cm or less, and the petal length is 4.95 cm or less, and the petal width is 1.65 cm or less, the iris is predicted to be a versicolor with a probability of 0%.

- Rule 3: If the petal length is greater than 2.45 cm, and the petal width is 1.75 cm or less, and the petal length is 4.95 cm or less, and the petal width is greater than 1.65 cm, the iris is predicted to be a virginica with a probability of 50%.

- Rule 4: If the petal length is greater than 2.45 cm, and the petal width is 1.75 cm or less, and the petal length is greater than 4.95 cm, and the petal width is 1.55 cm or less, the iris is predicted to be a virginica with a probability of 9%.

- Rule 5: If the petal length is greater than 2.45 cm, and the petal width is 1.75 cm or less, and the petal length is greater than 4.95 cm, and the petal width is greater than 1.55 cm, and the petal length is 5.45 cm or less, the iris is predicted to be a versicolor with a probability of 98%.

- Rule 6: If the petal length is greater than 2.45 cm, and the petal width is 1.75 cm or less, and the petal length is greater than 4.95 cm, and the petal width is greater than 1.55 cm, and the petal length is greater than 5.45 cm, the iris is predicted to be a virginica with a probability of 0%.

- Rule 7: If the petal length is greater than 2.45 cm, and the petal width is greater than 1.75 cm, and the petal length is 4.85 cm or less, and the sepal length is 5.95 cm or less, the iris is predicted to be a versicolor with a probability of 0%.

- Rule 8: If the petal length is greater than 2.45 cm, and the petal width is greater than 1.75 cm, and the petal length is 4.85 cm or less, and the sepal length is greater than 5.95 cm, the iris is predicted to be a virginica with a probability of 67%.

- Rule 9: If the petal length is greater than 2.45 cm, and the petal width is greater than 1.75 cm, and the petal length is greater than 4.85 cm, the iris is predicted to be a virginica with a probability of 100%.

Validate Prolog Against the ML Model

iris_prolog_rules_2.py tests the consistency between predictions made by a trained machine learning model (a Decision Tree) and corresponding Prolog rules generated from that model. It first loads the Iris dataset and the pre-trained Decision Tree model from a .pkl file. The script then uses this model to predict the class of an iris flower based on given input features and prints the probability distribution for each class.

The script also initializes a Prolog environment and loads the Prolog rules derived from the same Decision Tree model. It constructs a query using the same input features and executes this query in Prolog to classify the iris flower. Finally, the script compares the predictions and probabilities from both the Decision Tree model and the Prolog rules, printing the results to verify if the two methods produce consistent outcomes.

This test ensures that the logical rules extracted from the Decision Tree are accurately represented in Prolog and that the two systems provide matching predictions for the same input.

iris_prolog_rules_2.py is relatively long for this blog. You can see it here:

This is the result of running that script:

Probabilities for each class: {'setosa': 0.0, 'versicolor': 0.0, 'virginica': 1.0}

Prolog query: p(1.0, 4.5, 5.0, 5.5, Guess, Probability)

Prolog Guess: virginica, Probability: 1.0

The result shows that both the ML model and the Prolog rules correctly classify the given iris flower as “virginica” with a probability of 1.0. This indicates that the Decision Tree model, when given the input features [1.0, 4.5, 5.0, 5.5], predicts the flower as “virginica” with complete certainty. Similarly, the Prolog query derived from the same model’s rules returns “virginica” with a probability of 1.0, confirming that the Prolog rules accurately replicate the behavior of the trained machine learning model for this input. This consistency demonstrates the successful translation of the decision tree’s logic into Prolog rules, ensuring that both systems provide identical predictions

Query-Time Prolog Composition

This example demonstrates how Prolog can be used not just for logic and reasoning but also for triggering actions based on those decisions, effectively integrating decision-making logic with real-world actions in a Python environment.

The Prolog code just below defines a new rule, send_if_iris_found, which not only classifies an iris flower using the previously generated Prolog rules but also takes an action based on the classification. If the predicted probability of the flower being a specific species (for example, virginica or versicolor) is greater than 0.5, the system prints a message indicating the classification and that an email is being sent to a friend (for demonstration purposes, it only prints a message).

:- consult('.../iris_prolog_rules.pl').

% New rule to take action based on the classification

send_if_iris_found(Sepallen, Sepalwid, Petallen, Petalwid) :

p(Sepalleng, Sepalwi, Petallen, Petalwid, Guess, Probability),

Probability > 0.5,

format('This iris is ~w with probability ~2f. Sending email to your friend…\n', [Guess, Probability]),

true.

The Python script (iris_prolog_rules_3.py) sets up the Prolog environment, loads the Prolog rules, and runs queries to classify two different iris flowers. Based on the results of these classifications, it triggers the send_if_iris_found rule, which simulates sending an email notification if the classification probability is high enough.

# iris_prolog_rules_3.py

from pyswip import Prolog

import os

# Get the directory of the current script.

# SWI-Prolog seems to need / instead of \ in the path.

current_directory = os.path.dirname(os.path.abspath(file)).replace("\", "/")

prolog = Prolog()

# Load the Prolog rules generated from the decision tree

prolog.consult(f"{current_directory}/iris_prolog_rules_action.pl")

# Execute a query to classify the same iris flower based on its features using Prolog

# Virginica, 1.00

list(prolog.query("send_if_iris_found(5.8, 2.7, 5.1, 1.9)."))

# Versicolor, 0.98

list(prolog.query("send_if_iris_found(5.8, 2.7, 5.1, 1.6)."))

This is the result of the two prolog.query statements at the end of the code:

This iris is virginica with probability 1.00. Sending email to your friend…

This iris is versicolor with probability 0.98. Sending email to your friend…

Conclusion

In this fourth part of Prolog’s Role in the LLM Era, we’ve delved into the intersection of Prolog and Machine Learning (ML) models. By translating decision tree rules into Prolog, we’ve demonstrated how these two distinct approaches—one rooted in symbolic logic and the other in probabilistic generalization—can be harmonized. This integration allows us to leverage the deterministic reasoning power of Prolog while benefiting from the data-driven insights that ML models offer.

Prolog’s capability to process logical rules makes it an excellent partner for ML models, especially when those models can be distilled into a set of human-understandable rules. The symbolic nature of decision trees, clustering, and association rules aligns well with Prolog’s logical structure, enabling a clear and interpretable form of knowledge representation. Meanwhile, algebraic models like linear and logistic regression can also find their place in Prolog through its arithmetic capabilities, though their integration is more mathematical than symbolic.

By converting ML models into Prolog rules, we create a robust framework that combines the strengths of both approaches, providing a powerful tool for reasoning, decision-making, and even taking actions based on the outcomes of these models. This synergy between Prolog and ML not only enhances our ability to understand and utilize data but also opens up new possibilities for creating intelligent systems that are both interpretable and actionable.

As we continue to explore the potential of Prolog in the LLM era, it becomes increasingly clear that this combination of deterministic and probabilistic reasoning holds great promise for the future of AI, particularly in domains where clarity, control, and precision are paramount.

In Part 5, we’ll explore the integration between our OLTP and OLAP databases with Prolog.