Original thinking doesn’t spring from a void. It’s the meticulous art of forging a path to a solution where none yet exists, of stitching together lessons from far-flung domains to carry us from where we are to where we wish to be. In everyday life, we rely on zero-sum games—win or lose, right or wrong—yet true original creativity demands something more expansive. It asks our minds (or our knowledge graphs) to reach beyond the familiar—to think outside of the graph—to see that a poem and a factory line, a Zen koan and a surgical protocol, can inspire solutions for seemingly unrelated problems.

Every saying, cliche, meme, parable, proverb, aphorism, simile, historical case study, and glossary of corporate jargon is the evolved version of what originated as an observation of nature’s processes by a sentience—water finding a new channel, seeds sprouting in unlikely soil, the eternal struggle between predator and prey. Over generations, those witnessed nature-originated patterns were passed from person to person, refined, combined and re-combined into the analogies (and metaphors) that now populate our languages and our collective memory.

What if we treated those step-by-step analogies as first-class knowledge artifacts, storing them not just as text, but as procedural graphs embedded and linked into large knowledge graphs. They are Time Molecules, each node an event, each edge a probability of what comes next.

By harvesting processes from every corner of human experience—and even from the natural world itself—we build a library of procedural wisdom. When faced with an unfamiliar challenge, we map our current state and our desired outcome into that graph, let AI help bridge the semantic gaps, and follow the probabilistic trails laid down by evolution, by invention, by trial and error. In this way, every solution becomes a process, and every process becomes an invitation to create—drawing on analogies both ancient and cutting-edge to light the way forward.

A solution isn’t a static picture—it’s a process or system. It’s when we embed an idea into a chain or web of events that it truly matters. For example, a PhD on its own is just a credential. It only generates value when it feeds into hiring decisions, project outcomes, or strategic pivots. Likewise, every analogy you spot is really a tiny process template—a little Markov chain you can graft onto your current challenge. We might call these “memes”: abstract, portable process blueprints that an LLM can surface and map onto the problem at hand. In this way, creativity becomes recombining processes, not just swapping metaphors.

The end product of my book, Time Molecules, is a graph of engineered or discovered processes collected mostly from existing enterprise databases, and now from rapidly growing populations of IoT (Internet of Things) devices and AI agents. But what if we purposefully collected processes beyond our enterprise, to processes that probably have nothing to do with our business or even nothing to do with business itself? That would be a fountain of analogies, a powerful source of creative and original thinking.

This is Part 3, the final part of a trilogy that dives deep into the intuition for Time Molecules—not the business use case or its place in the technical zoo, but how we must be cognizant of the mechanisms for decision-making and creative analysis, human or AI:

- From Data Through Wisdom: The Case for Process-Aware Intelligence – An exploration of the nature of intelligence, particularly critical, creative, and original thinking.

- Thousands of Senses – An intelligence requires the ability to consider data that might include a few to dozens of elements from pools of thousands to millions of sources.

- Analogy and Curiosity-Driven Original Thinking

A warning though. Because this blog is about analogy and metaphor, you’ll notice the dozens in here that you otherwise wouldn’t have noticed. Almost everything we say can’t help but be some sort of analogy or metaphor to some degree.

Key Takeaways

- Profound Intelligence is Original Thinking: The ability to generate novel solutions to novel problems.

- Solutions Are Processes: Every answer unfolds as a sequence of steps. Thinking of solutions this way lets us treat them as first-class citizens in our repository.

- Time Molecules is a Process Library: Just as Wikidata stores facts and ontologies, Time Molecules stores millions of event-sequence cases—from factory lines to medical protocols, including the extremely long tail of invention from those who are not household names.

- Analogy is Pattern Matching: Solving a novel problem means finding a familiar process whose relational structure aligns with your current challenge.

- Ontology vs. Analogy: Ontologies tell you what exists; analogy tells you how to apply existing solutions to new contexts.

- Experience Expands Your Pool of Analogy Possibilities: The richer your library of processes, the more likely you’ll find a distant-domain match that sparks a breakthrough.

- LLMs as Analogy Pattern Scoring Engines: Large models excel at judging pattern similarity across disparate processes, but they still need careful framing and iterative refinement to surface the best analogies.

A Couple of Housekeeping Items

- Time Molecules (and my previous book, Enterprise Intelligence) are available on Amazon and Technics Publications. If you purchase either book (Time Molecules, Enterprise Intelligence) from the Technic Publication site, use the coupon code TP25 for a 25% discount off most items.

- For an overview of Time Molecules itself, please see my blog: Sneak Peek at my New Book – Time Molecules

- My goal for Time Molecules and Enterprise Intelligence isn’t to power a mega surveillance grid, but to share my own insights with fellow data engineers, data scientists, and knowledge workers. I want us to stay rooted in the real world—its events, its processes, its context—rather than lean blindly on whatever an AI tells us. In other words, somewhere between those elite AI researchers and those who learn enough about AI for it to better tell us what to do. At the end of the day, human judgment remains the bedrock of true intelligence. Remember, AI is currently, in many ways, just “smart enough to be dangerous”.

Everything is a Process

The subtitle of Time Molecules is: The BI Side of Process Mining and Systems Thinking. It treats every change—whether a clock tick, the onset of rush hour, or the unfolding of a plant’s seasonal cycle—as an event and captures it in a unified (CaseID, DateTime, Event) table. From that raw event ensemble we automatically derive many thousands of Markov models—one per observed process or system loop, sliced by unique tuples of features—each a condensed procedural graph of nodes (events) and edges (transition probabilities and timing metrics). In this way, what would otherwise be formless chaos congeals into a tapestry of interacting systems: grocery supply chains ripple into consumer behavior, traffic patterns feed into urban planning, even ecological cycles intertwine.

Because everything with a timestamp is an event, the sample solution that goes along with Time Molecules, TimeSolution, can ingest data from any domain into a central repository. Layer on LLM-powered embeddings against each event’s human or auto-generated description, and you gain the power to spot analogies across those Markov graphs—asking, for instance, “Which historical process resembles turning a seed into a sapling or cracking an egg into life? How is Mu Shu pork like a burrito, or rice in Japan like pasta in Italy?” It’s precisely because solutions are processes that distilling our world into event-based Markov models creates the perfect substrate for original thinking by analogy.

Solutions

A solution is a process, a set of tasks towards a desired outcome. Tasks could be run in parallel, and tasks could themselves be nested processes. At whatever level, tasks start with a state and end with another state, a milestone in our solution. Solutions could involve a single task like deciding to throw a curve ball for strike three or it’s just plugging in the vacuum cleaner cord that pulled out. But the most profound solutions involve planning more than one step ahead. The more steps ahead we’re able to plan with high fidelity, the better we are, just like a chess player who can see more steps ahead than her opponent.

How Solutions are Formulated

We can find inspiration for solutions in a number of ways. A solution encompasses steps to get from point A to point B. A solution is a process. For example, if we’re standing at the precipice of a canyon and need to get to the other side, we need to find a usable path. That search for a solution can range from just trying different directions until we run into a dead end to asking someone who has already stumbled upon or was taught about a path, to inventing and building a helicopter.

Following are a few ways that we find solutions, from the least to the most sophisticated.

Random Search

We could just try a whole bunch of random different stuff. It reminds of me Siddhartha, the titular character of Herman Hesse’s great book, who left the safety of his family’s castle and roamed around for many years looking for “something”—what that was, he had no idea. But there is value in this method. I recall one of my judo instructors telling me to just roll around on my back to learn all the different ways I might get back up, ways that he wouldn’t have known to suggest. Those random possibilities might not have be useful in the moment, but perhaps in some future match, having experienced it might give me the unexpected move I need.

The problem is that it takes an unknown amount of time, anywhere from the next instant to well after the Universe is done, with no guarantee for any sort of helpful result.

Monte Carlo Combinatorial Search Space

A step beyond “throwing darts in the dark” is to explore combinations of features systematically. We can narrow our search by focusing on a handful of key factors—after all, most real-world problems already live within natural, unique sets of constraints. For example, if you want to open a novel restaurant, you’re limited by FDA-approved ingredients, health codes, your budget, local tastes, and even laws against endangered-species menus. Yet even within those bounds, the number of possible menus, layouts, and service models still dwarfs what any team could manually test. That’s the dreaded combinatorial explosion—an astronomical surge of options that no amount of intuition alone can tame.

Imagine a relatively common and simple scenario where you wanted to evaluate every combination of:

- 1000 potential restaurant locations

- 100 ad-campaign strategies

- 1,000 ingredient bundles

- 100 customer segments

- 100 price-point tiers

Multiplying those together gives you ten trillion unique combinations. Keep in mind that adding even one more dimension further multiplies those combinations! In reality, most business situations involve many more dimensions that what I listed. And most algorithms into which we plug in those features also involve a number of hyperparameters that tweak the algorithm.

Granted, the Monte Carlo algorithm can reduce the number of combinations through techniques such as random sampling, dimension reduction, and statistical inference to approximate the best solutions without exhaustively checking every possibility.

Even a Monte Carlo sampler running millions of trials would barely scratch the surface, which means you still need smarter ways to prune, bias, or guide your search beyond pure randomness.

Ask Someone (Learning from the Known)

We could ask someone who might have ideas for a solution to our problem. Or research a known solution someone was kind enough to share—through Web searches, Wikipedia, books, blogs, videos, Stackoverflow and Reddit posts, etc. Whatever the source, a known solution might be out there. Whatever method, we’re learning about known solutions, where someone some time ago already went through the burden of discovery.

For the types of problems requiring a high degree of training, we would first consult “experts” such as doctors for medical advice and lawyers for legal advice. The doctor will prescribe a treatment plan, a set of actions. A lawyer will hold our hand through a legal process.

The problem with experts is they might have trouble with a novel solution. Hopefully a highly-experienced expert will have “seen it all” and can readily solve most of your problems that fall within their domain.

But what about domains for which there are few if any experts or they are too expensive? Today, with social media (X, Reddit, Quora, blogs) and the self-publishing marvel of Kindle books, we have access to experience across an unimaginable range of domains and rare experiences. Across a fair chunk of humanity, there is a reasonable probability someone has experienced what we experienced, but it didn’t warrant attention from a major publisher.

Of course, asking implies that we’re willing and able to learn. Learning about something that is explained is relatively easy. Even for something that’s difficult to learn such as math, it’s relatively easy to learn about it compared to what the likes of Euclid, Newton, and Euler had to go through inventing their novel paradigms.

With basic skills trained in our brains—the ability to freely walk around, use our hands, communicate, etc.—sometimes it just takes one word or one action from someone else to trigger the lighting of the path to the solution to our problem. Whatever the mechanism—neural plasticity, mirror neurons, and all that stuff—If we couldn’t learn, we wouldn’t be the sentient and sapient folks we are today.

Where did these ideas come from? We learned it from others, who learned it from others, who learned it from others … Over time, what we learned evolved—adjusted to a slightly different set of circumstances. But where did these idea originate?

As a nature-lover, I know that just observing something in natural has inspired ideas—like Newton’s apple and Archimedes of Syracuse (who formulated the principle that an object submerged in a fluid is buoyed up by a force equal to the weight of the fluid displaced), and perhaps some hominid from hundreds of thousands of years ago who saw a rock fall on someone’s head and envisioned a way to use rocks as a lethal hunting tool.

But we’ve gone well beyond those seeds of invention that we initially learned from others or nature. From the original insights, we’ve devised chains of novel solutions to novel problems—at a pace much faster than it took evolution to invent those initial inspirations we observed in nature.

First, we can go further with what we’ve learned. As Heraclitus says, we never step into the same river twice. That exact situation will not come about again. it would be awful if we couldn’t re-apply something we’ve learned. So, we’re able to generalize.

Abstraction works because the world is a very fuzzy place, full of imperfect information of many forms. But on the other hand, the world is made up of patterns. this means things aren’t exact and the situation presented isn’t always exact.

My suspicion is that the ability to abstract was originally a bug, not a feature. it’s easy for ancient creatures to distinguish hot and cold, light and dark, and maybe even up and down and left to right. But as life became more complex, the decisions became more complicated as well, no longer simply binary. but our machinery wasn’t perfect, especially in an imperfect world. without the imperfection, we’d miss much—lots of false negatives, missing things that are there, but doesn’t fit the rule exactly. This is why machine learning models should not be too good for their own good–they could be over-trained, meaning it requires the exact conditions, which will probably not happen. in manufacturing, exactness is needed for products, but those are rules.

The ability to abstract, which might also be thought of as naturally faulty recognition inherent of a complex world of imperfect information, prevented false negatives. So, perhaps this faulty mechanism started as a bug but is now a feature. The inability to measure exactly is actually a good thing.

We can recognize things in a wide variety of ways without ever having seen those different angles, lighting, obscured views, etc. False negatives in our modern world are tougher to deal with than false positives—at least we can see false positives. False negatives don’t have a signal like false positives—a potential terrorist getting through TSA (false negative) won’t say anything like grandma patted down (false positive) for “extra security”. In fact, almost all of us are false positives, with a few true positives (actual terrorists caught by the TSA) and hopefully no terrorists who got through (false negatives).

To summarize, learning is relatively easy compared to inventing, and our ability to abstract/generalize enables us to apply what we’ve learned in varying forms of the original situation. It’s one thing to drive my own car then to also be able to drive a randomly assigned rental car or know what to expect when I enter a Denny’s or other diner for a meal. but it’s another thing when I need to revolve a novel situation and googled it but no one seems to have ever faced it before, or I don’t have internet access and can’t access any other knowledge base (human, book, video, or blog).

Analogy

Barring all that, I can realize only a minority of people in the world have written a book or article or even posted anything substantial on the internet. Still, there is all that iceberg under the water that isn’t recorded anywhere but in isolated locales.

How do we find this knowledge that vaporizes from the universe with the person who developed it? There’s yet the old-fashioned route of scouring the world looking for the reclusive guru somewhere in the mountains who might have the answer. Or stumbling onto someone who cobbled together some ingenious contraption

But sometimes, we’re “fortunate” enough to face truly novel situations requiring truly novel solutions. Where do these novel solutions come from when there are no seeds to start with? They can come from far out abstractions, analogies that require a stretched imagination to see. The crazy things that only crazy people apparently see.

Let’s explain analogy with an analogy: Every novel solution (or at least novel as far as we can tell) begins with an idea. Every idea is an analogy, think of it as a conceptual model, of some unrelated solution that was already learned. Ideas are never fully-formed solutions, but start as seeds that are forged through iterations of growth until they become a fully-formed solution—logical and physical models.

I should mention that analogies can be taken too far. Just as “correlation doesn’t imply causation”, we can also say, “analogy does not imply identity”. At some point analogies do break—analogies are made to be broken— leading us down misguided paths. We then just stop there, grateful for the seed of the idea.

Semantic Web AnalogousTo Relationship

In the realm of solutions patterns and relationships, analogy is the pattern-side counterpart to the relationship-side of “Connecting the Dots”. Both are about creating missing information or knowledge that is unavailable to us for whatever reason, and both require imagination. Connecting the dots is about seeing relationships that haven’t yet been seen, while analogy is about seeing similarity between patterns.

The Semantic Web, through standards like RDF, RDFS, and OWL, is great at capturing well-defined relationships—things like rdf:type (is a), rdfs:subClassOf (a kind of), and owl:sameAs (literally the same). These form the backbone of taxonomies and ontologies, letting us build structured hierarchies of knowledge. But there’s something it doesn’t quite capture: analogy.

Analogical reasoning is different. It doesn’t say “this is that” or “this inherits from that”—it says “this is like that, in some important way, even if this and that are in different subjects.” It’s relational, cross-domain, and often fuzzy. Saying a CEO is to a company as a conductor is to an orchestra is a kind of structural similarity—but it doesn’t fit into any of the standard RDF predicates.

To my knowledge, there’s no commonly used analogousTo relationship in RDF/OWL (specifications for the Semantic Web, knowledge graphs). You can define one yourself, but you’re stepping outside traditional ontology work and into something closer to creative inference. Analogy isn’t about categories—it’s about mapping roles, functions, and patterns across different conceptual spaces.

One of the foundational problems with knowledge graphs is the same problem we’ve always had with databases: the absence of a value—or a relationship—can mean one of two things. Either it truly doesn’t exist, or we just haven’t added it yet. A missing relationship between two nodes might signal there’s no connection, or it might just reflect incomplete research.

When a reasoning engine uses a knowledge graph as its “database,” it’s treating that graph as the full extent of what’s known. But of course, we know the graph doesn’t know everything. So how can we trust the conclusions it draws? We might say, “well, test it—if it gets the right answer, we’re good.” But that logic breaks down at the edges, and those edges are where Black Swans live. The danger isn’t in what the graph tells us—it’s in what it doesn’t, and in the quiet assumption that if something isn’t connected, it must not matter. That’s a brittle kind of intelligence.

And that might be where symbolic logic meets intuition—where ontologies start to hint at creativity.

For example, I asked ChatGPT:

In 200 words what is the best analogy between seeds and eggs, and offer a 0 to 1 score.

Code 1 — Asking ChatGPT to measure analogous similarity seeds and eggs.

It responded:

Seeds and eggs are both nature’s compact blueprints for life, each housing the potential for a complex organism—but the analogy reveals key contrasts in how life is initiated and supported.

A seed is like a self-contained instruction manual wrapped in a suitcase of supplies. It carries the genetic code (embryo) and some nutrients, but it waits passively for the right external conditions—moisture, warmth, soil contact—to activate. Germination begins when the world gives it a green light.

An egg, especially in animals, is more like a prepaid incubator. It contains the embryo, yes, but also a full meal plan (yolk, albumen), often surrounded by a protective shell or membrane. Fertilization typically happens before external conditions are optimal. The egg then develops under the care of its parent or an environment calibrated for life.

In short:

- Seed = Self-sufficient start, but waits for the world to act.

- Egg = Pre-equipped and proactive, but requires early intervention (fertilization).

The analogy works best in showing both as containers of life with differing dependencies and timing triggers.

Score: 0.83 — Strong analogy, especially in educational contexts, though imperfect due to differences in fertilization timing and parental involvement.

Code 2 — Response from ChatGPT to Code 1 question

We can extend the analogy of egg to seed to their respective parts, as shown in Table 1.

| Seed Component | Egg Component | Functional Role | Analogy Score | Justification |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Husk | Shell | Rigid outer protection | 0.85 | Both form the hard, external barrier that shields the developing embryo from physical damage. |

| Endosperm | Albumen | Nutrient reservoir | 0.80 | Each supplies water-soluble proteins and carbohydrates to fuel early growth of the embryo. |

| Germ | Blastodisc | Embryonic precursor | 0.90 | Both are the microscopic cell masses that actually give rise to the new plant or chick. |

| Cotyledon | Yolk | Stored food for seedling growth | 0.60 | In some seeds, cotyledons absorb or hold the endosperm’s nutrients, analogous to the yolk’s role. |

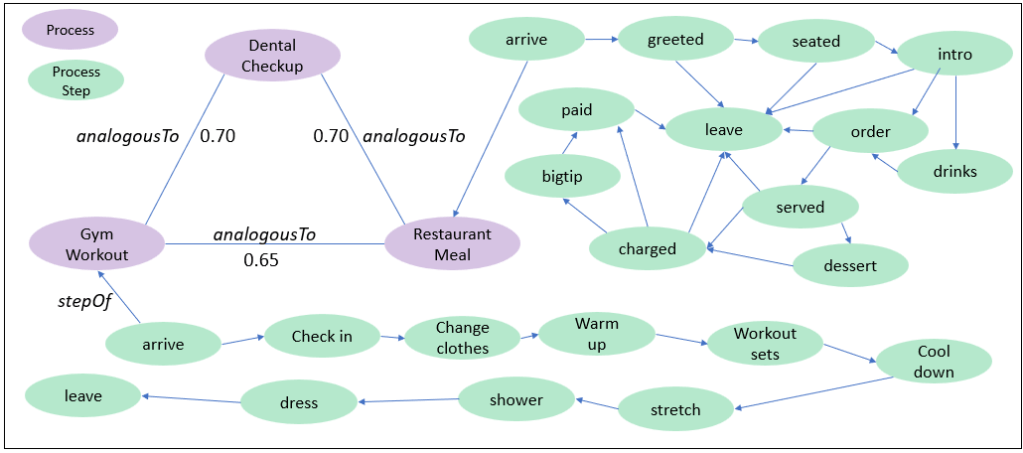

Figure 1 shows an example of how the score of the analogous similarity between seeds and eggs could be shown in a knowledge graph. Note that for the knowledge graph, I specifically state we’re talking about plant seeds and bird eggs.

I’ve mentioned in other blogs that knowledge is cache (a metaphor). Those analogousTo values were computed with relatively substantial effort (a call to an LLM) but we can cache that relationship and score in a knowledge graph for much cheaper lookups if anyone else ever asks.

Semantics, Analogy, Ontology, and Metaphor

Here is the TL;DR of a fun topic—a combinatorial comparison of four words that are often used interchangeably: semantics, ontology, analogy, and metaphor.

| Semantics | Ontology | Analogy | Metaphor | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Semantics | — | Focuses on meaning of terms vs. ontology’s formal entities & relations. | Semantics studies word/concept meaning; analogy maps relations between two domains. | Semantics is literal meaning; metaphor is figurative use of language to evoke imagery. |

| Ontology | Formal schema of what exists vs. semantics’ study of what words mean. | — | Ontology defines classes/relations; analogy links two ontologies or schemas by structural parallels. | Ontology is formal and declarative; metaphor is rhetorical and evocative, not intended for logic or inference. |

| Analogy | Analogical mapping uses relational patterns, whereas semantics focuses on individual word or symbol meanings. | Analogy crosses domain boundaries; ontology stays within a single modeled domain. | — | Analogy is logical mapping of structure; metaphor is poetic substitution without detailed structural mapping. |

| Metaphor | A metaphor leverages semantics to create vivid imagery, but semantics alone does not assert identity. | Metaphor is expressive language, whereas ontology is precise modeling. | Metaphor implies similarity for effect; analogy explicates similarity in steps or roles. | — |

With that cursory summary of the term comparisons, we’ll dive deeper into a few of those pairs.

Semantic vs Analogy

Towards the goal of employing AI to help us implement analogy into our analytics workflows, we need to distinguish between semantics and analogy. The reason is that there are two approaches, one involving vector embeddings and the other involving the full AI system. One is faster than the other.

Embeddings are numeric representations—arrays of numbers—that LLMs use to understand text. With OpenAI, each word or phrase becomes a 3072-number vector (using the text-embedding-3-large embedding model), and texts with similar meanings produce vectors that lie close together. The model works by converting your input into these vectors, updating them with context, and then using them to choose the next word. This lets the model gauge semantic similarity (how alike two pieces of text are), but it doesn’t capture deeper analogies or functional parallels. Embeddings tell you “what things mean,” not “how they’re analogous.”

To demonstrate, I first asked ChatGPT to create easily understood but abstract explanations for two well-known sayings:

- Prompt: Restate the following saying in abstract, domain-neutral terms—no metaphors, just the underlying principle: Still waters run deep.

- ChatGPT: The calmest or least conspicuous entities often possess the greatest depth or complexity.

- Prompt: Restate the following saying in abstract, domain-neutral terms—no metaphors, just the underlying principle: A bird in hand is worth two in the bush.

- ChatGPT: A certain, immediately available resource or opportunity is more valuable than a potentially greater but uncertain or unattainable one.

Next, I use Code 3, a Python script that creates vector embedding for the descriptions of our two sayings and computes a similarity score of the two.

import openai

from numpy import dot

from numpy.linalg import norm

openai.api_key = “Your OpenAI Key”

def get_embedding(text):

if not text:

raise ValueError(“text is required”)

resp = openai.Embedding.create(model=”text-embedding-3-large”,input=text)

return resp[“data”][0][“embedding”]

vec1 = get_embedding(“The calmest or least conspicuous entities often possess the greatest depth or complexity.”)

vec2 = get_embedding(“A certain, immediately available resource or opportunity is more valuable than a potentially greater but uncertain or unattainable one.”)

similarity = dot(vec1, vec2)/(norm(vec1)*norm(vec2))

print(“Cosine:”, similarity)

Code 3 — Python code to retrieve embeddings for text and compare similarity.

The answer returned is 0.2232649812954084. According to Table 3 below (created by ChatGPT), that score is “Minimal”. That doesn’t seem right—”Still waters run deep” and “A bird in hand is worth two in the bush” have very different meanings. I think there’s almost no similarity. But it’s not that bad of an answer.

| Range | Label | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| 0.00–0.10 | None | Practically no detectable semantic overlap; orthogonal concepts. |

| 0.10–0.30 | Minimal | Slight topical connection (e.g., shared common words) but distinct ideas. |

| 0.30–0.50 | Low | Noticeable thematic overlap (e.g., same broad subject area) but different focus. |

| 0.50–0.65 | Moderate | Seeming relationship in purpose or structure, though many differences remain. |

| 0.65–0.80 | High | Strong alignment in core concept and intent; usually analogies or close paraphrases. |

| 0.80–0.90 | Very High | Nearly synonymous or deeply analogous; only minor distinctions. |

| 0.90–1.00 | Near-Identical | Almost the same meaning or expression; interchangeable in most contexts. |

That “minimal” cosine score isn’t magic—it’s a side effect of how these embeddings are trained. Here’s why two very different proverbs like “Still waters run deep” and “A bird in hand is worth two in the bush” can end up at about 0.223 similarity:

- Both are generic proverbs. Embeddings often cluster common sentence-types together. Because each one is a short, familiar saying conveying a lesson, their overall “proverb-ness” pushes their vectors closer.

- Shared vocabulary and structure. Even though the key nouns (“waters” vs. “bird”) differ, both sentences use simple nouns + verbs + adjectives (“run deep,” “worth … in the bush”) in a similar grammatical pattern. That syntactic closeness boosts their cosine score.

- Surface-level semantics. Embeddings capture topical and stylistic overlap more than precise meaning. They’ve learned that proverbs about “hidden depths” and proverbs about “practical value” often appear in the same contexts (collections of sayings, advice articles, etc.), so their vectors gravitate together.

- Thresholds are heuristic. The “High” bucket for 0.6–0.8 is a loose guideline, not a guarantee of true semantic alignment. In practice, anything below around 0.85–0.9 for short, pithy sentences can still be misleading.

In short, the two sayings look similar to the model because they share the same genre, surface patterns, and contextual usage—even though their actual messages are worlds apart. Embeddings excel at grouping similar-looking text, but they can’t reliably distinguish nuanced meaning or opposing advice.

But there’s a parallel in how we compare ideas: vector embeddings can zip through millions of text snippets in milliseconds—ideal for brute-force similarity search in a vector database. They treat each chunk of text independently, stripping it of its surrounding context to boil it down to a fixed-length number array. That independence makes vector lookups blisteringly fast, but also means you lose the nuance that only arises when you see two passages together.

By contrast, asking an LLM to rate analogy or semantic similarity is slower and more costly in tokens, but far more accurate. The model can ingest both texts side by side, recall the wider conversation or domain, and reason through their relationships step by step. You get a fidelity of insight—understanding implied roles, causal chains, or stylistic subtleties—that raw embeddings simply can’t match.

In practice, there is a two-prong approach::

- Embed first to shortlist candidates (e.g. cosine similarity > 0.3) and cull the search space.

- Ask the LLM to compare only those few pairs directly, drawing on full context and logical mapping.

You retain the speed and scale of embeddings for broad filtering, then leverage the depth and precision of LLM reasoning for your final analogy scores—ensuring you never mistake mere semantic proximity for true structural insight.

Code 4 is a simple one-shot question and answer volley between me and ChatGPT (as opposed to a comparison of vector embeddings) on the similarity of the two sayings.

Me: On a scale of 0.0 through 1.0 what would you rate as the similarity between the metaphorical meaning of these two saying: “Still waters run deep” and “A bird in hand is worth two in the bush”

ChatGPT: I’d place their metaphorical‐meaning similarity very low, around 0.1 on a 0.0–1.0 scale.

- Still waters run deep speaks to hidden depth or unexpected complexity beneath a calm surface.

- A bird in hand is worth two in the bush urges valuing a sure thing over a risky opportunity.

They share almost no overlap in intent or imagery—one is about inner character, the other about risk vs. reward—so they fall into the “very low” similarity band (0.0–0.3).

Code 4 — Simple one-shot question to rate analogous similarity.

I very much agree with ChatGPT’s assessment. I’ve also tried a few other pairs of sayings and all of the answers from ChatGPT have been pretty good.

Simply measuring embedding vector proximity can miss the mark on nuanced meaning, whereas asking an LLM to compare the two sayings taps into its deeper language processing resources. Embedding cosine scores boil each sentence down to a point in high-dimensional space, so they’ll cluster any short, proverb-style phrases together even if their lessons conflict. In contrast, when you pose the question directly, the model draws on its learned knowledge of idioms, context, and purpose—it can explain that one proverb warns about hidden depths while the other values certainty over potential gain. In other words, embeddings give you a blunt statistical gauge of “textual likeness,” but a generative LLM query leverages semantic reasoning to tell you whether two ideas actually align.

When I compute the cosine similarity of the raw embeddings for two proverbs—say, “A bird in the hand is worth two in the bush” versus “A rolling stone gathers no moss”—I get a score like 0.2837. That number reflects only the “surface” overlap in wording and topical hints captured independently by each embedding, making it ideal for fast, large-scale searches in a vector database. But embeddings can’t look at two texts side by side or reason about their underlying structure: they simply measure how close each one lives in semantic space.

In short, embedding + cosine gives me a useful semantic similarity score, but LLM reasoning gives me a more faithful analogy score, because it encompasses the broader context and structural insight that embeddings alone can’t capture.

By contrast, when I ask an LLM to rate their analogy, it can compare them directly—mapping the lessons (“risk versus guaranteed reward” vs. “movement preventing buildup”) and judging how closely their relational structures align. That gives a more faithful analogy score, but it comes at the cost of higher token usage, API latency, and prompt-size limits if you try to batch hundreds of comparisons in one go.

This isn’t what we usually think of as “at scale”, but it works well if we have a few candidates to try. LLM prompts of embedding-based search, plus the depth and precision of LLM-driven analogy scoring—without busting your token budget or missing the structural insights that only a comparative prompt can reveal.

Just for kicks, let’s try a pair of sayings that are similar:

- Prompt: Restate the following saying in abstract, domain-neutral terms—no metaphors, just the underlying principle: Throwing caution to the wind.

- ChatGPT: Acting without regard for potential risks or negative consequences.

- Prompt: Restate the following saying in abstract, domain-neutral terms—no metaphors, just the underlying principle: Damn the torpedoes.

- ChatGPT: Proceed toward an objective while consciously disregarding known dangers or obstacles.

Running the Python code (Code 3) comparing the embeddings of the abstracted version of these two seemingly similar sayings, we get, Cosine: 0.5387756472784245 That’s a “moderate” score according to Table 2. The model that created the embeddings found the words in the two sayings to be found together. But that still is low.

Asking ChatGPT directly, this time it agrees with a 0.9 score.

Me: On a scale of 0.0 through 1.0 what would you rate as the similarity between the metaphorical meaning of these two saying: “Throwing caution to the wind” and “damn the torpedoes”

ChatGPT: I’d rate their metaphorical meanings at about 0.9 on a 0.0–1.0 similarity scale—both express consciously disregarding known risks in order to move forward.

Code 5 — Asking ChatGPT to measure analogous similarity between two like sayings.

I slightly disagree as the two sayings pretty much say the same thing—at least 0.95

Here’s a side-by-side comparison of how pure embeddings and a direct ChatGPT judgment rate two proverb-pairs—one with very different meanings and one with effectively the same meaning:

| Proverbs Compared | Actual (My) Interpretation | Cosine Similarity | Embedding Heuristic | ChatGPT Direct Rating | ChatGPT Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| “Still waters run deep” and “A bird in hand is worth two in the bush” | Different | 0.223 | Sort of correct: Minimal | 0.10 | Correct: Very low similarity |

| “Throwing caution to the wind” and “Damn the torpedoes” | Similar | 0.539 | Wrong: Moderate | 0.90 | Correct: Very high similarity |

The bottom line is, when comparing the similarity between two pieces of text, we can compare two embeddings or ask ChatGPT. If we create embeddings for each saying and store the embeddings in a vector database, we can find the closest match fairly easily (using the vector database’s innate search capability). However, there is a higher chance the answer will be wrong it the two texts are analogously different.

For a more reliable measure of analogous similarity, asking ChatGPT is much more compute intense (thus expensive and will run longer), although the answer is more likely to be correct. However, once we have the score, we can store the score—for example, caching the knowledge as an analogousTo relationship of a knowledge graph, as discussed earlier.

Within the Universe of Training

If LLMs can produce such fine analogies between pairs of sayings, what prevents them from conjuring up profound analogies that can be the first step towards a solution to truly novel problems? That is, problems that have not yet been encountered. That last sentence is really the answer—it’s not in the LLM’s training material, it’s space of knowledge.

It’s important to keep in mind that the sayings we just discussed are well-known. Much has been written about them, so much of it is in the LLM’s training data. Thus, ChatGPT is familiar with them—it didn’t really reason about the analogy on its own. Somewhere within the LLM’s terabytes of training material, there is at least an inkling of connection for an analogy and perhaps even take a seeming “magically” slight leap—at best.

The previous paragraph encapsulates the primary thesis of this blog and even much of Enterprise Intelligence. That is, solutions are produced within a knowledge space which defines a space of possibilities. For example:

- A person: All that the person was taught and experiences—some consciously registered, some unconsciously registered.

- An enterprise: All that is captured in all databases, documentation, and all the skill, experience, and insights within the heads of all employees (tribal knowledge).

- All of Humanity: All that is encompassed by all people, and all that has been recorded by all people.

- An LLM (at the time of this writing): All the training material, which is mostly a subset of the knowledge space of humanity—primarily publicly available writings. But as comprehensive as the training material might be, it’s a sterilized version of abstracted symbols converted from the original Thousands of Senses tied to all the context from which the human experiences were born.

- The Universe: All that has happened and all that will happen.

Analogy is the discovery of similarity between two disparate patterns within a knowledge space. Through analogy, a novel problem could still be within the space of possibility of a knowledge space. When a person encounters a truly novel problem, the person can hopefully draw an analogy that inspires a solution, or at worst, learn something to build their knowledge space.

Similarly, the knowledge space of earlier LLMs (ca. 2022 through 2023) were limited to their training data. Today, ChatGPT, Grok, etc. can access Web sources to supplement itself with data outside of its training data.

So, given a truly novel problem—not two well-known sayings—finding an analogy will require massive probing in the dark. That’s what I do when I have to deal with a terribly un-Google-able bug: take long walks probing the depth and breadth of the knowledge space in my brain for all sorts of situations. Fortunately, those walks (or sleeping on the problem) usually resulted in magically finding the solution.

As mentioned, an analogy is the similarity between two disparate patterns. There is an identified chasm, but at least we know what chasm we’re trying to cross. So when we presented two sayings to the LLM, the solution space is much smaller than presenting only our novel solution, we don’t even know where the chasm is.

Metaphor vs. Analogy

Metaphors jump straight across domains by saying “X is Y,” sparking an image or emotion without spelling out how they actually match—think “time is a thief.” Analogies, on the other hand, lay out the parallels step by step—“time is to life as a river is to a boat”—mapping roles and relationships so you can reason from one field to another.

Both tools compare one thing to another, but they serve different purposes.

- Analogy is a teaching hack. It lines up two things that share a pattern and walks you through the match, making complex ideas click. “A heart is like a pump” shows you how blood moves by comparing it to something you already understand. Use analogies when you want to break down a new concept into familiar pieces.

- Metaphor is a creative shortcut. It equates two things—no “like” or “as”—to paint a vivid snapshot or stir a feeling. “The world is a stage” isn’t literally true, but it captures the drama of daily life in a single phrase. Reach for metaphors when you want color, flavor, or an emotional hit.

| Type | Phrase | What It Shows |

|---|---|---|

| Analogy | “A computer is like a librarian who quickly finds and organizes information for you.” | Maps roles (computer vs. librarian) and actions (searching/indexing vs. cataloging) to clarify function. |

| Analogy | “Mu Shu pork is like a Chinese burrito.” | Aligns structure (wrapper, fillings, eating style) to explain a foreign dish via a familiar one. |

| Analogy | “Managing a team is like conducting an orchestra.” | Aligns roles (musicians vs. team members) and timing (notes vs. tasks) to explain leadership dynamics. |

| Metaphor | “Shiatsu massage is like a dentist visit to pull a tooth.” | The pain is intense, but we’ll feel better later. |

| Metaphor | “That contract was a ticking time bomb.” | Evokes looming danger and urgency without a literal bomb. |

| Metaphor | “You’re the Kramer of the group.” | Compares someone’s eccentric, energetic presence to the iconic sitcom character from Seinfeld. |

Analogy: Knowledge Graph ⇄ Dimensional Model

For the Business Intelligence audience, saying “a knowledge graph is like a dimensional model,” is a metaphor, as we’re invoking a surface likeness without spelling out the one-to-one mappings.

If you want to turn it into an analogy, you’d lay out the structural correspondences, for example:

| Knowledge Graph | Dimensional Data Model |

|---|---|

| A web of linked ontologies: classes, properties, and instances connected by explicit RDF/OWL relations. | A collection of linked star schemas: fact tables surrounded by dimension tables connected via keys. |

| Ontologies capture real-world entities and their rich, extensible relationships. | Star schemas capture business events and their descriptive attributes. |

| Designed for semantic queries, inference, and flexible schema evolution. | Designed for analytical queries, aggregations, and predictable performance. |

| Relationships are first-class objects, enabling reasoning over graph-traversals. | Relationships manifest as foreign keys, enabling SQL joins and OLAP drill-down. |

| SPARQL graph traversal | SQL |

In both cases you’re building a comprehensive view—whether by weaving together ontologies in a graph or by joining star schemas in a warehouse—but the knowledge graph emphasizes semantic richness and inference, while the dimensional model emphasizes analytical performance and aggregations.

That step-by-step mapping—ontology class ↔ dimension table, triples ↔ fact rows, edges ↔ FKs, etc.—is an analogy, because it shows precisely how the two models align in structure and function.

In a nutshell, analogies explain by mapping structure, while metaphors enliven with imagery.

Metaphor versus Ontology

please provide examples of what is metaphorically and ontologically similar to sharks.

Code 6 — Prompt to ChatGPT.

Metaphorical Similarities

In language and culture, “shark” often stands in for aggressive, predatory, or top‐tier actors. Metaphorically similar figures include:

| Metaphor | Description |

|---|---|

| Loan Shark | A predatory moneylender charging exorbitant interest rates |

| Shark Investor | An aggressive venture capitalist negotiating high-stakes deals |

| Shark in the Pool | A dominant competitor who outclasses all others in a given arena |

| Litigation Shark | A ruthless lawyer or firm that overwhelms opponents with costs |

| Card Shark | A highly skilled (often unscrupulous) gambler exploiting others |

Ontological Similarities

Strictly speaking, “ontologically” similar creatures share key biological or ecological characteristics with sharks:

| Group | Similarity |

|---|---|

| Great Blue Shark’s Other Conspecifics | Species like the mako, hammerhead, and tiger shark share similar physiology and predatory roles. |

| Rays & Skates | Cartilaginous fish (Class Chondrichthyes) with similar skeletons and skin textures. |

| Sawfish & Guitarfish | Close relatives within the same subclass, sharing flattened bodies and electroreception. |

| Orca (Killer Whale) and Saltwater Crocodile | Apex marine predators with comparable hunting strategies and top-of-food-chain status. |

Example

Let’s play with a business-oriented example. We’ll test an LLM’s (ChatGPT o4-mini) ability to score the analogous similarity between a few business processes in two ways: using business process sequences (Code 7) and with a natural language text summary (Code 8).

Dental Visit

arrive->checkin->provide insurance->seated->called in-> sit in chair->assistant preps->dentist anesthesia->wait->start procedure->end procedure->assistant clean up->leave chair->checkout->set followup->leave

Restaurant Meal

arrive → greeted → seated → intro → drinks → order → served → dessert → charged → bigTip → paid → leave

Gym Visit

arrive → check in at front desk → change into workout gear → warm up → perform workout sets → rest/recover between sets → cool down/stretch → shower and change → log workout session → leave

Job Inteview

post job → collect applications → screen resumes → phone interview → take-home assessment → on-site interview → debrief team → extend offer → negotiate terms → candidate accepts → prepare onboarding → new-hire orientation → complete probation → full integration

Pacemaker Implant

arrive → check in at front desk → provide insurance → pre-operative assessment → ECG and vitals monitoring→ prep surgical suite → administer sedation/anesthesia → make incision → insert leads → place pulse generator→ intraoperative testing and programming → suture incision → apply sterile dressing → transfer to recovery

→ post-operative monitoring → discharge planning and checkout → schedule follow-up appointment → leave

Code 7 — Sequences from sample processes.

Code 8 list five processes, each described in a single paragraph of prose—focusing on what the process is for, rather than how it unfolds step by step. These should embed into very different regions of semantic space than the “step-by-step” workflows of Code 7.

Restaurant Meal

A restaurant meal is an experience designed to nourish the body and delight the senses by guiding guests through a curated sequence of flavors, aromas, and atmospheres. From the moment diners arrive, the establishment’s goal is to create a welcoming ambiance, introduce them to menu highlights, and anticipate their preferences—whether with a signature appetizer, a perfectly timed drink refill, or a chef’s special suggestion. Beyond simply serving food, the process aims to craft lasting memories: attentive pacing, thoughtful presentation, and gracious farewells that leave patrons eager to return for another exceptional evening.

Gym Workout

A gym visit exists to empower individuals in their pursuit of health and strength by providing a supportive environment, tailored guidance, and clear measures of progress. It brings members into a space equipped for safe, effective exercise; it offers warm-ups that prepare mind and body, instruction that refines technique, and tools that track every lift, step, or rep. Ultimately, the process is about more than burning calories—it’s about instilling confidence, building resilience, and reinforcing the habit of personal growth through measurable, repeatable challenges.

Dental Checkup

A dental checkup is a preventative care ritual aimed at preserving oral health and preempting future complications by combining professional assessment, targeted cleaning, and patient education. It reassures patients through expert examination—detecting early signs of decay or gum issues—while employing gentle, precision cleaning techniques to remove buildup and polish enamel. The overarching purpose is to maintain a lifetime of healthy smiles, minimize the need for invasive treatments, and foster habits that contribute to overall well-being.

Job Interview

A job interview is a structured dialogue intended to identify the best match between a candidate’s skills, aspirations, and values and an organization’s needs, culture, and long-term goals. It brings together hiring managers and applicants in a series of conversations—some testing technical prowess, others probing problem-solving styles or leadership qualities—with the aim of uncovering true potential rather than just polished resumes. Ultimately, it seeks to create a partnership that fulfills both parties’ objectives: the company gains capable talent, and the individual secures a role aligned with their growth path.

Pacemaker Implant

A pacemaker implant is a life-restoring medical procedure whose purpose is to ensure a patient’s heart maintains a steady, appropriate rhythm when its natural conduction system falters. Beyond the surgical insertion of electrodes and a pulse generator, the process encompasses comprehensive pre-operative evaluation, precise device programming, and meticulous postoperative monitoring. The ultimate goal is to give patients lasting cardiovascular stability—improving quality of life, reducing symptoms like dizziness or fatigue, and preventing dangerous arrhythmias.

Code 8 — Unabstracted descriptions created by ChatGPT based on the sequences shown in Code E.

For each pair of these processes, provide a score from 0-1 (based on the scale also provided) that measures how analogously similar the pair of processes are (analogous is different from semantically):

Code 9 — Instruction prompt prepended to Code 7 and Code 8 before submitting to ChatGPT.

Table 9 is the result returned by ChatGPT of the comparisons between the processes listed in Code 8. The scores are the same as Table 3. Remember, the scores represent how analogously similar they are. For example, the process of serving a restaurant meal obviously isn’t the same as your gym workout routine. But there are analogous elements (if you squint enough—an interesting metaphor).

| Process | Sequence-OpenAI Embedding | Sequence-ChatGPT | Description-OpenAI Embedding | Description-ChatGPT | My Score of Analogous Similarity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Restaurant Meal ↔ Gym Workout | 0.5005 | 0.5 | 0.4053 | 0.65 | Low |

| Restaurant Meal ↔ Dental Checkup | 0.5749 | 0.6 | 0.2653 | 0.70 | Moderate |

| Restaurant Meal ↔ Job Interview | 0.3949 | 0.3 | 0.3110 | 0.50 | None |

| Restaurant Meal ↔ Pacemaker Implant | 0.4600 | 0.2 | 0.2340 | 0.20 | Minimal |

| Gym Workout ↔ Dental Checkup | 0.4926 | 0.6 | 0.3020 | 0.70 | Moderate (haha) |

| Gym Workout ↔ Job Interview | 0.3851 | 0.3 | 0.2692 | 0.45 | None |

| Gym Workout ↔ Pacemaker Implant | 0.5641 | 0.3 | 0.2522 | 0.45 | Minimal |

| Dental Checkup ↔ Job Interview | 0.3935 | 0.35 | 0.2533 | 0.35 | None |

| Dental Checkup ↔ Pacemaker Implant | 0.6210 | 0.8 | 0.2872 | 0.75 | Moderate |

| Job Interview ↔ Pacemaker Implant | 0.3600 | 0.3 | 0.2328 | 0.30 | Minimal |

Figure 2 is a small sample of what the analogous relationship and score would look like in a knowledge graph.

Table 10 lists the ChatGPT’s justifications, in its own words, for the analogous similarity score for each combination of processes, based on the sequence and description.

| Process Pair | Seq-ChatGPT | Seq Justification | Desc-ChatGPT | Desc Justification |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Restaurant Meal ↔ Gym Workout | 0.50 | Shared structure: arrival → prep (gearing up/greeting) → core activity → cleanup/checkout → leave | 0.65 | Both describe a guided, multi-stage experience with prep, main action, feedback/serving, and closure |

| Restaurant Meal ↔ Dental Checkup | 0.60 | Service interaction: arrival → seating → expert service → payment → leave | 0.70 | Service ritual: expert guidance, comfort measures, follow-up recommendations, and closure |

| Restaurant Meal ↔ Job Interview | 0.30 | Sequence similarity: introductions and evaluations, but domains differ (food vs hiring) | 0.50 | Both are structured sequences with intros, assessments, and outcomes, though one is culinary and one is professional |

| Restaurant Meal ↔ Pacemaker Implant | 0.20 | Only arrival and exit align; core actions and stakes diverge sharply | 0.20 | Marginal overlap: one is guest service, the other is critical medical procedure, sharing little beyond check-in and discharge |

| Gym Workout ↔ Dental Checkup | 0.60 | Preparation → expert-led procedure → cleanup → exit (change/shower vs chair exit) | 0.70 | Health-focused ritual: warm-up/exam, professional intervention, cleanup, and aftercare |

| Gym Workout ↔ Job Interview | 0.30 | Both have a “warm-up” or screening phase followed by main activity and wrap-up, but contexts differ | 0.45 | Both involve preparation, core performance/assessment, and closure, though one is fitness-oriented and one is evaluative |

| Gym Workout ↔ Pacemaker Implant | 0.30 | Prep → main intervention → recovery/cool-down → exit | 0.45 | Sequence of preparation, core action, monitoring/recovery, and discharge is common, despite different domains |

| Dental Checkup ↔ Job Interview | 0.35 | Screening/exam vs resume screening/interview; both involve evaluation and decision points | 0.35 | Both describe an evaluative process: assessment, feedback, and next-step recommendation |

| Dental Checkup ↔ Pacemaker Implant | 0.80 | Both are medical procedures: check-in, anesthesia, procedure, cleanup, follow-up | 0.75 | Medical context: expert prep, life-critical intervention, post-procedure monitoring, and aftercare |

| Job Interview ↔ Pacemaker Implant | 0.30 | Screening and selection vs pre-op evaluation and selection for surgery | 0.30 | Both involve evaluation phases leading to a “go/no-go” decision and subsequent action |

Which Score Should We Use?

Table 9 above shows for similarity scores: Sequence Embedding, Sequence ChatGPT, Description Embedding, and Description ChatGPT. When should I use any of these?

This question gets to the heart of the problem this blog addresses. That is: I have a whacky idea for a wild and likely unprecedented enterprise, but have no idea what it will look like.

Since the company is probably unprecedented, I can’t simply Google for similar companies to model my idea after. In fact, the reason I’d still be pursuing my whacky idea is that I did Google it and nothing like it showed up. At this point, I know my company is novel and thus will come with a competitive advantage.

We know what we want our new enterprise to do, but we don’t know anything about the processes, I need to form ideas about what it will look it. Like anything we invent, what are the parts and how are the parts organized into processes?

Since all I have is a description of what I intend to build, I can only search for something that analogously seems to do the same thing. Remember, I don’t know what the processes look like, so the two sequence comparison scores (Sequence Embedding, Sequence ChatGPT scores) are eliminated in this situation.

I can search my knowledge graph of nodes which can include nodes identifying other companies, machines, ecosystems, etc. For example, the five businesses listed in Code 8 above each will have a node in the knowledge graph along with an attribute of the description.

If my knowledge graph were that simple, the best choice would be to submit ask the LLM for each pair of the description of my idea versus the description of each of the five businesses (Description ChatGPT score). That approach seemed to return the scores that looked the most accurate. That will take perhaps four to fifteen seconds total.

With those deemed at least moderately analogous, I could look at the processes of the sequences for inspiration of the processes to invent for my new idea.

However, my knowledge graph likely contains thousands, if not billions, of nodes describing something. That would take quite a while! So that brute force approach will not work well. So, we can sacrifice accuracy for speed by using the embeddings approach (Description embedding). Although the scores comparing description embeddings versus the descriptions using an LLM will probably not be as good, it will be much faster (especially using an enterprise-class vector database such as Pinecone).

At this point we have a limited list of analogous possibilities for our new idea. Because the embedding scores are probably not as accurate, we will have quite a few “false positives”. We could whittle away the number of false positives by asking an LLM for its opinion on this limited list.

With a nice list of candidate analogies, we can study the attributes, particularly processes (as shown in Figure 2 above). Those processes of the candidate analogy are seeds the ideas from which we can evolve for our new idea. Many will whither and die, but a few might flourish into a fully-formed business model of our new idea.

That’s pretty much the same process our brain uses to invent novel solutions to novel problems—minus the knowledge graphs, LLMs, and vector databases. What I just described—and note this topic itself is an analogy—is computationally intense, but original thinking is so hard, it first requires sentience and then a brave soul to persevere.

Trying it Out with an LLM

Let’s try this out. Code 10 is an LLM prompt that include the instructions to think “analogy”, the scale, the two descriptions we’d like to measure, and an example of the format of the result.

On a scale defined as follows, how analogous are these two processes in terms of their relational structure and functional stages? Ignore surface wording—focus only on roles, phases, and transitions.

AnalogyScale = {“0.00–0.10”: “No analogy”, “0.10–0.30”: “Minimal analogy”, “0.30–0.50”: “Low analogy”, “0.50–0.65”: “Moderate analogy”, “0.65–0.80”: “High analogy”, “0.80–0.90”: “Very high analogy”, “0.90–1.00”: “Perfect analogy”}

ProcessA: “miner’s lettuce farm to sell at farmer’s market”

ProcessB: “Business intelligence presentation-AI on top of a solid BI foundation”

Return only a JSON object with two keys:

- “score”: a number between 0.0 and 1.0

- “justification”: one sentence explaining the key structural similarity or difference

Example output:

{ “score”: 0.72,

“justification”: “Both processes follow the same five-phase progression of intake, preparation, core delivery, transaction, and conclusion despite different domains.”

}

Code 10 — Prompt template to LLMs.

I presented the prompt to three LLMs: ChatGPT, Grok, and Copilot. All three correctly returned the result in the JSON format I requested. Table 11 shows the results. Again, the scores are as per Table 3.

| LLM | Score | Justification |

|---|---|---|

| ChatGPT o4-mini | 0.58 (Moderate) | Both begin with gathering raw inputs (cultivating lettuce vs. collecting and modeling data), proceed through a transformation phase (harvesting and packaging vs. AI-enhanced analysis), and end with delivering a refined product to end users. |

| Grok 3 | 0.30 (Low) | Both processes involve preparation and delivery of a product or service to a target audience, but ProcessA focuses on tangible production and market sale, while ProcessB emphasizes data analysis and presentation. |

| Copilot | 0.68 (High) | Both processes involve foundational setup, development of a core product, enhancement through added value (lettuce quality or AI layer), and final delivery to a target audience. |

I mostly agree with Grok 3. I can see ChatGPT’s point of view. I disagree with Copilot. But all of the justifications seem plausible to me. The range of responses from the three LLMs is very intriguing—reminiscent of the varying opinions of people—very cool.

Analogous and Semantic Similarity Score Combo

Let’s take it a step further and demonstrate how to compare our whacky idea to business descriptions in our knowledge graph. Code 11 is a description of our business idea, for which we have no idea how to implement.

Venus & Cheddar Animal Rescue

Our organization is dedicated to rescuing and relocating animals trapped in conflict zones, providing each rescued animal with safe passage, medical care, and new homes free from the threat of war. Through a global network of local partners—veterinarians, shelters, and trusted field operatives—we identify at-risk dogs, cats, and wildlife, secure necessary permits, and arrange fully funded transport corridors by land, air, and sea. Every step—from emergency veterinary stabilization and temporary sheltering to flight-ready crates, flight charters, and destination intake—is covered by our donor-supported funding model. By coordinating with relief agencies, governments, and animal-welfare advocates, we ensure that each animal arrives healthy, vetted, and ready for adoption or sanctuary placement, transforming the chaos of war into a journey toward safety and renewed hope.

Code 11 — Whacky business idea.

Referring back to the five descriptions provided in Code 8, let’s compare them to this whacky business idea laid out in Code 11.

But first, I’d like to toss out the idea of providing the analogy score as we did before, but additionally an “LLM-generated Semantic Score”. In this case, by “semantic”, I don’t mean in the same context of the vector embedding. I mean, for example, that if I had a description for an eye doctor checkup, it’s probably analogously similar to a dental checkup but also quite semantically similar because they are both specialty routine healthcare procedures. On the other hand, a car detail process (full-service car wash, wax, etc.) could be analogous to a dental cleaning, but semantically different.

Code 12 is a prompt we can present to an LLM. But before posting Code 12, append the five business descriptions from Code 8 and the description of Venus and Cheddar from Code 11.

For each pairing of “Venus & Cheddar Animal Rescue” with the other five processes I previously provided, assign:

- an Analogy Score (0.0–1.0) based on how closely their abstracted relational structure and functional stages align,

- an LLM-generated Semantic Score (0.0–1.0) based on how closely they share the same domain or context, For example, a dental office visit is semantically close to a visit to the dermatologist.

and provide a one-sentence justification for each score.

Return in this format:

| Process Pair | Analogy Score | LLM Semantic Score | Analogy Justification | LLM Semantic Justification |

|---|

Code 12 — LLM Prompt for comparing business descriptions to Venus and Cheddar.

Table 12 shows the result from ChatGPT. Notice how both scores for Pacemaker Implant (first row) are on the higher side. That might imply that Pacemaker Implant is less valuable as a surprisingly insightful analogy since they are rather semantically close, therefore rather obvious and not so imaginative.

| Process Pair | Analogy Score | LLM Semantic Score | Analogy Justification | Semantic Justification |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Venus & Cheddar Animal Rescue ↔ Pacemaker Implant | 0.85 | 0.70 | Both are life-saving medical operations with stages of assessment, intervention, monitoring, and follow-up, differing only in domain specifics. | Both fall under healthcare interventions—one veterinary, one human—with similar regulatory and clinical contexts. |

| Venus & Cheddar Animal Rescue ↔ Dental Checkup | 0.78 | 0.65 | Each involves intake, stabilization/cleaning, core treatment, discharge planning, and follow-up, mapping step-by-step. | Both are preventive/curative care processes in clinical settings with patient/examiner roles and hygiene focus. |

| Venus & Cheddar Animal Rescue ↔ Restaurant Meal | 0.72 | 0.30 | Both guide beneficiaries through welcome, core service, transaction, and send-off phases, though one serves food and one transports animals. | Both are service experiences with guest/customer interactions, but healthcare vs. hospitality makes them semantically distant. |

| Venus & Cheddar Animal Rescue ↔ Gym Workout | 0.65 | 0.30 | Each provides a staged experience—entry, preparation, core activity, tracking, and exit—with analogous structure despite different goals. | Both involve scheduled visits and service delivery, but fitness training versus animal care yields low semantic overlap. |

| Venus & Cheddar Animal Rescue ↔ Job Interview | 0.60 | 0.20 | Both assess candidates (animals vs. people), guide them through evaluation and selection, and culminate in placement, but differ in specifics. | Hiring and animal rescue share structured evaluation workflows, but one is talent acquisition while the other is care logistics—very different domains. |

However, the Restaurant Meal pairing scores high on analogy but remains semantically distant—making it a fertile source of surprising, cross-domain inspiration rather than an “obvious” parallel.

Conclusion: Curiosity, Delayed Gratification, and the Goodness of the Bad Old Days

This completes the trilogy of blogs addressing the justification for Time Molecules, a book all about a “data warehouse” of hidden Markov models (which is a web of Markov Models linked with a web of correlations). The world we experience is made up of interacting processes that are constantly morphing each other. And any solution we devise is itself a process. Therefore, a systems and process-centric BI foundation provides a higher order of analytical information.

All processes are the primal DNA for some sort of solution. When faced with a novel problem we can discover a novel solution that begins with something that just resembles what we might have seen before or just heard about—a metaphor or analogy. From there, that seed of a solution rapidly evolves into a novel solution for our novel problem.

My proposition is that as Wikidata is a vast integrated knowledge graph across all subjects and domains, the Time Molecules database of hidden Markov models should include processes well beyond what seems even remotely related to our enterprise and/or interests. Appropriately, we could express this in the analogy: Wikidata is to knowledge graphs as Time Molecules is to Bayesian networks.

But this blog trilogy isn’t just about Time Molecules itself. It’s a reminder of our mindfulness on critical, creative, and original thinking as the alluring mana of AI encroaches on our lives. Forget AGI or ASI (artificial General or Super intelligence). Today’s AI is smart enough to be dangerous (that’s a metaphor). To preserve those advanced thinking skills, we must—like a chess master plotting several moves ahead to secure checkmate—always envision the end-game and think in terms of the steps it will take to get there (that’s an analogy).

Let’s continue on with what might appear to be a gratuitously analogy-laden conclusion. But I think that’s just because analogy and metaphor are what we’ve been talking about. I didn’t purposefully include analogies for the sake of more analogies. Go read anything else and count how many analogies and metaphors there are. You’ll see there is much more to analogy and metaphor than philosophical mumbo jumbo—they’re embedded deep into our thinking processes.

Curiosity

The drive to find an idea to solve a nagging problem can be as powerful as hunger after a long hike without enough food. The intensity of the drive is mostly beyond our control that is satiated only with a meal or at least a seed of hope hidden in what caught our curiosity.

I personally don’t think the sort of curiosity that catches your attention is completely random. I think there’s some problem in the background of your mind that spotted something from which some imagination can yield a solution.

At the heart of every creative leap lies a mix of primary drives—curiosity, hunger, and the rest—that act like built-in programs, each honed by our unique life experiences into a personal lens for what we notice and pursue. Curiosity urges us to probe the edges of our knowledge; hunger channels us toward whatever promises reward. It’s the peculiar blend of these motivations, sharpened by our context, that shapes which analogies we’ll spot and how we’ll frame every question.

We could bolt “innate drives” onto AI, but without the rich backdrop of history and emotion they’d feel dry and out of sync—outsiders peering at the world through lenses they can’t truly wear. Today’s systems follow patterns; they don’t decide what matters. If we elevate motivation itself to a first-class event—tracking its surges and slumps alongside collisions, thresholds, and other processes—we can begin to craft machine intelligences that not only map procedural paths but care deeply which ones to follow.

Delayed Gratification

I began my programming career in 1979. The bad old days. I plodded through the “bad old days” of the 1980s and early 1990s, needing to write my own database engines, various parsers, or even resort to assembly language to write optimized routines—for each client and a number of different coding languages.

Curiosity drove my ability to endure the 10+ hour days of coding it took to write it with just a text editor (think programming in notepad). As it is today, I couldn’t simply take code from one customer to another. Even if I could, chances are the next customer used a different, incompatible system. But at least today, valuable code snippets are generously online in forums, Github, and now AI can provide more than handy snippets. I had to rewrite code mostly from memory for every customer I was assigned to. But there was a bright side. Each new customer was like a new version of the code. I was able to apply lessons learned and streamline my coding.

From those bad old days, the first fifteen years of my career, I also collected a very deep pool of experiences—mistakes, gotchas, quirks at each customer, quirks of different versions of C++ and other languages. Wherever I worked after that, tough, un-Google-able problems (meaning no one posted anything about it for Google to find), I was able to find some analogy towards a solution from that pool of pain.

The atrophy of human agency—critical thinking, and original creativity—moved upwards a couple of decades ago, well before this current AI era of LLMs (ChatGPT in Nov 2022). Back in the mid to late 1990s, Web search engines and online forums came online and evolved to what they are today. The likes of Stackoverflow, Reddit, and a plethora of blogs sites and YouTube channels made it fantastically easy to find community-boosted solutions posted by experts of just about any field.

Those resources are wonderful, and I used them all the time. Over the years, those resources saved me countless hours of drudge work figuring out simple code, studying approaches, and working through annoying bugs in third-party software. But by the time such resources became mainstream, I had been a software developer for about 20 years, so coding was already deeply engrained in me.

Relying on those resources at the level of the late 1990s though early 2020s didn’t impinge on my critical thinking skills—that is, my ability to apply my own experience and insights to fairly novel and complex projects. The critical thinking of software development was already well-baked in my head. I still had to design and write most of the code. I just didn’t spend hours working through tons of idiosyncrasies in the operating systems, third party software, or the development environment itself.

However, those skills atrophy the moment we rely on it as the primary or even sole source of knowledge. Just as a pilot who relies mostly on autopilot loses precious practice time, a coder who lets AI write every line of code loses the muscle memory and judgment needed to supervise it. I hear it said that human coders will still be needed to oversee the AI-generated code. But how can human coders acquire the skills to oversee coding when it takes thousands of hours of actual work to be a seasoned coder?

That’s why the three parts of this blog series form a vital prescription:

- From Data Through Wisdom shows that raw data alone can’t build understanding.

- Thousands of Senses argues that we must expand our perceptual and conceptual toolkit to catch the subtle signals AI might miss.

- Analogy & Original Thinking drives home how to weave those signals into genuinely new ideas—so that when we face novel challenges, we don’t default to the nearest AI suggestion but instead spark our own insights.

Relying too heavily on AI is like living on fast food: it feels ultra-satisfying in the moment, but over time it leads to mental obesity. Losing weight is tough, and relearning how to think critically and rebuild domain wisdom is a few times harder (I know!). But it’s nothing compared to the Herculean effort required to reclaim lost agency once it’s handed over to whatever “higher power”. We must treat our minds tougher than just ordinary muscles: exercise them daily, challenge them relentlessly, and never let AI become a crutch. Use AI as an amplifier, not a substitute—keep flying the plane, writing the code, and forging your own path, because genuine human agency and wisdom don’t regenerate overnight.

Running Towards Your Human Agency

Our consciousness is forged from a lineage of billions of years of evolution—and I’m very sure there’s some secret sauce to consciousness we haven’t yet been able to pursue (beyond neurons and all its supporting mechanisms, something emergent or even beyond “natural”)—within the rough and tumble context of the world in which all life evolved, and our interactions with everyone we’ve encountered. By “Everyone we’ve encountered”, I mean everyone, since the influences of everything we know today can be connected (like the so-called “six degrees of separation”) to pretty much every human that has existed.

All of that heritage is a different issue from whatever agency there is of AI today. Surely, AI, as it is with all our creations, is a part of us since we built it and it’s trained on the corpus of humanity’s writings—at least public writings. But it’s also devoid of the cascading countless intricate connections that are sterilized when we abstract the full richness of real-life experience for the symbols of language.

You cannot fall into the trap. The vast majority of people will because the convenience and pragmatism (pragmatism, meaning practical, immediately actionable) of immediate gratification is incredibly seductive. Maybe the cause is already lost. However, the path of delayed gratification forges mastery, your own solid inner systems from which you add your unique value. There’s still time to find and claim your unique spot in this new world! Don’t get caught in AI’s gravity well where there will be no escape.

From what I’ve laid out in Enterprise Intelligence, Time Molecules, the Prolog in the LLM Era blog series, and this blog trilogy, run with it. Take it somewhere in all the countless directions beyond what lies at “the race to the bottom” from all-encompassing LLMs. To paraphrase one of my wife’s favorite watercolor artists says, “I give you artistic license”. There is another favorite who said, “stay a mile ahead”.