Welcome to the Prolog in the LLM Era Summer Vacation Special! Starring … Prolog … knowledge graphs … ChatGPT o4-mini … neuro-symbolic AI … and our special guest … Thinking Fast and Slow!

In this episode (Part 11 of the series), I wish to address how neuro-symbolic AI relates to this series. After all, the series title, Prolog in the LLM Era, includes a symbolic side (Prolog) and a neuro side (LLMs are at their heart a neural network).

The title of this blog is a riff on the title of Daniel Kahneman’s book, Thinking Fast and Slow, from which the notions of System 1 and System 2 were popularized. The relevance of Kahneman’s book to this blog is the difference in the way the neuro-symbolic AI folks map to System 1 and System 2 (neural networks and some rules-based system, respectively) to how I mapped it in the pilot episode of this series, Prolog’s Role in the LLM Era – Part 1.

Spoiler alert: Since most of the AI technologies are capable of answering questions very “fast” (at least to our human sense of what “instant” seems like), the issue isn’t fast or slow, but the quality of the question it’s facing. Some questions are very easy to answer, because there is a direct and very highly probable answer. Some questions are novel, clearly wrought with imperfect information, and/or complex and thus require iterative analysis.

For example, “What is the capital of Hawaii?” There is a direct, unambiguous answer for that question. Capitals of places is such a generalized question that chances are, the answer is easily answered by comprehensive and well-curated knowledge graphs such as Wikidata or Google Knowledge Graph. So the answer is a matter of a very simple SPARQL query as shown in Figure 1.

Note the query was correctly answered, Honolulu, and it took an incredibly fast 115 ms!

Or a Prolog query to a comprehensive Prolog base would look something like: capital(hawaii, X). That would probably be implemented in a Prolog base as a direct fact and thus fast.

On the other hand, the chances are that the following question isn’t in publicly available knowledge graphs: “What is the most endangered endemic species in terms more sophisticated than mere population level of Hawaii?” Chances are that a SPARQL query like the one in Figure 1 will return nothing, if we could even construct such a query in SPARQL.

Sidenote: SPARQL is not a reasoner in the way Prolog is. In the Semantic Web, SWRL adds rule-based reasoning by combining OWL with a simple rule language. It lets you define logical rules such as, “if a person has a sibling who is male, then they have a brother.” Just as SPARQL is to SQL, SWRL is to Prolog—a more constrained version adapted to the Semantic Web’s structure and reasoning model. Unlike Prolog, which supports full logic programming with recursion, unification and backtracking, SWRL is limited to simple if-then rules and depends on OWL reasoners such as Pellet or HermiT, which limits flexibility and performance at scale.

But a call to ChatGPT will at least return what most would consider at least a “highly educated guess”. I asked ChatGPT o4-mini. I watched it go through iterations of questions (presumably to itself) and returned a long, comprehensive answer. It says it “Thought for 19 seconds”. Code 1 shows the “summarization” portion of the answer.

Bottom Line:

If you measure endangerment by geographic range, rate of decline, fragmentation, phylogenetic uniqueness, or genetic viability, the ʻAkikiki stands at the very top of Hawaii’s most critically imperiled endemics. Its combination of an ultra-small, shrinking habitat footprint and vanishingly low wild numbers goes far beyond what a simple population count can convey.

Code 1- ChatGPT response from my complicated question.

Just for kicks, I also asked ChatGPT o4-mini, the direct question: What is the capital of Hawaii?

Figure 2 shows it answered in much less that a second.

Figure 2 – Asking ChatGPT a very simple and direct question.

So, one of the leading LLMs at the time of writing, a multi-billion dollar asset, is able to answer a direct, deterministic question fast. And it answered a creative, non-deterministic, and complicated question slow, but still relatively fast. How long would it take even a team of PhD humans armed with the Internet to cobble that together?

Table 1 compares how System 1 and System 2 are interpreted by Daniel Kahneman, Neuro-Symbolic AI, and me.

| Perspective | System 1 | System 2 |

|---|---|---|

| Kahneman (original intent) | Fast, automatic, intuitive thinking– Based on heuristics– High-confidence responses– Trained from repetition– Works well in familiar or low-stakes situations | Slow, deliberate, effortful thinking– Requires focus and energy– Explores novel or high-stakes problems– Logical, analytical– Can override System 1 if System 1 errors or takes too long. |

| Neuro-Symbolic AI (conventional) | Neural networks– Sub-symbolic, data-driven– Fast pattern recognition (ex. images, speech)– Intuitive but opaque– Trained, not programmed | Symbolic AI– Rule-based systems (ex. Prolog, ontologies)– Logical inference, planning– Structured, interpretable– Deliberative, step-by-step |

| My Interpretation (in the context of Prolog in the LLM Era) | Knowledge Graphs– Deterministic– Human-curated or model-augmented– Represents established truths and definitions– Low-latency lookups and short-hop queries | LLMs (ex. GPT) and retrieval-based systems– Generative, probabilistic– Used for reasoning in absence of hard-coded knowledge– Handles novel questions or synthesis– Supports human creativity and exploration |

This blog isn’t about which interpretation is “correct” between System 1 and System 2. I can clearly acknowledge the relevance of all three points of view. Let me start by providing some background of the three paradigms, then explain the different shadows cast by the three points of view.

However, it really doesn’t matter why the neuro-symbolic AI folks place symbolic and neural network in the System 1 and System 2 buckets differently from me. Both parties mention it, so the points of view must be clarified.

This blog was born out of a recurring mismatch I saw between how the neuro-symbolic AI community applied Kahneman’s System 1/System 2 framing and how I’d been using Prolog in the LLM Era series. It isn’t meant as a pedantic trudge through quicksand over terminology, but rather to show that the “Prolog + LLM” workflows I described a year ago now sit comfortably under that broader neuro-symbolic umbrella—while at the same time, the reasoning for how I applied System 1/System 2 is still valid.

The Original Intent for System 1 and System 2

Kahneman’s key insight in Thinking Fast and Slow is that the vast majority of our thinking in terms of the quantity of questions/decisions are actually driven by System 1, even though we like to believe we’re rational beings using System 2.

This is mostly in the context of thinking and actions that have become “2nd Nature”. For example, when we first begin learning how to drive, we’re concentrating intensely. That intense concentration is stressful—we’re concentrating intensely, making us overly cautious, thinking through every detail of what we’re doing. That’s System 2. Over time, our driving is such that we can carry on conversations, sing along to our favorite songs, even eat while we’re driving. We won’t even remember much of the drive nor really know how long it took. Driving has been promoted to System 1.

System 1 – Fast, Intuitive, Automatic

System 1 is fast and frugal, but also prone to bias and error, because it relies on heuristics rather than logic.

- Operates quickly and effortlessly

- Feels instinctive, emotional, and “obvious”

- Handles routine tasks, pattern recognition, and gut reactions

- Can’t be turned off — it’s always on

Examples:

- Detecting anger in a voice

- Reading the word “STOP” on a sign

- Driving a familiar route

- Jumping back from a snake-shaped stick

System 2 – Slow, Deliberate, Analytical

System 2 is slower but more accurate. It’s where logic, self-control, and conscious reasoning happen — but it’s computationally intense, and often defers to System 1 unless forced.

- Requires effort and concentration

- Used when solving problems, making decisions, or analyzing unfamiliar situations

- Can override System 1 — but only when you engage it deliberately

- Gets tired with use (mental fatigue is real)

Examples:

- Calculating 27,433 × 3497 in your head

- Checking the logic of an argument with your crazy neighbor

- Deciding which route is shortest based on a map

- Filling out a complex form for the first time

Neuro-Symbolic AI

Neuro-Symbolic AI combines neural networks (subsymbolic, data-driven) with symbolic AI (rule-based, logical). It’s the attempt to unify the earlier AI symbolic attempts (expert systems of the 1980s using Prolog, Japan’s Fifth Generation of the 1980s, and the Semantic Web effort of the late 1990s through 2000s) with the “neuronal” based attempts (very early perceptron well before the 1970s, Deep Learning of the 2010s, and the current LLMs). Its roots go back a few decades, but the advancements in AI over the decades have led to unprecedented feasibility of application, thus a resurgence of this topic.

Sidenote: Intuitive meaning of subsymbolic. It’s like recognizing a friend in a crowd by their overall look and mannerisms—patterns your brain has picked up—rather than checking off a list of exact features (“tall, brown hair, green eyes”). In AI, subsymbolic means concepts live as points in a dense, multi-dimensional space (embeddings) learned from examples. The model “knows” things by how close those points sit to each other, so it smoothly handles fuzziness and nuance—but you can’t simply read off a rule or label from the numbers.

In the context of Daniel Kahneman’s System 1 and System 2 thinking, we can map these to neuro-symbolic AI as follows:

- System 1 (Neural Component): This corresponds to the neural network part of neuro-symbolic AI. System 1 is fast, intuitive, and automatic, relying on pattern recognition and learned associations. Neural networks excel at this by processing large datasets, recognizing patterns (e.g., in images or speech), and making quick, probabilistic decisions without explicit reasoning. They mimic System 1’s ability to operate on “gut” instinct, driven by training data rather than explicit rules.

- System 2 (Symbolic Component): This corresponds to the symbolic AI part. System 2 is slow, deliberate, and logical, involving conscious reasoning and rule-based processing. Symbolic AI handles explicit knowledge representation, logical inference, and structured reasoning (e.g., planning or solving math problems). It aligns with System 2’s ability to apply rules and deliberate over complex problems systematically. Symbolic AI here is reminiscent of the expert-system era tools—Prolog and Lisp of the 1980s, and even Japan’s Fifth-Generation Computing Project—where rule engines and logic programs defined the state of the art.

Neural networks in the neuro-symbolic context align with System 1 because they process information implicitly, learning from data without needing explicit rules, much like human intuition. They’re fast but can lack transparency or reasoning depth. Symbolic AI aligns with System 2 because it relies on explicit rules, logic, and structured knowledge, enabling deliberate reasoning but requiring more computational effort and predefined knowledge.

Neuro-symbolic AI aims to integrate these, leveraging neural networks for perception and pattern recognition (System 1) and symbolic systems for reasoning and abstraction (System 2), creating a hybrid that can both “sense” and “think” effectively.

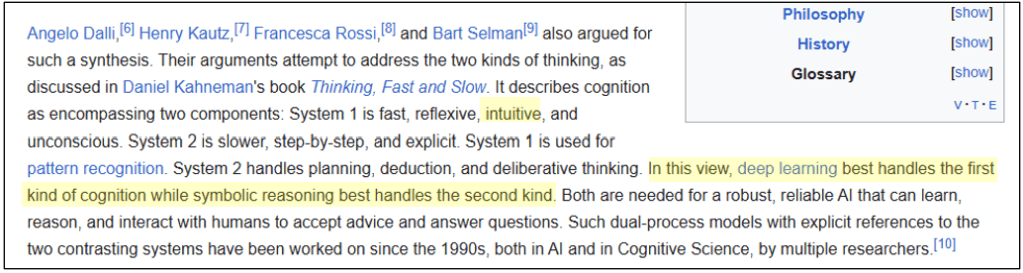

The Wikipedia page for Neuro-Symbolic AI uses the word, “intuitive” for System 1. Figure 3 is a snapshot from that page, taken on July 3, 2025.

The explanation sounds right if we’re talking about a human intelligence. We sometimes trust our gut and save a lot of time and stress. We sometimes don’t trust our gut and overthink. In either case, there’s no thinking involved. But for an artificial intelligence, I think intuitive has the wrong connotation. For an AI, the spirit of System 1 is that we execute uncomplicated rules (computationally simple), cached as knowledge, that has been developed and thoroughly vetted as valid, usually via consistent success over the course of many cases—which is how machine learning models (including neural networks) are trained.

It also validates what I say about System 1 being more neural network (“deep learning” mostly means neural networks) and System 2 sounds like those the symbolic efforts of Prolog back in the 1980s.

For an example of a neuro-symbolic AI approach in action—where pre-trained ML models are actually embedded into a knowledge graph—see my post on Embedding Machine Learning Models into Knowledge Graphs.

Neural Networks and Machine Learning

Table 2 is a comparison of a sampling of various types of neural network by a few characteristics, but most importantly, Params and Input Features.

| Model / System | Domain / Task | Architecture | Params (nn weights and biases) | Training Paradigm | Input Features (count) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AlphaGo Zero / AlphaZero | Mastering Go (Chess, Shogi) | Dual deep residual nets | 15 M – 40 M | Self-play reinforcement learning | 361 board cells (×1–8 history planes) → 361–2 888 bits |

| AlphaFold 2 | Protein structure prediction | Evoformer + Structure module | 80 M – 100 M | Supervised on PDB + MSAs | Sequence length (~50–1 000 residues) + MSA profiles (~50–1 000 columns) |

| GPT-3 / ChatGPT-3.5 | General-purpose text generation | Transformer (decoder-only) | 100 B – 200 B | Unsupervised (next-token) + RLHF | Context window: 2 048 – 16 384 tokens |

| Grok | Conversational AI (Anthropic) | Transformer (decoder-only) | ~150 B – 200 B (est.) | Unsupervised + safety fine-tuning | Context window: 2 048 – 16 384 tokens |

| U-Net (Brain-Tumor Segmentation) | MRI segmentation of gliomas | U-Net CNN | 20 M – 40 M | Supervised (voxel-wise labels) | 3D voxel grid: ~100 K – 1 M intensities |

| ResNet-50 Tumor Classifier | MRI/CT image classification | ResNet-50 CNN | 20 M – 30 M | Supervised (scan-level labels) | 2D image pixels: ~150 K values (224×224×3) |

| Credit-Card Fraud Detector (MLP) | Transaction fraud scoring | 3-layer MLP | 0.1 M – 1 M | Supervised (tabular data) | Hand-engineered features: ~10 – 100 fields |

| Cat Recognizer (ImageNet CNN) | Detecting cats in images | VGG-16 / ResNet-50 CNN | 25 M – 140 M | Supervised on ImageNet | 2D image pixels: ~150 K values |

| Sepsis Early Warning DNN | Predict onset of sepsis in ICU | 3–5 layer feed-forward DNN (ReLU) or LSTM | 1 M – 3 M | Supervised (labels from timestamped sepsis events) | 50–200 mixed features. ex. vital signs, trends, and Lab values |

| FaceNet (Face Recognition) | Verifying / identifying faces | Inception-ResNet v1 | 20 M – 25 M | Supervised (triplet-loss) | 2D image pixels: ~75 K values (160×160×3) |

The “Approx. Parameters” column measures how many individual weights and biases each neural network contains—these are the numbers the model adjusts during training to learn how to map inputs to outputs. You’ll notice LLMs like GPT-3, ChatGPT-3.5, and Grok sit in a class of their own, with hundreds of billions of parameters and a broad, generalist ability to tackle virtually any text-based task.

By contrast, systems such as AlphaGo, AlphaFold, the U-Net brain-tumor segmenter, cat detectors, and fraud-detection MLPs each have at most a few dozen million parameters and are highly specialized for one narrow domain—board games, protein folding, medical imaging, simple image classification, or tabular prediction.

And while many traditional ML models (decision trees, random forests, SVMs, etc.) are also narrow in scope, deep learning distinguishes itself by stacking many layers of these learnable coefficients so that the network can automatically discover hierarchical features end-to-end from raw data—whether it’s a specialist vision task or a giant, all-purpose language model.

Just as Kahneman’s Systems 1 and 2 both “learn” over repeated experience—our reflexive intuitions sharpen with every drive, and our deliberate reasoning deepens with every decision—machine‐learning models ingest thousands or millions of training cases until stable prediction rules emerge. You and I spent years, even decades, behind the wheel before we could seamlessly handle traffic, road conditions, and split-second hazards; an ML model can ingest equivalent examples in the timeframe of seconds to minutes.

Yet humans excel at parallel, contextual learning: we pick up driving, language, social norms, even musical skills all at once, integrating thousands of loosely defined features—weather, tone of voice, body language—into a coherent mental model. Human experience is fully immersed in all the complex glory of the real world. By contrast, an ML system learns only what you explicitly feed it: a fixed set of numeric features, a defined loss function, and no native sense of broader context. That difference—depth and breadth of representation—remains the gulf between our flexible, richly connected human intelligence and today’s still-narrow neural nets, as I address that in Thousands of Senses.

Prolog in the LLM Era

In the framework I describe in the Prolog in the LLM Era series, Prolog and knowledge graphs play the role of System 1—not because they’re “fast” in clock time, but because they deliver direct, deterministic responses based on pre-established rules and relationships. A well-curated KG lets you answer most queries with just a handful of hops through the KG or Prolog predicates, much like a reflexive answer or action: you ask “Who’s the parent of RFK Jr?” and the system immediately returns the exact fact. There’s no search over open-ended possibilities—just a lookup in a structured, human-defined network of truths.

By contrast, LLMs embody System 2 in this mapping. When a KG and/or Prolog program can’t handle a question—because it’s novel, ambiguous, or requires synthesis of scattered bits of knowledge—you defer to the broadly-scoped LLM. Here, “thinking” truly means exploring nests of possibilities, generating hypotheses, and iteratively refining an answer. An LLM doesn’t have rigid rules; it composes text by traversing a probabilistic landscape trained on billions of tokens, which resembles System 2’s methodical evaluation of alternatives before committing to a move.

A good example is when I see the word “pizza”. I don’t think I process that in a System 2 manner: “P … I … Z … Z …. A … ah, pizza”. I’ve seen that word so many times and eaten so many pizzas, that the word, “pizza” is a singular symbol, a System 1 recognition. (It’s 4th of July as I write this and we’re having pizza!)

To summarize my framework:

- System 1: Prolog/knowledge-graph lookups (deterministic, rule-based “reflexes”).

- System 2: Broad-scope LLMs (probabilistic, generative exploration of possibilities, hypothesis generation, and iterative refinement when rules alone won’t suffice).

This interpretation diverges from two other perspectives:

- Kahneman’s original:

- System 1 is fast, intuitive, and often unconscious; System 2 is slow, effortful, and deliberate.

- Speed and cognitive load are the differentiators.

- Conventional neuro-symbolic AI:

- System 1 = neural networks (CNNs, Transformers) for perception and pattern matching

- System 2 = symbolic engines (Prolog, ontologies) for logic and planning

In the context of Enterprise BI, in which I usually operate, speed is secondary to trust and traceability (well, depending on the customer). Prolog/KGs guarantee that any inference is traceable and explainable—it’s code. LLMs, by contrast, must be guided, questioned, and constrained (for example, via RAG) to increase the probability that their creative proposals remain valid. This separation lets us lean on our “System 1” substrate for everyday queries and invoke “System 2” only when innovation—and the inevitable mitigation of hallucinations—is required.

The Symbiotic Relationship Between Knowledge Graphs and LLMs

The symbiotic relationship between knowledge graphs and LLMs has been a growingly popular topic over the past few years. Basically:

- Knowledge Graphs have traditionally been manually crafted by teams of subject-matter experts and ontologists/taxonomists.

- The problem with KGs is that they are a real pain to create. I’ve talked about my experience with this back in 2004 attempting a knowledge graph of the internals of SQL Server. It’s a mess to create manually, and even harder to maintain as the world changes from under its feet.

- LLMs have effectively consumed knowledge across an incredibly wide and deep breadth of humanity’s writings. In a sense, the large LLMs of today (GPT, Grok, etc.) are actually knowledge graphs! Well … at least as far as the training material available to them. LLMs may not look like knowledge graphs, but within all that vector encoding is the know-how.

- The problem with LLMs is that they hallucinate.

- KGs and LLMs can mitigate each other’s problems.

- LLMs can mitigate the problem of developing and maintaining KGs by setting up first drafts of many parts of KG. LLMs can even help validate KGs—after all, even human SMEs can make mistakes.

- KGs can reality-check the output of LLMs.

The same could be said of encoding rules in Prolog instead of (or in addition to) KGs, as I described in Knowledge Graphs vs. Prolog. The arrival of these powerful LLMs, even with their limitations, has blown open the door to the promise of expert systems going way back to the 1980s.

This symbiotic relationship is really the meta-structure of the end-product of my book Enterprise Intelligence—the Enterprise Knowledge Graph (EKG). The EKG is composed of four sub-structures as shown in Figure 4:

- Knowledge Graph (KG): A comprehensive ontology/taxonomy knowledge graph built to W3C semantic web standards.

- Insight Space Graph (ISG): Insights automatically derived from the natural activity of the enterprise-wide population business intelligence consumers.

- Tuple Correlation Web (TCW): Bayesian-inspired web of correlations between subject and object tuples also automatically derived from the natural activity of the enterprise-wide population business intelligence consumers.

- Data Catalog: The three parts above are intricately wired together through enterprise-wide database metadata.

The comprehensive EKG serves as a deterministic “knowledge base”—built from objectively traceable inputs (BI-derived ISG and TCW elements plus SME-curated KG facts). It acts as a solid, rule-bound “consultant” that can be queried by a private, wide-scope, highly versatile, intuitive LLM—whose generative insights are inherently stochastic rather than strictly rule-driven.

The EKG grounds the LLM is reality with it’s fully traceable data, while the LLM assists with a tremendous share of tedious work contributing towards the maintenance of the EKG—assisting SMEs with building and maintaining the KG and assisting data engineers with all manner of IT infrastructure.

What’s Changed Since “Prolog in the LLM Era – Part 1” (August 4, 2024)

When I first posted Part 1 on August 4, 2024 (about a year ago at the time of writing), “better models” in the LLM world meant “bigger neural nets”—models with more parameters, more compute. Today, “model” has grown to encompass entire query pipelines built around LLMs, where a user prompt spawns a multi-component process cycle. While most of the items in this list were born before August 2024, they were still “cutting-edge” for the most part but have grown into being relatively mainstream (pretty much a given) over the past year:

- RAG (Retrieval-Augmented Generation) steps that fetch documents, graph fragments, or database rows. RAG first breaks down a prompt into steps, then methodically executes them. A good, if not perfect, analogy is that RAG is to LLMs as FOR-EACH is to programming languages.

- Multi-step reasoning via Chain-of-Thought, where the model “thinks out loud” by breaking a problem into intermediate sub-prompts and weaving the answers together.

- Multi-step reasoning via multi-agent orchestration, calling out to specialized LLMs, knowledge graphs, or other services—and then integrating their outputs into a final result.

- Fine-tuning and adapters—specializing LLMs on domain data or via PEFT methods (LoRA, prefix-tuning).

- Model compression (“Deep Compression”)—pruning, quantization, and distillation to shrink huge nets into nimble, production-ready engines.

- Mixture of Experts (MoE)—a dynamic model architecture where different components (or “experts”) act like specialized agents, selectively activated depending on the query. This allows for scalable and efficient handling of diverse tasks by routing sub-problems to the most relevant expert agent, improving both performance and specialization without running the entire model at full capacity.

- Retrieval-Augmented Reasoning (RAR): An emerging concept in AI, blending retrieval-based methods with reasoning capabilities. It’s a hybrid approach that leverages the strengths of both neural networks and structured knowledge to improve the accuracy and contextual relevance of LLMs. LLM pipelines first fetch relevant documents, KG fragments, or database rows (via embeddings or semantic search), then invoke symbolic engines over that retrieved context—combining the breadth of neural nets with the precision of curated facts.

In other words, what you see as a single “answer” to a prompt (no matter how creatively prompt-engineered) to an LLM is now often the product of many moving parts.

This is an important point towards how LLMs are System 2. Although they are at their foundation, neural networks, they’ve always been embedded in some process. But that list of processes above moves LLMs a long way down the path from hallucinations. Yes, ChatGPT o4-mini and other advanced LLMs (which are embedded in some sort of process) still hallucinate. But I think that’s because we’re expecting more and more from them as we deploy AI into more use cases. The more complicated or complex the question, the greater the level of inaccuracy or downright hallucination.

In fact, the symbiotic relationship we just discussed is a kind of RAG, a process that asks an LLM, but attempts to corroborate with a KG for fact-checking or simply supplying answers to direct sub-questions.

Looser Definitions and an Expanded Landscape for Neuro-Symbolic AI

Since those earlier days of neuro-symbolic AI when:

- “neural” primarily meant “convolutional nets”,

- “symbolic” meant Prolog, Rules Engines, or knowledge graphs,

- the technologies picked up new capabilities blurring the lines,

the boundaries have softened and grown more inclusive on System 1 and System 2 fronts:

- System 1’s Neural Side Has Become “All the Machine Learning Models”

What counts as a “neural” or subsymbolic component now spans everything from deep Transformers to classical ML models trained for a single task—support-vector machines, decision trees, random forests, even clustering algorithms. Any model that learns from data rather than being hand-coded can play the System 1 role:- Targeted task experts. A fraud-detection Random Forest, a predictive-maintenance XGBoost model, or a CNN tuned for medical imaging can all act as fast, learned pattern recognizers.

- Feature extractors. Embedding models that turn text, images, or graph neighborhoods into vectors are now often the first “instinct” a larger pipeline calls upon.

- System 2’s Symbolic Side The symbolic repertoire has likewise blossomed beyond pure logic programming:

- Knowledge graphs combining ontology-driven schemas with curated facts.

- Business-rules engines (Drools, OpenL Tablets) that apply if-then chains over event streams or transaction records.

- Constraint solvers and planners (e.g., Z3, OptaPlanner) for scheduling, resource allocation, or verification tasks.

- Microservices that encapsulate discrete decision logic—take input parameters, execute a small “rule set,” and return a deterministic result. In effect, each microservice endpoint becomes a little symbolic oracle your LLM “System 2” can call when it needs a reliable sub-answer.

Together, these expansions mean that a neuro-symbolic pipeline might look less like “neural networks + rules engine” and more of a complex, iterative, multi-faceted orchestration:

- Data preprocessor (ex. a microservice that normalizes, validates, or enriches raw inputs).

- Feature-embedding model (a small Transformer or even a lightweight word-embedding service).

- Vector search service to retrieve similar cases or facts from a KG.

- Rule engine to apply business-domain constraints (eligibility checks, compliance filters).

- LLM orchestrator to decompose the user query, call the above sub-services in parallel, then recombine their outputs into a fluent answer.

In this view, System 1 is a constellation of learned “instincts”—not just big neural nets but any data-driven predictor—and System 2 is the glue and logic layer—not just Prolog, but every deterministic, interpretable, and parameter-driven service you can bolt on. This richer ecosystem lets us mix and match the fastest, most reliable reflexes with the most creative, open-ended reasoning, invoking exactly the right tool for each subtask while maintaining trust, explainability, and the ability to innovate.

The current interpretation of RAG is, in fact, very similar to the process of invoking a neuro-symbolic AI system. Both begin with a natural-language prompt and proceed by breaking it down into smaller sub-questions or tasks. Both retrieve structured or semi-structured data—from vector databases, SQL engines, or knowledge graphs—and both attempt to orchestrate a reliable answer by weaving together facts, logic, and pattern recognition.

The key differentiating factor is that RAG, as originally conceived, was a retrieval pipeline that could include symbolic reasoning—but didn’t have to. Today, however, as RAG systems increasingly call out to microservices, constraint solvers, logic engines, and curated knowledge graphs, the line between RAG and neuro-symbolic AI has largely disappeared. What once felt like a research distinction is now just a spectrum of practical architecture choices. In that sense, a well-architected RAG system is already a neuro-symbolic system—it just might not realize it yet.

LLMs as Wide-Scope System 2

A year ago (Aug 2024), LLMs were in the middle of transitioning from just a big transformer architecture neural network trained on massive volumes of text to multi-modal, generalist engines that can digest code, tables, graphs, and web results—and collaborate with AI Agents (including domain-specialized fine-tuned LLMs) and tools to fill gaps.

Because of this process-oriented nature of the latest “AI models”, I continue to treat LLMs as System 2 in my framework:

- LLMs are still neural networks but extremely broad rather than narrowly task-focused (as are most machine-learning models).

- They can answer many questions directly and very quickly.

- To improve accuracy, modern LLM pipelines leverage System 1 (Prolog and KGs) as sub-routines:

- The LLM breaks your question into sub-questions.

- Those sub-questions are answered by Prolog predicates or SPARQL queries against the KG.

- The LLM then synthesizes those precise, deterministic results into a final, coherent narrative.

This orchestration mirrors how our own brains defer to quick instincts when possible but fall back on deeper reasoning when the situation demands it.

System 1 Still Carries the Load in Terms of Query Quantity

It’s true that some KG or Prolog queries can be expensive or slow in practice—complex SPARQL joins, deep proof searches, or heavyweight inference. But that only underscores the principle: most of the time, System 1 handles the routine, even if it sometimes takes a few hundred milliseconds or a full second. And when System 1 can’t immediately resolve a question, it may emit a quick heuristic or placeholder and let System 2 (the LLM) take the lead.

The vast bulk of our thinking (and of real-world query traffic) remains in System 1—but the inevitable exceptions of a System 1 query (ex. can’t find an answer or taking too long) trigger System 2’s richer, multi-step reasoning. And since mid-2024, System 2 in AI has become both more powerful and more complex, blending neural nets, retrieval processes, and symbolic constraints into a single, coherent orchestration.

Conclusion: Analogies are Made to be Broken

In the end, the argument over precisely how the neuro-symbolic AI community maps neural versus symbolic components—and how “Prolog in the LLM Era” designates LLMs as the neural (System 1) side and Prolog + knowledge graphs as the symbolic (System 2) side—is largely moot, because the field has dramatically (and seemingly organically) broadened what counts as “neuro-symbolic AI”.

No longer confined to a neural network paired with symbolic data of some sort, today’s neuro-symbolic AI umbrella encompasses everything from fine-tuned ML classifiers and embedding models to graph neural networks, sequence models, Prolog engines, OWL reasoners, and even microservice-based rule chains.

Here are a few representative references that back up my claim that the umbrella and definition of neuro-symbolic is evolving to the point it encompasses Prolog in the LLM Era:

- Garcez & Lamb (2020) introduced the idea of a “third wave” of neuro-symbolic AI, arguing for principled integrations of deep learning with rich symbolic knowledge—well before LLMs captured the spotlight arxiv.org.

- Hitzler & Sarker (2022) surveyed the state of the art and noted that modern neuro-symbolic systems routinely combine graph embeddings, formal ontologies, and end-to-end differentiable modules, rather than limiting themselves to rigid “neural+logic” pairs en.wikipedia.org.

- Gibaut et al. (2023) classified nearly two hundred neuro-symbolic approaches and highlighted that many pipelines glue together Transformers, GNNs, Prolog predicates, and business-rules engines—underscoring that “neural” now means any ML model and “symbolic” any structured reasoning component arxiv.org.

- De Long et al. (2023) surveyed reasoning over knowledge graphs with neural methods and observed that “neuro-symbolic” spans both tight, layer-wise grounding of logic in networks and loose orchestration of black-box LLMs with external rule systems arxiv.org.

From the “Prolog in the LLM Era” perspective, the neuro side are LLMs embedded within a process such as RAG, while the symbolic side is a combination of knowledge graphs (semantic web) and Prolog. But more abstractly, it mirrors two complementary cognitive modes.

The neuro side is like our semi-supervised, self-organizing brain that forms patterns from the countless events of a rough and tumble lifetime in a complex world—captured in the wide and deep variety of humanity’s writings and therefore inherently vulnerable to misinterpretation. On the other hand, the symbolic side encodes the explicit truths and rules we’ve agreed upon. Therefore, LLM-powered pipelines offer an intuition-driven, experience-based understanding akin to human subconscious pattern matching, whereas the symbolic layer provides the structured, verifiable framework that grounds and constrains those insights.

When we use Kahneman’s System 1 and System 2 insight as analogies in the neuro-symbolic AI world and Prolog in the LLM Era series, the analogy is very effective at providing intuition individually. But when we apply that analogy to the two paradigms, the analogy breaks down. That’s OK. Analogies are made to be broken. As I mention in Analogy and Curiosity-Driven Original Thinking, analogies are meant to be seeds of creativity. They aren’t a cut/paste solution.

So Prolog in the LLM Era now fits into the neuro-symbolic umbrella. But both are sculpted to the point where the analogy of System 1 and System 2 must stretch too much. That’s OK. An analogy is just seed, an inspiring pattern—it’s not a definition. It’s the same path, but a different journey.

Table 3 is a listing of some of the major paradigms that can play into neuro or symbolic sides. By the “Creative, Metaphorical” column, I mean in the vein of what I wrote in Analogy and Curiosity-Driven Original Thinking.

| Paradigm | Fast When… | Slow When… | Deterministic | Creative, Metaphorical |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional ML (trees, SVM, etc.) | Feature vector lookup → one pass through model | Complex ensembles or hyperparameter search | Yes (fixed rules) | Limited—a fixed set of hand-engineered features |

| CNNs (vision) | Single forward pass over image (O(pixels·layers)) | Large image pyramids, multi-scale sliding windows | Yes (no randomness at inference) | Moderate—learned hierarchies of visual features |

| RNNs / Transformers (sequence) | One pass over tokens (O(tokens·layers·heads)) | Very long contexts (quadratic attention) | Yes (unless dropout used) | High—sequence synthesis, translation, summarization |

| GNNs (graphs) | Fixed-depth neighborhood aggregation (O(nodes+edges)) | Many message-passing iterations or deep stacks | Yes (graph isomorphism limited) | High—learned relational embeddings |

| Prolog / Logic and Rules Engines | Few-hop rule lookup (bounded depth) | Deep backtracking or large search trees | Yes (pure logic) | Low—only as deep as the rule base allows |

| Knowledge Graph / Semantic Web | SPARQL with short property paths (O(hops)) | Complex joins, inference via OWL reasoners, or non-trivial SWRL queries. | Yes (queryable graph) | Moderate—ontologies + reasoning rules |

| LLMs alone (GPT, etc.), at most prompt engineering | Single forward pass decoding (O(tokens·layers)) | Long-context chaining, iterative prompting | No (sampling randomness) | Very high—emergent grammar, analogies, synthesis |

| LLM Pipelines (RAG, CoT, agents) | One round of retrieval + one decode | Multi-round retrieval, multi-agent orchestration | Mixed (some deterministic subcalls) | Maximal—tool use, hybrid reasoning, dynamic planning |

All the items listed in Table 3 are capable of returning an answer to a simple question very quickly, while some can address complicated or even complex questions with levels of potential hallucinations commensurate with the level of complication/complexity.

In our lives, the vast majority of actions our brain decides upon is “2nd nature”, automatic. It’s massively numerous and reliable (high precision)—that’s “Plan A” (System 1). But we naturally apply “Plan B” (System 2) when we run into an exception—iterative and recursive. That includes any unexpected result, the answer to a question is taking too long, or we’re in a critical situation requiring instant response. In a pinch, our amygdala automatically finds a quick and dirty action (run!) to buy a few seconds for our System 2 brain to analyze further. The problem with Plan B is that we just made it up, so we don’t have a history of success/failure, and maybe not sufficient time to adequately test it.