Contents

- What’s the difference between a tuple and a vector? Can a tuple ever be a vector?

- What is pre-aggregation in OLAP?

- What are “Insights” (in the context of Enterprise Intelligence)?

- What are the Three Time-Based Relationships of Time Molecules?

- Support Vector Machine Build Cost

- LLM–Knowledge Graph Symbiosis

- Baby Step for Incorporating the Semantic Web into BI

- Tips for Auto-Seeding a new EKG

- Why bother with BI in this era of LLM-driven AI, Spark, and cloud data warehouses?

- How is the TCW System ⅈ probing optimized?

- How can you be a Good wikidata.org Citizen?

- Is there a List of Interesting videos and articles that support the concepts in Enterprise Intelligence?

- What Do You Mean by “Knowledge is Cache”?

- What is the importance of SQL GROUP BY statements?

- Should we use a private LLM?

What’s the difference between a tuple and a vector? Can a tuple ever be a vector?

All vectors are tuples, but only purely numeric tuples (with vector-space operations) are vectors.

- A tuple is simply an ordered list of elements, which can be of any type (numbers, strings, dates, labels, etc.).

- Example:

("Bikes", 2025, 5000)is a 3-tuple, but you can’t add or scale it because “Bikes” and “2025” here are non-numeric labels.

- Example:

- A vector is an ordered list of numeric values (elements from a field) equipped with well-defined addition and scalar-multiplication operations that satisfy the vector-space axioms.

- Example:

(5000, 3000, 12.5)is a 3-vector in ℝ³—you can add two such vectors, multiply by scalars, compute dot-products, and measure distances.

- Example:

- Overlap: Every numeric vector is also a tuple (an ordered list), but not every tuple is a vector. A tuple only becomes a vector when:

- All components are numeric, and

- You define how to add two tuples and multiply them by scalars (the standard component-wise operations).

What is pre-aggregation in OLAP?

Pre-aggregation means computing and storing summaries (e.g. sums, counts, averages) of your detailed fact data ahead of time—across various combinations of dimensions—so that analytic queries can read those summaries instantly instead of scanning millions (or billions) of raw rows at query time. See The Ghost of OLAP Aggregations – Part 1.

Why use pre-aggregation?

- Performance: Drastically speeds up complex queries (e.g., month-to-date sales by product and region) by hitting small summary tables instead of the full fact table.

- Scalability: Supports interactive slicing, dicing, drilling, and pivoting over large datasets without taxing your database.

- Concurrency: By serving queries from small aggregate tables, the system avoids heavy compute on the base fact, allowing many users to query simultaneously without contention.

- Predictability: Provides consistent query response times—even as data volumes grow.

How do OLAP engines (SSAS, Kyvos) implement pre-aggregation?

- SQL Server Analysis Services (SSAS):

- Uses Aggregation Designs to pick dimension hierarchies and measure groups.

- Builds multi-level aggregate tables inside the cube (stored in MOLAP or ROLAP storage).

- Supports usage-based optimization—profiles query patterns, then dynamically refines which aggregates to build.

- Offers incremental process so only changed partitions rebuild aggregates.

- Kyvos Analytics:

- Creates distributed cubelets on Hadoop or cloud storage, each holding pre-aggregated slices.

- Leverages a massively parallel engine to shard aggregates across nodes.

- Uses dynamic aggregate pruning to only read relevant cubelets per query.

- Integrates with modern data lakes for on-demand aggregate re-calculation without full cube reloads.

What’s the trade-off?

- Storage Cost: More disk space for summary tables or materialized views.

- Load Time: ETL must compute and refresh aggregates (batch or incremental), adding complexity.

- Flexibility: Ultra-detailed ad-hoc queries outside pre-defined aggregations may still hit the raw data or require on-the-fly aggregation.

Pre-Aggregation vs. On-The-Fly Aggregation

| Aspect | Pre-Aggregation | On-The-Fly Aggregation |

|---|---|---|

| Query Speed | Instant (reads precomputed data) | Slower (scans raw data) |

| ETL Complexity | Higher (build & maintain summaries) | Lower (no extra ETL) |

| Storage Footprint | Larger (additional summary tables) | Minimal (only raw fact tables) |

| Flexibility | Limited to defined cubes/views | Fully flexible but slower |

When should I use pre-aggregations?

- High-volume analytics where sub-second response is critical.

- Repeatable reporting patterns (e.g. monthly, quarterly dashboards).

- Interactive BI tools that expect instant pivots and drill-downs.

Example

1. Base fact table (billions of rows)

Schema: FactSales(OrderDate, Product, Region, Sales)

| OrderDate | Product | Region | Sales |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2025-01-01 | Bikes | North America | 120 |

| 2025-01-01 | Cars | Europe | 340 |

| … | … | … | … |

| 2025-12-31 | Bikes | Asia | 215 |

| 2025-12-31 | Cars | North America | 480 |

That single table might hold 5 billion rows—too large for sub-second ad-hoc queries.

2. Pre‐aggregation designs

Below are a few of the aggregate combinations we build ahead of time:

| Agg Name | Dimensions | Measures | Grain |

|---|---|---|---|

| Year_Product | Year | SUM(Sales) | (2025, Bikes) |

| × Product | COUNT(*) | (2025, Cars) | |

| Year_Region | Year | SUM(Sales) | (2025, North America) |

| × Region | (2025, Europe) | ||

| Product_Region | Product × Region | SUM(Sales) | (Bikes, Asia) |

| (Cars, Europe) |

3. Query flow

- Lookup pre-agg: When you ask

SELECT SUM(Sales) FROM FactSales WHERE YEAR(OrderDate)=2025 AND Product='Bikes', the engine checks the Year_Product aggregation first. - Hit → returns the pre-computed SUM in milliseconds.

- Miss → if you queried a combination not covered (e.g. Year+Region+Product), it either:

- Falls back to on-the-fly aggregation over FactSales (slower), or

- Remaps to a closest pre-agg plus a small roll-up if supported.

4. Why it works

With a well-designed set of pre-aggregations that match 80–90% of your common query patterns, the OLAP engine “hits” the right aggregate table most of the time—delivering interactive performance on billion-row datasets.

What are “Insights” (in the context of Enterprise Intelligence)?

Insights refer to the salient patterns, anomalies, relationships, and metrics observed by business users while exploring visualizations generated from BI query results. These visualizations—such as bar charts, line graphs, scatter plots, and heatmaps—serve as the lens through which human users detect meaningful observations.

Insights include, but are not limited to:

- Inflection points (where growth or decline changes pace)

- Trends and seasonality

- Outliers and anomalies

- Inequality metrics such as the Gini coefficient

- Correlations or clusters

- Unexpected gaps or spikes

Some insights may be obvious to one user but missed entirely by another—a phenomenon akin to a “Where’s Waldo” effect. Others may not seem relevant to the current viewer but may prove valuable when surfaced to different stakeholders or intelligent agents (AI).

In an Enterprise Intelligence framework, insights are not just ephemeral “aha” moments. Instead, they are captured, stored, and made discoverable—creating a shared memory of intelligence that can be reused, validated, or built upon by others across the organization. This collective intelligence can support:

- Better decision-making across teams

- Cross-domain collaboration

- AI-driven automation and recommendations

Ultimately, insights are the reason BI analysts use visualization tools in the first place. They represent the bridge between data and action—the distilled value from the mountain of raw metrics that flow through the BI system.

What are the Three Time-Based Relationships of Time Molecules?

Time is the ubiquitous dimension. Without it, nothing happens—there are just things, not processes. So in the world that is constantly changing, undermining what we’re learned, we rebuild our understanding by observation. These are three ways that we observe what’s going on.

- Markov Models – “What happens next?”

At the process level, we look at sequences of events across many instances (cases) of a process.- Question: Given the last event, what is the next event?

- Example: In a customer support process, after “Ticket Assigned,” the next event might be “Ticket Resolved” 65% of the time, “Customer Follow-up” 25%, and “Escalated” 10%.

- This captures transition probabilities between events of a process.

- Conditional Probabilities – “Under these conditions, how likely is it?”

We focus on context: given certain conditions or accompanying events, what is the probability a particular event will occur?- Question: Given a set of circumstances, how likely is a given event?

- Example: “Given that the customer is VIP and the ticket priority is High, the probability of escalation is 45%.”

- This reflects the idea of what fires together, wires together — associations strengthened by repeated co-occurrence.

- Correlations – “Do these things move together over time?”

Here, we measure how two variables or event measures rise and fall together over increments of time.- Question: How closely do two different metrics track each other over time?

- Example: Weekly call volume and average customer wait time might have a correlation of 0.82, suggesting a strong positive relationship.

- This doesn’t prove causation but can point to potentially related behaviors or metrics.

How they connect

Markov Models (1) and Conditional Probabilities (2) together form the two halves of a Hidden Markov Model (HMM) — the transitions between states (Markov) and the probabilities of observed events given those states (Conditional).

Correlation (3) operates alongside them as a discovery mechanism, hinting at relationships worth testing or modeling. See Correlation is a Hint Towards Causation.

Support Vector Machine Build Cost

An SVM gives us a quantitative border to measure “how far we can push,” but it’s heavier than the usual linear/stat functions (SUM/AVG, inflection points, Markov models). Two practical points:

- Training vs serving.

A linear SVM is light to train and very cheap to serve (just a dot product per row). A kernel SVM (e.g., RBF, curved borders) can be slow to train and costlier to serve because it depends on many support vectors. OLAP cubes help by delivering the training slice fast, but model fitting is still the expensive step. - Build on demand, then re-use.

When a boundary question is new (features/slice not seen before), the agent can approve a build. We submit it to a background pipeline, cache the model as an Insight Space Graph model (tied to the QueryDef, feature list, scaler, and data slice), and serve it immediately on future queries. That turns a one-time heavy compute into a reusable asset.

Implementation rules of thumb:

- Default to linear SVM for most BI use cases—fast to fit, tiny artifact (store just weights/bias), exact margins for “allowable Δ.”

- If curvature is clearly needed, allow kernel SVM or a kernel approximation so serving stays near-linear.

- Prefer margins over calibrated probabilities in real time; probability calibration can run in the background.

- Version and expire models based on data freshness (batch/window), so cached borders track the underlying cube.

The first time may take longer, but after that the SVM becomes part of the ISG, ready to answer “how far can I push?” or “what’s the minimal change to reach state 8?” with near-instant latency.

LM–Knowledge Graph Symbiosis

A symbiotic relationship between Large Language Models (LLMs) and Knowledge Graphs (KGs) arises when each compensates for the other’s weaknesses while amplifying the other’s strengths.

- LLMs excel at fluid reasoning and contextual synthesis. They can interpret natural language, infer intent, and generalize from incomplete information. However, their knowledge is implicit, approximate, and decoupled from provenance—they recall patterns but cannot guarantee truth.

- Knowledge Graphs, on the other hand, hold explicit, structured truth. They define entities, relationships, and ontologies that are verifiable and contextualized, but are static and brittle without external interpretation.

In combination, the LLM becomes the context engine—the conversational and interpretive front end—while the Knowledge Graph becomes the semantic ground truth that anchors responses and decisions. The LLM retrieves and composes meaning from the KG, and the KG in turn gains new inferred links, entity definitions, and natural-language descriptions from the LLM’s interpretive feedback.

This is a bi-directional learning loop:

- The LLM queries the KG to constrain its imagination with reality.

- The KG absorbs insights from the LLM to expand its ontology with newly discovered or reformulated relationships.

In practical terms, this symbiosis mirrors the human balance between intuition and memory. The LLM acts like the right hemisphere—pattern-oriented, associative, creative—while the Knowledge Graph acts like the left hemisphere—structured, logical, and archival. The result is not merely retrieval-augmented generation (RAG), but a continuously evolving hybrid intelligence capable of both contextual understanding and logical consistency.

See “Symbiotic Relationship between KGs and LLMs”, page 94 in Enterprise Intelligence.

Baby Step for Incorporating the Semantic Web into BI

If you’re new to knowledge graphs and the Semantic Web, I wrote a page on a baby step towards incorporating the Semantic Web into your BI platform. It was intended to be an appendix in Enterprise Intelligence, but missed the cut. This baby step will take you from:

- Acquainting yourself with knowledge graphs through playing with Wikidata.org and playing with SPARQL using Wikidata’s query tool.

- Introduction to Semantic Web terms—SPARQL, RDF, OWL, IRI …

- Selecting a platform – I recommend Jena Fuseki as the open source graph database, Stanford’s Protege as a visualization tool.

- Retrofitting your BI database for the Semantic Web.

- An MVP for BI visualizations—as discussed in Enterprise Intelligence, Contextual Information Delivery, page 284. Figure 1 shows the associated snapshot from the book, Figure 100 on page 285.

Next baby step: Tips for Auto-Seeding a new EKG

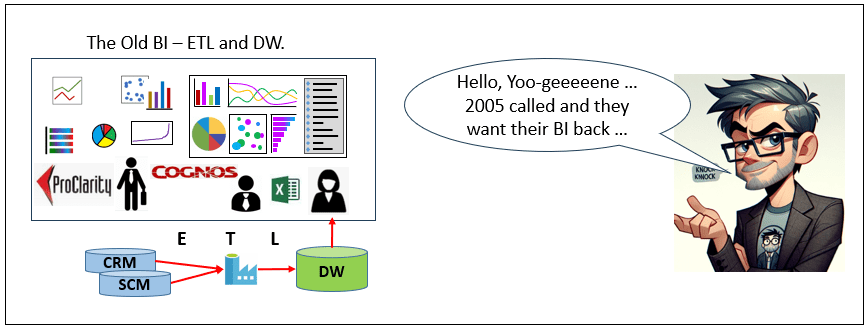

Why bother with BI in this era of LLM-driven AI, Spark, and cloud data warehouses?

In today’s AI discourse, Business Intelligence can feel like legacy infrastructure—associated with slow cubes, brittle ETL, and static warehouses. But that framing overlooks what BI actually represents architecturally: the enterprise’s most curated, trusted, and decision-ready data substrate. BI integrates domain data, harmonizes terminology into a shared business language, enforces governance, and presents information in interpretable dimensional models designed for human and machine consumption alike.

Modern AI systems actually amplify the need for the curation of BI. LLMs, agents, and machine learning pipelines are only as reliable as the data they reason over. Without curated semantic layers and governed data products, AI operates on fragmented, inconsistent signals. Contemporary patterns such as Data Mesh, Data Vault, and cloud-scale warehousing have already evolved BI beyond its monolithic past, while AI now helps stitch distributed domains back into coherent knowledge systems rather than replacing them.

BI is the art and science of transforming raw data to a humanly intuitive level of abstraction.

There is also a cognitive analogy. Human intelligence does not reason directly over raw photons, sine waves, or molecular signals. Early sensory processing (such as visual cortex transformations) converts raw input into higher-order constructs the brain can interpret and reason about. BI plays a similar role for the enterprise—transforming operational exhaust into structured, decision-grade information. For this reason, even in an AI-driven architecture, BI remains the spearhead of enterprise intelligence: not antiquated infrastructure, but the curated substrate upon which reliable machine reasoning depends. See Thousands of Senses.

What is the importance of SQL GROUP BY statements?

A GROUP BY is a foundational SQL construct used to aggregate detailed data into summarized form. It partitions rows in a fact table into groups based on one or more shared dimension values, then computes metrics (aggregations) for each group.

In Business Intelligence and OLAP query patterns, GROUP BY statements are among the most common query forms because they transform raw transactional data into analytically meaningful structures suitable for reporting, visualization, and correlation analysis. It’s the query pattern that addresses the fundamental slice and dice query.

Example:

SELECT Customer, SUM(Sales) AS TotalSalesFROM FactSalesGROUP BY Customer;This query summarizes total sales per customer.

Parts of a GROUP BY query

- SELECT (dimension columns): The categorical fields that define how data is partitioned (e.g., Customer, Product, Region).

- SELECT (aggregation functions): Metrics computed for each group (e.g., SUM, COUNT, AVG, MIN, MAX, STDEV).

- FROM (source table or fact table): The dataset being summarized, typically a transactional or event-level table.

- GROUP BY clause: The instruction that partitions rows into groups sharing identical dimension values.

- Optional filters (WHERE / HAVING): WHERE filters rows before grouping; HAVING filters groups after aggregation.

Result structure

The output of a GROUP BY query is a summarized tabular dataset (dataframe):

- Each row represents one unique combination of the grouped dimensions.

- Each row therefore constitutes a tuple—a context-bound data record defined by its dimensional coordinates and associated aggregated metrics.

Why it matters in OLAP patterns

GROUP BY queries:

- Produce dimensional summaries used in dashboards and reports

- Form the basis of cubes and semantic models

- Generate tuples that can feed correlation, trend, and process analyses

In analytic architectures, GROUP BY is the primary mechanism for transforming granular events into structured insight artifacts.