Previously on Embedding a Data Vault in a Data Mesh …

In Part 1, I introduced the notion of using a Data Vault as a domain-spanning “data warehouse layer” in a Data Mesh.

- Part 1 – Introduction. Overview of the main idea of implementing a Data Vault in a Data Mesh. I also briefly discuss the main components of Domain Models, Data Vault, and Data Mesh.

- Part 2 – Event Storming to Domain Model – Decomposition of an enterprise into a set of types (entities, things) and functions (the things the that happen between the entities). These are the pieces of the 1000-piece jigsaw puzzle from which a domain model is assembled. In turn the set of OLTP-side microservices are derived from the domain model.

- Part 3 – Domain Model to Data Vault. The domain model, done properly, should naturally translate well into the hubs, satellites and links of the OLAP-side Data Vault. ETA: 3/07/2022

- Part 4 – ETA: 3/21/2022

- a – Data Vault to Data Marts (Business Vault) – This is the point where the representation of data that still bears resemblance to the OLTP side transforms to the OLAP side as star-schema-based data marts.

- b – Data Marts to OLAP Cubes – The Data Marts are presented to the consumers in a manner as optimized and user-friendly as possible.

- Part 5 – Data Product Composition – This is the can that keeps getting kicked down the road. Sound integration of data across diverse data sources is a very painful process. That is what I consider “hard problem” of Business Intelligence. ETA: 3/28/222

As I mentioned in Part 1, this blog series is easier to follow if you have a basic understanding of Data Mesh and Data Vault. Domain Driven Design (DDD) helps as well.

If you’ve read my prior blog, Data Vault Methodology Paired with Domain-Driven Design, this Part 2 may look and sound familiar. In this part, you’ll run an Event Storming that yields a bounded-context map and a first-pass Domain Model—ready to translate into Data Vault hubs, links, and satellites in Part 3.

Your Situation

Before continuing, I need to be clear that the intent to build a DDD-architected, microservices environment is not a requirement for the purposes of this blog series. Event Storming is a popular early process in the effort to rearchitect a monolithic architecture into a set of loosely-coupled coherent components – bounded contexts and domains.

If your current environment is already microservices architected through domain-driven design, you could skip this blog over to Part 3 – Domain Model to Data Vault. In that case, that microservices environment has already decomposed the enterprise into its functional components. This would be the ideal situation for a data vault and/or a data mesh.

However, even if a green-field, blue-sky microservices re-architecture isn’t in the works, I would advise reading through since:

- There probably will be disconnects between how I describe DDD here and how it was implemented in your environment. This is unavoidable since every environment is different and something of an enterprise scope is bound to require adjustments.

- Your environment may be only partially converted to microservices. So some domains would still need to go through this effort.

- Even if there are no plans to do go through a DDD microservices effort on the OLTP systems, the Data Vault can present a virtual microservices layer. That virtual untangling is of much value even if the OLTP systems are not actually microservices.

The Sample Use Case – Gowganda Hospitality

Gowganda Hospitality is a fictional corporation. It’s one of thousands of conglomerates of mixed franchise brands. In this case, a mix of hotels and restaurants. The number of franchise stores range from one to hundreds.

Figure 1 depicts a partial map of Gowganda Hospitality’s locations before merging with another conglomerate, Shinarump Corp. The varied shapes of each location illustrates the intuitive need to conform each into optimized, tried and true processes.

Note: Gowganda and Puddingstone are very cool conglomerate rock layers found mostly around Lake Huron. They are said to be over two billion years old. Shinarump is a conglomerate within the Colorado Plateau of Utah.

Because of the wide geography, demographics, and brand mix of its hotels and restaurants, each entity must be allowed much operational leeway in order to optimize for its unique local needs (culture, rules and laws, marketing strategies, etc.). However, this places a tremendous strain on an over-worked, central enterprise data warehouse team.

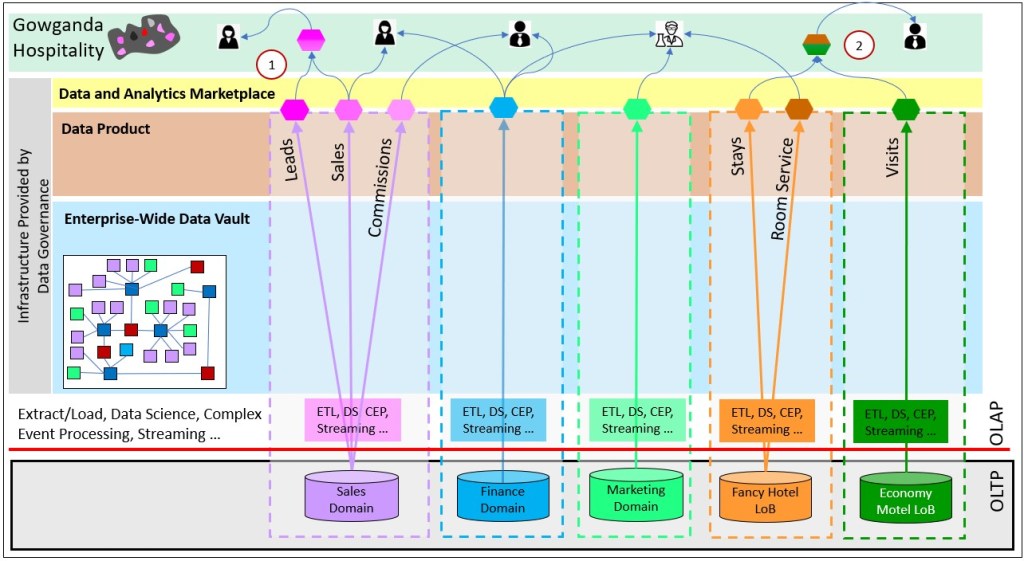

Figure 2 depicts a partial data mesh for Gowganda. The leftmost three domains are at the corporate level of Gowganda. Sales, Finance, and Marketing are typical “generic” domains of an enterprise. Meaning, they are ubiquitous among corporations, very similar, and not usually a core competency. However, in the case of Gowganda, the value-add is optimized administration of the hotels and restaurants. So these generic domains are kind of core.

For this blog, we will focus on the two rightmost entities of Gowganda Hospitality. They are just a sample of two of the hotels owned by Gowganda Hospitality. Each comes from different places with different demographics. Therefore, for the sake of success and painlessness, they should be allowed operate as independent entities:

- Fancy Hotel (FH) – A high-end hotel with an attached restaurant providing fine-dining room service for the guests. Located in a high-end neighborhood of Ann Arbor, MI.

- Economy Motel (EM) – A no-frills, lower-end motel. Located outside of Hurricane, UT, it’s just a place for visitors to Zion National Park to sleep.

The two entities are similar in that they are both hotels, but different enough where there is some level of friction when attempting to fuse the two hotels into a single composite view. So the hotels and restaurants are granted much leeway to cater to their unique situation.

In exchange for that freedom, each must provide analytics Data Products to the corporate analysts to:

- Monitor progress.

- Produce reports.

- Research what works and what doesn’t work under different conditions.

- Formulate new strategic suggestions (they are independently operated).

- Forecast revenue, budget, and profitability.

The quality, form, and content of the Data Products can vary. However, they must meet negotiated service level agreements (SLA) and service level objectives (SLO). Treat each domain data product like a service with clear targets:

- Freshness: 95% of rows available within 15 minutes of source event; 99% within 1 hour. (Batch case: ready by 06:00 MT daily.)

- Completeness: ≥ 99% of expected records per day; alert if count deviates by more than ±2% week-over-week.

- Schema evolution: Additive changes anytime; 7-day deprecation window for removals; semantic changes require a version bump and a published JSON contract.

- Quality: Critical-field null rate < 0.5%; duplicate rate < 0.1%; business-key uniqueness enforced.

- Availability (serving): 99.5% query availability during business hours for the published interface (e.g., Kyvos model / Snowflake view).

- Lineage & docs: Owner, SME, source systems, and transformation repo links are published; automated lineage is visible in the catalog.

- Access & privacy: Row/column policies defined; PII masked in shared products; audit logs retained 90 days.

- Incident policy: Status page update within 30 min; RTO 2h, RPO 15m for serving layer.

These SLOs turn Event-Stormed sticky notes into operational contracts—so when we map to Vault (Part 3), we know what to automate, monitor, and pre-aggregate.

Note that there are two number-coded items in Figure 2 pointing out two kinds of composite data products.

- This is a Composite Data Product merged from the Leads and Sales data products of the sales domain.

- This is a Cross-Domain Composite Data Product merged from Stays data product of Fancy Hotel and the Visits Data Product of Economy Motel.

Data Product Composition (Part 5) is the last topic of this blog series. Up until that topic, the blog is focused on the decomposition/distribution aspects of Data Mesh and Data Vault. Then we need to integrate them into wider views.

Event Storming to Domain Model

The development of a Data Mesh is an enterprise-scoped affair. Its purpose is to organize the jumble of an enterprise into a coherent map serving analysts and decision makers at all levels of responsibility.

Event Storming tears the enterprise into its functional pieces, then organizes those pieces into a model. This is much like how one, given the opportunity, would disassemble an F-35 fighter jet into its functional parts to figure out how it works. There would be some sort of CAD model of the F-35 built.

That F-35 CAD model, would probably be static though. Models such as F-35s are expected to serve for years. However, business models and relationships with partners, vendors, governments, and customers are in constant turmoil. So a model of a business must be malleable. Just as we need an updated model of any situation we’re in, we need the view of our business to reflect current conditions. Without a malleable model, we’re seeing things through an obsolete view.

Change

The idea of a domain model is that in this day of DevOps/CI/CD, the maintenance of data objects from schemas, to ETL code, to OLAP cubes is reflected from this domain model.

By change, this means incremental changes that are constantly happening across domains and outside parties. Drastic dinosaur extinction changes are a different story. For the context of this blog, change at the raw data vault means:

- When a new line of business is added, add satellites to the appropriate hubs.

- When a new field is tracked, add another column.

For the “Business Vault”, that really means the Data Products. They take the form of star/snowflake schemas, which are optimized subsets of the raw Data Vault.

The change of a raw data vault applies to the folks in the domains, not the analytics consumers. To some extent, as class methods or microservices shields users from ugly details of “how the sausage is made”, the Data Products shields the consumers from the ugliness that goes on in the domains.

Therefore, change within the data mesh applies to what is experienced by the data product consumers. That change can include additions at the data product level or entirely new data products. Any deletions or change in semantics of a column must be properly communicated, in stages of deprecation, as it would be for any other software product.

It might be tempting to discount the value of an event storming session if the business isn’t currently working well. We just intend to gut the whole thing and rebuild. But with real employees, real investors, real assets, it’s a matter of getting from Point A to Point B. We need to verify that the understanding of Point A is valid and not just a mythology of assumptions.

Event Storming

This wide-scoped version of event storming is most useful on a greenfield project, one where legacy OLTP systems are replaced, in part or even in whole. However, this is a good exercise anyway since it refreshes reality of what goes on in an enterprise.

Event Storming for a non-greenfield project may seem like overkill. But I’ve been in so many situations where some gotcha that could have been caught upfront seriously derailed a project. Obtaining an accurate model of the enterprise is the starting point for any serious endeavor towards becoming data-driven.

This is similar to how a complete inventory should occasionally take place. Over time, items are misplaced, stolen, miscounted, etc. The only way to ensure we know what we have is to periodically count from scratch.

It’s important to keep forefront in mind that this exercise is about the discovery of how things are working. This isn’t about design or reorganization of the enterprise. We need to map out where we are, then incrementally improve through the analytics system we’re designing.

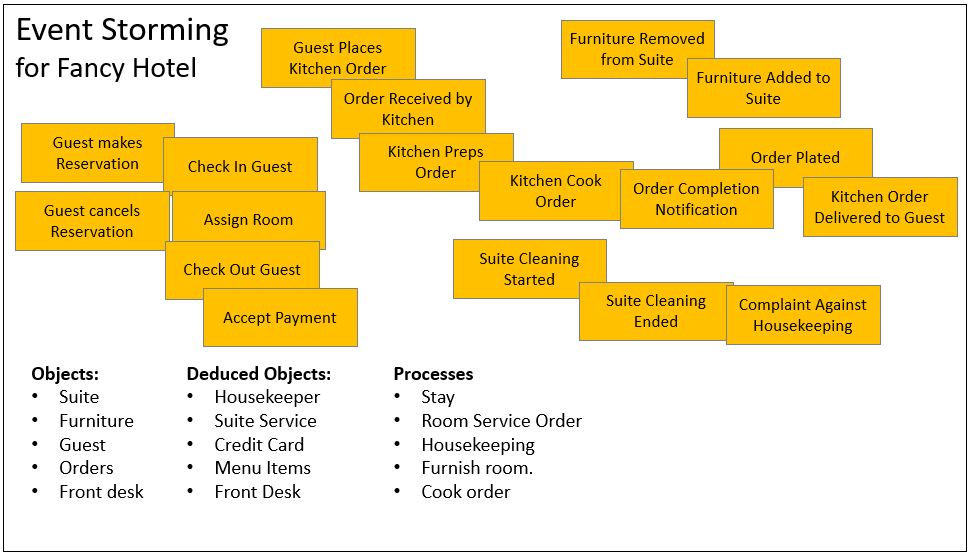

Figure 3a depicts the Event Storming session for Fancy Hotel. It serves as the basis for most of the rest of the journey from Event Storming to Data Mesh.

- List all events that happen in a business.

- Try to use past-tense.

- Try to phrase in subject-verb-object.

- Use the language of the information worker.

- Think about the possible outcomes of each event.

- Each outcome is itself an event.

- What are the expected outcomes and the unusual ones?

- Don’t worry about the order of the notes too much.

- This is a brain-storming session.

- The notes will be organized later by a smaller group.

- Don’t get too into the weeds at this time.

- We don’t want to spend inordinate time on a few issues.

- Business rules will be another step.

Notice in Figure 3a that the event notes are somewhat separated into groups – visit, room service, furnishing, and housekeeping.

Event Storming isn’t just documentation—it’s a stencil for the Vault you’ll build next. In practice:

- Events → Links. Each business event that relates things (e.g., “ReservationCreated”) becomes a Link with timestamps and payload.

- Things → Hubs. The nouns behind those events (Guest, Reservation, Room, Invoice) become Hubs with stable business keys.

- Changing details → Satellites. Attributes that evolve over time (rate, status, contact info) land in Satellites (Type-2 by default).

When we move to Part 3, translating your sticky notes to Hubs/Links/Sats is mostly mechanical—and amenable to metadata-driven automation.

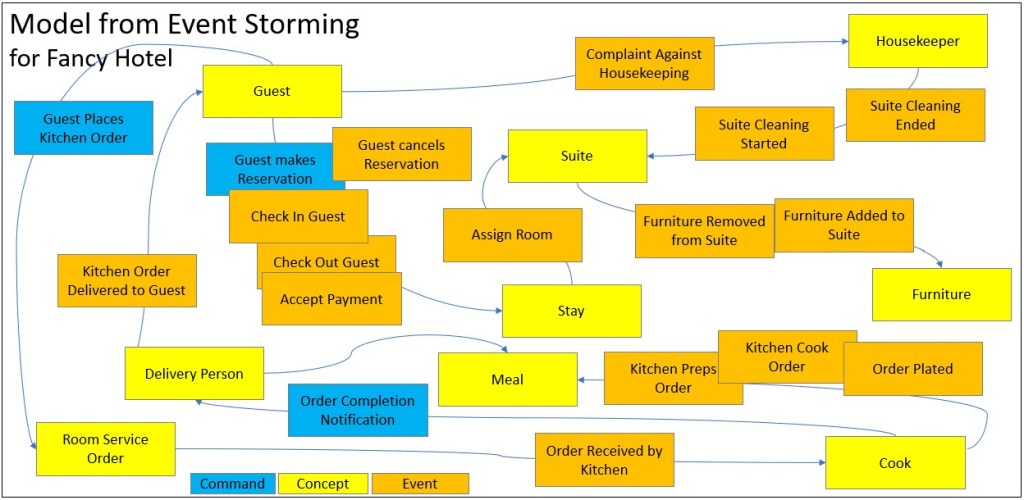

Figure 3c is a somewhat unorthodox domain model. Please note that Figure 3c is just a graphical visualization of the Domain Model for the purposes of this blog. In an upcoming section I describe using Python to encode the domain model.

- Domain-Driven Design is the decomposition of a complex system into manageable parts, followed by a methodical and loosely-coupled re-assembly of those parts.

- Hotel with attached Restaurant is the Domain.

- Bounded Contexts are in the dashed boxes.

- A bounded context is the way things are grouped as a solution.

- A Ubiquitous Language is the spoken by everyone within a Bounded Context.

- Subdomains are within the solid lines.

- Notice that the subdomain names are verbs (“…ing”).

- Subdomains involve groups of entities.

- Ex: Cooking involves chef, kitchen, assistants. Waiting involves waiter, customer, orders. Serving is the core domain.

- Cooking could arguably be a core domain.

- Accounting is a generic subdomain.

- Subdomains communicate with each other through consistent interfaces.

- Events are the communications through those interfaces.

The Events are ultimately pieced together into a model of loosely-coupled microservices. Additionally, entities that are involved with the events are identified.

Entities consist of attributes, columns in a table. Not all events (microservices) require all attributes.

Domain Model Encoding with Python

In my prior blog, DVM/DDD, I write about encoding the domain model with F#, a functional programming language. It’s a brilliant technique championed by Scott Wlaschin. The fundamental idea is that the characteristics of a system can be captured and readily understood by programmers, non-programmers, and machines.

However, the big problem with F# is that it’s yet another language to be learned. This isn’t so bad since the type system and function definitions are all that most members of a project team would need to know. So I wondered, could this work with Python? If one didn’t know how to program today or one has time to know just one language, Python is the most sensible language to learn and master.

In terms of the ease of understanding the type and function definition of F# and Python for non-programmers, my opinion is that an arguable edge goes to F#.

The strongly-typed aspect of F# is a major feature that makes it attractive for modeling domains. Python is mostly considered to be strongly-typed. One attractive aspect of it for use as a scripting language is that one didn’t need to worry about type errors. A programmer could be sloppy when you just wanted to quickly try something out.

The main idea in relation to Event Storming is that we separate behavior from data. This is contrary to object-oriented programming where the data and behavior of entities are encapsulated in a class. In a nutshell, entity data is defined in a class and all events between entities are defined in functions.

While this isn’t quite as clean as it would be with a primarily functional programming language, it’s good enough.

Beyond the massive popularity of Python, I think the biggest advantage of Python over F# in this case is that reflection is pretty much a 1st-Class feature of Python. Reflection is the name for a set of built-in coding features for examining the code itself. While such features exist for most modern programming languages (Java, .NET), the features are like add-ons. But for the dictionary-rooted Python, reflection is very natural.

The use case for reflection here is that we will generate code (ex. ETL objects, SQL, DDL) from the domain model encoded as Python. This is arguably the most important part of the blog. Without the automation of such code and processes, the idea of a data vault and data mesh generates a great deal of work for the poor human developers of IT.

The DevOps/CI/CD aspect of encoding the domain models with a real programming language is critical. Both Data Mesh and Data Vault tackle complexity by first making things seem more complicated.

Python will show up as the method to encode the data model assembled from the Event Storming session as well as the model for the Data Vault.

Figure 4b shows the Python function declarations for a few of the events.

Roughly, the function definitions represent a microservice. At least each is an individual API call.

© 2021-2022 by Eugene Asahara. All rights reserved.