Think about the usual depiction of a network of brain neurons. It’s almost always shown as a sprawling, kind of amorphous web, with no real structure or organization—just a big ball of connected neurons (like the Griswold Christmas lights). But this image misses so much of what makes the brain remarkable. Neurons aren’t just randomly strung together into a web; they’re organized into intricate components, each having emerged towards a special purpose. These structures integrate into our consciousness, something much greater than the sum of the parts.

Similar to how the models of the solar system we’ve grown up with are drastically out of scale, the scale of the depiction of neurons paints a misleading picture. The typical depiction shows a few dozen, maybe a few hundred neurons, as if that’s enough to represent what’s going on. Like with the model of the solar system, the depictions of neurons obviously aren’t intended to portray the entire brain. But it paints a very distorted image we hold.

In reality, there are about 80 billion neurons in our human brain, each with hundreds, more so, thousands of connections. And the neurons themselves aren’t these tidy, relatively abstract shapes you see in diagrams. Each is a vastly sophisticated unit, a living organism in their own right. Each is more reminiscent in shape of a maple tree pulled from the ground than an octopus—its roots represented by the sprawling dendrites that gather input from other neurons, its trunk and branches mirroring the axon that reaches out to send signals. It’s not just a network—it’s an ecosystem, a massive forest of activity that grows and adapts as it works.

What’s more, this organized forest of neurons doesn’t just spring into being fully formed; it self-assembles over years of constant exposure to stimuli and our need to comprehend and react. The scale of complexity is staggering—not just the sheer numbers, but the way these billions of elements coordinate to form something so structured, yet so fluid and dynamic.

But I’m not a neuroscientist or microbiologist, so I’m stepping well out of my lane. I’m just conveying what similarities I’ve noticed in those fields as a novice enthusiast to what I know—my lane of data engineering and business intelligence (BI). And how those insights could be of value to my fellow data engineers and BI enthusiasts.

So, switching to what I know better, I’d like to share some insights into how the structure of knowledge graphs (KG) should be more than a collection of nodes and relationships. There must be structure that partitions a KG into manageable, composable chunks that could be maintained in a loosely-coupled fashion.

This is where the Semantic Web (RDF, OWL, SPARQL), for all its achievements in ensuring shared meaning, falls somewhat short. It focuses on standardizing the meaning of classes, terms, and relationships so that different parties interpret them consistently—a critical foundation for interoperability. But it says little about the structure of how those elements are organized. A semantic agreement that “Human is a class, and Eugene Asahara is an instance of a human” is valuable, but it doesn’t guide how to architect a system where one’s relationships to other nodes—like a car, a business, or an event—are modular, scalable, and maintainable.

In essence, semantics ensures everyone speaks the same language, but structure dictates how the conversation is organized and how effectively it can scale to complexity. Without this structural organization, KGs risk becoming sprawling webs that are impractical to manage. A truly effective KG needs more than shared meaning; it needs a coherent, functional architecture.

KGs have been around for a few decades. The gotcha is that they are incredibly difficult to author by human experts alone. Even the best experts will find great difficulty in expressing the depth of their subject matter expertise in a symbolic graph.

KGs are even harder to maintain as things in the knowledge space relentlessly change. It seems like most forgot all about the semantic web KGs until the recent renewed interest in how it can work symbiotically with LLMs. Even two years ago, most of my colleagues hardly knew anything about them. So, the big problem has always been, how can the KG self-assemble as much as possible. With the maturity of data platforms, KG authoring tools, machine learning platforms, and the advent of LLMs, a good chunk of KG development can be automated.

I wrote about a similar situation with Prolog in, Prolog and ML Models – Prolog’s Role in the LLM Era, Part 4. That is, merging functions (ML models are functions) into KGs.

Here is a rough outline of what we’ll cover:

- Tightly-Coupled vs. Loosely-Coupled: Monolithic systems vs. loosely-coupled systems.

- G Major Chord – The reason why I’m thinking about this.

- Bridging Recognition and Symbols – The symbols of a KG are just symbols.

- Instances, Classes, Relationships – Backbone of KGs.

- Simple ML Models – Small ML models in a KG refine relationships, validate facts, and provide targeted predictions. Unlike monolithic AI, they are modular, interpretable, and adaptive within a structured system.

- Mini Neural Networks – I say “mini-NN” to distinguish them from LLMs, which are essentially neural networks but not mini in any way—mini-NN recognizing basically one thing, with thousands to millions of parameters, unlike LLMs, which operate on billions to trillions across many domains.

- The KG Alone is Just the Puppet

This blog covers just data structure. This is just an introduction to what should be a book or at least a series such as my earlier Prolog in the LLM Era. Another blog is needed to discuss the system for using the data structure.

Lastly, this blog is related to one of the two sessions I’m delivering at the Data Modeling Zone 2025 from March 4-6, 2025 in Phoenix, AZ. See the LinkedIn Page for DMZ2025 as well.

Tightly-Coupled (Big Ball of Mud) vs. Loosely-Coupled System

In this era of LLMs, the spotlight is firmly on massive, monolithic models like ChatGPT, Gemini, and Grok. When ChatGPT caught the attention of the general public back in November 2022, the pitch was that simply scaling up the “parameters” (from millions to billions to trillions) and the training data would eventually result in artificial general intelligence or even super intelligence emerging from the muck.

Today, we know that’s not right. It will likely take much more than simply scaling parameters and volume of training data to ridiculous heights before some magic light switches on in these LLMs. We naturally forget in every iteration of “the next big thing” that things come in s-curves, where we reach a point of diminishing returns, not hockey sticks where the line goes up through the sky forever.

These LLM models, with their ability to “know more about more things” than most individuals, are undeniably revolutionary. Yet, there’s something fundamentally unsettling about this monolithic approach. It feels like a throwback to an era of monolithic, tightly-coupled systems that the software industry has worked so hard to outgrow—embracing paradigms like object-oriented programming, domain-driven design, microservices, functional programming, and, more recently, data mesh to create distributed, loosely coupled, and componentized architectures.

The appeal of loosely-coupled distributed systems lies in their maintainability and resilience. By partitioning development and maintenance along functional or domain-specific boundaries, changes can be isolated, reducing the risk of the dreaded “fix one thing, break two things” syndrome that plagues monolithic systems. With modular components, each part of the system remains cohesive, comprehensible, and more readily adaptable. But in contrast, monolithic systems like LLMs are dangerously opaque—giant tangles of parameters and relationships, beyond the understanding of any individual developer or team.

Yet, it’s impossible to deny the value LLMs bring. Their sheer breadth of knowledge and their ability to synthesize and generate language make them unprecedentedly powerful tools. They’re like that know-it-all friend who can provide answers on almost any topic—helpful, but still not the solution to every hard problem, nor the pinnacle of efficiency or clarity.

This blog explores an alternative approach: supplementing monolithic LLMs with many (possibly swarms) of smaller, more conventional, domain-specific neural networks embedded within a KG. By grounding mini-neural networks in a well-structured KG, we can create systems that are not only smarter but also easier to maintain, adapt, and scale.

Along the way, we’ll also examine how KG constructs—like “is a,” “has a,” and “a kind of” relationships—can be enhanced by ML models, bridging the gap between symbolic reasoning and statistical learning. This adds an element of “modular self-assembly”. By that I mean discrete chunks of a KG can reliably and deterministically update itself with statistics-founded ML models.

With that very basic understanding of what I’m shooting for, I want to share a story of the genesis of my interest in the notion of placing structure in the KG.

The G Major Chord: Bridging Recognition and Symbols

During my work over the past couple of decades with symbol-oriented technologies such as Prolog, knowledge graphs, and finite state automata, I’ve often thought of the somewhat arbitrary labels we apply to things and concepts. For example, the symbol “Red” (literally the string of three characters or as a bunch of lines that happen to resemble that sequence of letters) corresponds to a specific frequency range of light (roughly 620–750 nanometers in wavelength). But we generally communicate the notion of “Red” to each other using those three letters or the sound of that word through our mouths. Neither method has anything to do with its real nature, light.

Let’s explore the example of a G Major Chord. It’s not just a symbol in a database—it’s actually a physical phenomenon with specific and measurable properties. We could state in words:

“The G major Chord is made up of the G, B, and D notes, where B is its 3rd and D is its 5th.”

As (reasonably) accurate and descriptive as that previous sentence might be, it certainly isn’t anything like the G major chord generated by a musician and heard with our ears. As I repeat that sentence describing G major in my head, it doesn’t sound anything like the iconic G major opening chord of the Eagles’ “Take it Easy”.

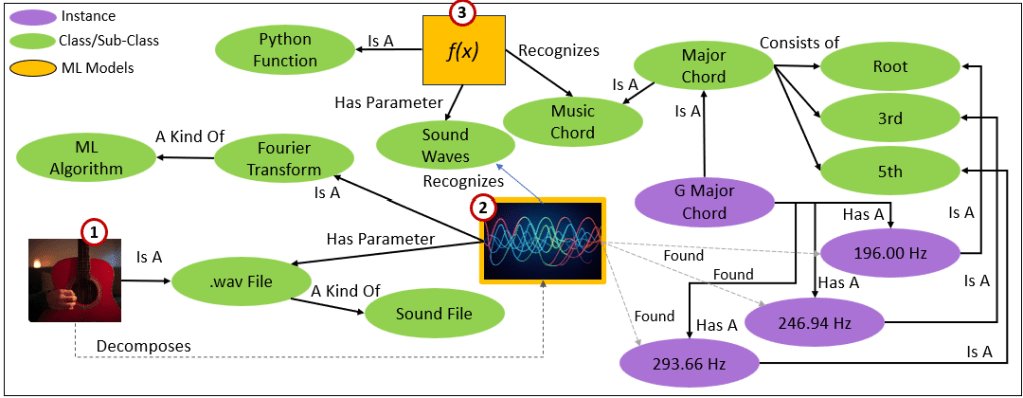

KG nodes and relationships will always be too high-level and abstract to truly reflect the world. What is a step closer to reality than that sentence describing a G major is a Fourier Transform, a kind of ML model, that analyzes a sound captured in a .wav file, decomposes the sound, and determines if it finds the frequencies (196, 246.94, and 293.66 Hz- G, B, D, respectively) that make up the G major chord.

We see that process illustrated as a self-explanatory KG segment in Figure 2. This process highlights how physical data (frequencies) is transformed into meaningful symbols in the KG, creating a bridge between the physical and symbolic worlds.

Below is an explanation of the three items marked in Figure 2:

- This is the source file that is analyzed (Decomposed) by the Fourier Transform.

- A Fourier Transform model that decomposes sound into constituent frequencies—196.0, 246.94, and 293.66, which comprises a G Major chord.

- A Python function that takes in a set of frequencies and determines if the set composes a G major chord. This function isn’t an ML model since what determines a G major chord is a specific rule. So the function can be written and deployed using a conventional programming language such as Python – or Prolog as I suggest in Prolog in the LLM Era.

Now that we have an intuition for the purpose of this blog, with even more ado (haha), I’d like to digress a bit to explain the very basics of knowledge graphs–specifically the basics of taxonomies and ontologies.

The Backbone of Knowledge Graphs: Instances, Classes, and Relationships

KGs are emerging as a cornerstone of how we organize and deterministically structure information. Much of the KG’s renewed popularity is driven by the emergence of powerful LLMs. As I explain in my book, Enterprise Intelligence, KGs have a powerful symbiotic relationship with LLMs. In a nutshell, KGs provide the deterministic structure and precision that LLMs often lack, acting as a grounding framework to validate and contextualize LLM outputs. Meanwhile, LLMs extend the reach of KGs by filling in gaps with probabilistic reasoning and offering context-rich insights that a KG alone might struggle to produce.

It’s like Mr. Spock and Captain Kirk. Together, they form a complementary system—KGs anchoring the LLM in accuracy and consistency, while the LLM enhances the KG with broader, more nuanced understanding. This interplay creates a feedback loop where the KG becomes more robust and the LLM more precise, driving a deeper integration of knowledge and reasoning.

At their core, KGs are about connecting things—concepts, objects, events, or people. But it’s not just the connections that matter; it’s the nature of those connections that gives KGs their power. These relationships and the nodes they connect mirror how we think about and navigate the world.

To understand this, we need to consider two foundational ideas: taxonomy and ontology.

Taxonomy is about classification. It provides a hierarchical structure, organizing things into nested categories, much like a tree. For example, in a taxonomy, we might classify “Dog” under “Mammal,” which is itself under “Animal.” Taxonomies are useful for understanding broad relationships and for navigation—think of how a library catalog works.

Ontology, on the other hand, is about understanding the deeper semantics of those relationships. While a taxonomy might tell you that “Dog” is a kind of “Mammal,” an ontology extends this by defining properties, rules, and interconnections—like “Dogs are loyal,” “Mammals have fur”, or “Humans own pets.” Ontologies make KGs more than just a structured list; they make them an interconnected web of meaning.

When we talk about a KG, we’re typically dealing with two key types of nodes: classes and instances.

- Classes are the broad categories or types, such as “Human” or “Car.”

- Instances are the specific, real-world examples of those classes, like “Eugene Asahara” (a human) or “My Ford Flex” (a car).

The edges connect these nodes, they are the relationships between nodes. These edges encode everything from simple hierarchies (“is a kind of”) to specific attributes (“has a”) or even equivalences (“is”). Together, they transform a KG from a static structure into a dynamic system capable of reflecting the richness of the real world.

Here is a breakdown of the essential relationships in a KG, focusing on the ones that matter most when integrating AI and symbolic reasoning:

“is a” (Instance of a Class)

This relationship connects a specific instance to a general class. It’s a basic but vital link because it tells us what category an individual belongs to.

- Example:

Eugene Asaharais a Human.

In KG terms:EugeneAsahara rdf:type Human.

“a kind of” (Subclass of a Class)

This one is about how classes relate to each other. It’s a hierarchy: one class is a more specific version of another.

- Example:

Caris a kind of Vehicle.

In KG terms:Car rdfs:subClassOf Vehicle.

“has a” (Properties or Attributes)

These relationships describe the properties or components of a node. They answer questions like “What does this entity have?” or “What are its characteristics?”

- Example:

EugeneAsaharahas a Car.Humanhas an Arm.

“is” (Equivalence or Identity)

This relationship declares that two nodes are essentially the same thing. It’s about equivalence, synonyms.

- Example:

Automobileis Car (different terms for the same concept).

In KG terms:Automobile owl:equivalentClass Car.

“related to” (Associations and Contexts)

This is a looser, catch-all category for relationships that don’t fit neatly into the others. It can include correlations, causal links, or broader connections.

- Example:

EugeneAsaharais related to Programming.

Table 1 summarizes those relationships into a nice table.

| Relationship | Description | Example | KG Term |

|---|---|---|---|

| “is a” | Instance of a class | EugeneAsahara rdf:type Human | rdf:type |

| “a kind of” | Subclass of a class | Car rdfs:subClassOf Vehicle | rdfs:subClassOf |

| “has a” | Properties or attributes of a node | EugeneAsahara hasCar E_Ford_F150 | Object or Datatype Property |

| “is” | Equivalence between nodes | Automobile owl:equivalentClass Car | owl:equivalentClass |

| “related to” | Loosely associated, broader contextual relationships | EugeneAsahara relatedTo Programming | Custom or rdfs:seeAlso |

Why These Relationships Matter in AI Frameworks

These relationships aren’t just for organizing information; they’re the scaffolding for reasoning. When a neural network recognizes a cat, a KG can expand that recognition into a web of taxonomic and/or ontological meaning: a cat is a kind of feline, which is a mammal, which has properties like fur and whiskers, and cats are predators. This symbolic layer complements the pattern-matching prowess of AI, making the system both smarter and more explainable.

The relationships in a KG aren’t just abstract connections—they’re the threads that weave together our understanding of the world. By capturing the nuances of these relationships, we can build AI systems that don’t just recognize patterns but also reason, explain, and adapt. And as we’ve seen, even the simplest relationships—like “is a” or “has a”—can become profound tools when combined with AI-driven insights.

Remember that the KG is a primary component for us humans to input our structured knowledge and intentions into AI systems. It represents our understanding of the world—what we define, classify, and connect—serving as the foundation on which AI reasoning is built. Ideally, LLMs should complement KGs, not the other way around. LLMs can enhance KGs by filling in gaps with probabilistic reasoning, but the KG remains the grounding framework, ensuring consistency, accuracy, and transparency.

What I’m proposing is that it’s OK to automate at least some parts of the KG with ML models we’ve built with our grubby hands. By embedding human-supervised ML models directly into the KG or linking to their outputs, we can create a dynamic feedback loop. The KG becomes not only a representation of human knowledge but also an evolving, semi-automated system that incorporates reliable AI insights without compromising the integrity or structure of the graph. This integration of human-curated KGs and trustworthy AI offers a scalable path toward more intelligent and adaptable systems.

Is, Is A, Has A with Simpler ML and Master Data Management

Before diving into neural networks and more complex ML models, it’s essential to recognize how simpler models—like clusters, associations, or basic rules—fit naturally into the traditional taxonomies and ontologies of KGs. These simpler models can often be serialized directly into the KG, forming the backbone of an AI system’s reasoning capabilities. By integrating the rules of such models as attributes or relationships, these models make the KG not just a static store of knowledge but an active reasoning framework.

At least at the time of this writing, such models are primary built (or at least guided by) a cross-functional team of subject matter experts, business stakeholders, data scientists, and data engineers. The team creates a hypothesis that is a set of attributes they believe affect a customer’s choices. But an ML algorithm plays more of a role in selecting the best combination of attributes and how much each matter.

“Is” Relationships in MDM

The “Is” relationship is a cornerstone of Master Data Management (MDM), a discipline that has been around for decades and serves as a pillar of data governance. The central goal of MDM is to create a “master record” for key entities, resolving duplicate or fragmented representations across disparate systems. For example, in an organization with multiple databases, the same customer might be represented in one system as “Customer ID 12345” and in another as “Eugene Asahara.” Establishing that “Customer ID 12345 is Eugene Asahara” creates a unified view of the customer and facilitates accurate reporting, analysis, and operational efficiency.

MDM is inherently labor-intensive, involving the painstaking reconciliation of records from various systems and consensus from multiple parties. Traditionally, this process relied on manual reviews and static rules to identify matches and consolidate records. However, today, ML plays a significant role in automating MDM tasks, significantly reducing the effort required. For instance, ML models can analyze patterns in names, addresses, and transactional histories to predict whether two entities in different systems represent the same thing. This enhancement has transformed MDM from a static, rule-based practice into a more dynamic and scalable approach.

For KGs, MDM-style “Is” relationships align perfectly with their structure. These relationships resolve ambiguities, eliminate redundancies, and provide a consistent foundation for building ontologies and reasoning systems. Examples of “Is” relationships in MDM could include:

- “Product A in System 1 is Product B in System 2.”

- “Invoice #9876 is Billing Record #12345.”

- “Customer ID 12345 is Eugene Asahara.”

By encoding these equivalence relationships directly into the KG, the graph becomes a more unified and reliable source of truth across organizational systems. These synonyms mapped through MDM rectify ambiguity between terms from different domains and ML models. They are the transformers between the output of an ML model to the input of another ML model.

“Has A” of Association Rules

Beyond “Is” relationships, simpler ML models like clusters and associations provide rules and structures that align seamlessly with KG taxonomies. These models offer lightweight, interpretable insights that can be directly embedded into the KG, making them a natural complement to the more static structures of MDM.

For example, Figure 3 illustrates an association model that identifies rules such as:

“Customers who have no recent bookings, filed complaints, and have no activity on their loyalty program will leave.”

These items are encoded in Figure 3 as:

- This is an ML model that recognizes the attributes of a customer about ready to leave.

- The ML model is an association role (a.k.a. market basket).

- These are the attributes that comprise a customer that’s probably about to leave your services.

This rule fits neatly into a “Has A” structure in a KG. Associations like this are not only useful for reasoning but also inherently compatible with the way KGs organize relationships.

“Is A” of Cluster Models

Cluster Models classify a set of “things” into categories they determine in a data-driven manner. Figure 4 demonstrates how clustering algorithms (1) segment customers into categories like “Luxury Buyers,” “Value Shoppers,” or “Impulse Shoppers” (2). These clusters form “Is A” relationships with individual customers (3), linking them to broader groups and enabling reasoning within the KG. For example, a node for Louis XIV might have an “Is A” edge connecting him to the “Luxury Buyers” cluster.

Note that the nodes comprising the cluster model (4) can be updated as a whole when the Customer Cluster model (1) is updated. Of course, the customers need to be re-run through the cluster model and connected or (re-connected) to their calculated cluster (5).

These types of ML rules are relatively lightweight in terms of complexity and computationally manageable, making it feasible to serialize the rules directly into the KG. They provide structure and insight that align perfectly with the KG’s purpose of organizing knowledge and reasoning over it.

The Definitions of the Model Rules

When discussing the rules produced by ML models, it’s important to note that not all rule definitions or metadata are readily feasible for embedding directly into a KG. Simpler models, like clusters or association rules, generate definitions and rules that are tightly tied to their purpose and relatively lightweight. For instance, in association models, each rule often corresponds to a “Has A” relationship in the KG, with metadata such as confidence scores or support levels easily serialized as attributes on those relationships. Similarly, in cluster models, the clusters themselves are well-defined categories (“Is A” relationships) that can be directly represented within the KG.

However, for more complex ML model types, the feasibility of embedding their rules and definitions can be challenging and even unnecessary. For example, models like deep neural networks or Fourier transforms have intricate definitions that involve countless parameters (ex. millions of weights in a neural network). These “innards,” while crucial for the model’s operation, are too computationally dense and abstract to be meaningfully serialized within the KG. Instead, these models are better handled through references or pointers. For instance:

- Deep Learning Models: A neural network trained to recognize mammals might be serialized as an ONNX file. The KG node could include a pointer to this file’s storage location, along with metadata about the model (ex., input/output parameters and purpose). The low-level of reality doesn’t fit into a KG, but somehow it needs to.

- Fourier Transform Models: For models that process audio signals, such as recognizing musical chords, the KG might store the results (ex. “Has A” relationships linking sound files to recognized chords), while pointing to the external file containing the serialized model used for recognition.

Decision forests occupy a middle ground. The rules of a decision forest—often derived from a relatively small number of parameters and hyperparameters—can sometimes be serialized into a KG, with each rule node representing a branch or leaf in one of its many trees. In fact, decision forests materialized as a web can be quite intriguing to look at. These serialized rules could include attributes such as the threshold values used for splits or the features that guide the tree’s decisions. Because of their limited complexity, decision tree rules often lend themselves to direct KG integration.

By adopting this hybrid approach, where simpler models are directly serialized into the KG and more complex ones are referenced in the KG but stored externally, the KG retains its efficiency while enabling access to specialized computational power. This balance ensures that the KG remains a practical and flexible reasoning system while supporting a broader range of ML models and their outputs.

Knowledge Graph Integration: Organizing Recognitions

Let’s focus now on neural networks. In this case, I’m referring to neural networks targeted at specific classification tasks—for example, recognizing a cat, identifying a tumor, detecting early signs of a hurricane, or diagnosing an assembly line machine that is about to fail. Depending on the quality of the training material, neural networks can recognize its target under highly variable conditions—angle, orientation, lighting, within a lot of “noise”.

Each such neural network functions as a standalone system, taking in specific parameters and returning a defined output. The input parameters and output are its “contract” to the world. How the mapping from inputs to outputs is achieved doesn’t matter to the rest of the system (a black box) as long as the rules of functions are abided (ex. no side effects, deterministic output for the same input, etc.).

Because each neural network is a self-contained unit, it can therefore be developed, trained, and maintained independently. This contrasts with LLMs, which are massive, monolithic structures that can produce different, sometimes bizarre, responses for what seems like the same input.

With that said, I’ve been a big fan of On Intelligence by Jeff Hawkins since its publication in 2004. Around that time (2005), I was working on the foundation for a Prolog-based system. In that book, Hawkins explored the structure of the neocortex and introduced the idea of cortical mini-columns. It recognized then that each mini-column resembles an individual neural network. The neocortex is essentially a highly interconnected field of mini-columns, where the outputs of some serve as inputs to others in a vast, distributed system-see Note 1 at the end of this blog.

Back in 2005 when I was working on my Prolog-based system (SCL), training even a single neural network was more than most organizations could stomach. The barriers included acquiring sufficiently labeled training data, having adequate hardware, and working with tools that were not yet user-friendly or accessible to non-experts. These hurdles made practical implementation prohibitive for most of my customers at the time.

Today, the landscape is very different. Data is abundant, hardware is powerful and affordable, and tools like TensorFlow, PyTorch, and even services like the Azure AI platform make building and deploying neural networks much more feasible—often even without an undergrad degree in machine learning or statistics. This democratization of AI tools has opened up exciting possibilities, including enabling the rise of KGs as an organizing framework for integrating neural networks into larger systems.

In this framework, mini neural networks (mini-NNs—as I mentioned, to differentiate from massive LLMs) can specialize in tightly-scoped recognition tasks, such as:

- Detecting objects in images (ex. recognizing cats in photos, which is often performed by convolutional neural networks, or CNNs).

- Identifying patterns in audio files (ex. troubling noises, which could be analyzed by recurrent neural networks, or RNNs, or newer attention-based architectures).

These mini-NNs serve as the recognition layer of the system, detecting patterns in real-world data, perhaps even real-time data, and passing those results into the KG. The KG acts as the organizational backbone, linking mini-NN outputs to semantic ontologies and taxonomies.

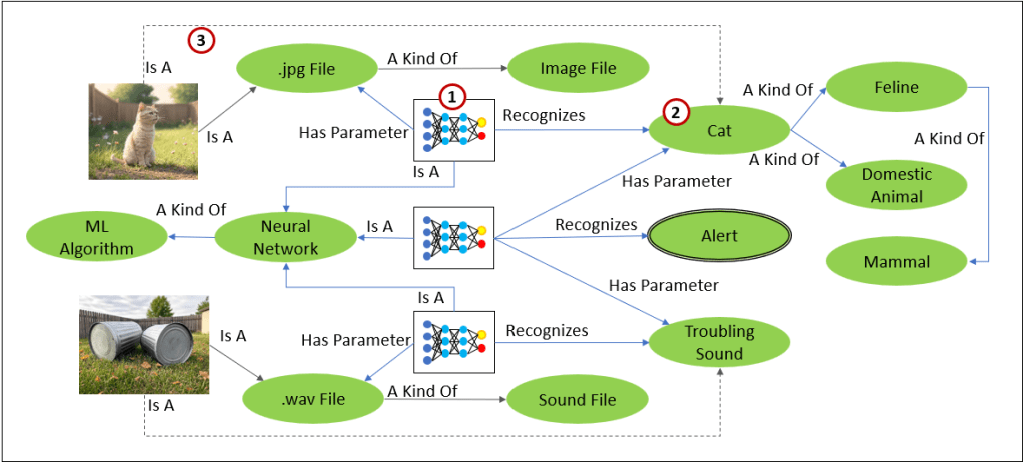

Figure 5, illustrates the basic pattern of how mini-NNs for images and sounds can be embedded into a KG. It’s two mini-NNs feeding into 2nd level NN:

- mini-NN: An array of neural networks embedding into the KG. Each specifies:

- What is recognizes (its output).

- Its set of parameters (its input).

- A pointer to the file where its serialized rules and metadata are located (not shown in Figure 5).

- Recognitions:

- An image file (.jpg) is processed by a mini-NN and classified as a “cat.”

- A sound file (.wav) is processed and identified as a “troubling sound.”

- Mapping to Ontologies: Recognitions are tied to nodes in the KG, enabling richer reasoning:

- “Cat” connects to its taxonomy: feline → domestic animal → mammal.

- “Troubling sound” links to an “alert” system.

Each mini-NN specializes in recognizing specific features or patterns, in this case, identifying a “cat” in an image file and detecting a “troubling sound” in an audio file. The KG then contextualizes these recognitions, linking them to the semantic ontology of concepts and relationships. For example, the recognition of a “cat” is connected to its taxonomy (feline → domestic animal → mammal), and the detection of a “troubling sound” is tied to an “alert” system.

To drive the point home, consider the AI systems currently used in healthcare to automatically analyze x-rays and other medical images. For instance, an AI trained to detect prostate cancer. In a KG, we might see a node for the ICD-10 code corresponding to that diagnosis, along with relationships stating it is “a kind of cancer” and linking it to related concepts.

However, the AI model—likely a neural network—trained to analyze x-rays and detect prostate cancer could arguably represent a more nuanced “definition” of prostate cancer than a dozen or so nodes with textual labels in a KG. It encapsulates not only the conceptual relationships but also the patterns and characteristics present in real-world data that define the disease—in a way beyond what can be said with words.

If you look at the green nodes (ordinary KG nodes) extending from the neural network nodes in Figure 5, they’re like the axons extending outward, connecting the outputs of the neural network to other concepts in the KG as well as to other neural network nodes. Meanwhile, the parameters of the embedded neural networks are like dendrites receiving information.

Why Mini-NNs and KGs Work Well Together

The synergy between mini-NNs and KGs creates a scalable and adaptable data framework for reasoning:

- Specialization and Modularity: Mini-NNs are like mini-columns in the brain—specialized units that handle specific tasks.

- Each mini-NN can focus on a narrow domain (ex. identifying chords, recognizing objects).

- Interpretable Outputs: The integration with KGs ensures that every recognition is mapped to a meaningful context, making decisions transparent.

- Scalability: Adding new recognitions (ex. recognizing a new object) only requires training a new mini-NN, without retraining the entire system (as it is with LLMs).

- Bridging the Physical and Symbolic: Physical data (ex. frequencies, pixels) is abstracted into KG symbols, creating a bridge between real-world observations and abstract reasoning.

The KG/NN as a Database, Not the Intelligence

The approach I’ve described so far—using mini-NNs for tasks like recognizing a cat in an image or detecting troubling sounds in audio—is intended to naturally fit into current Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) systems. This is where things start to get really interesting, as the KG and NNs work together to form the database of an AI system that’s dynamic, contextual, and deterministic.

It’s important to reiterate that the KG/NN isn’t the intelligence itself—no more than your brain sitting in a bottle is intelligence. It’s a sophisticated, knowledge-driven database that stores, updates, and organizes recognitions. The intelligence lies in the AI system that queries it and takes action on the feedback, applying reasoning, decision-making, and action to bring the data to life—it’s more like the puppet, while the system using it is the puppeteer.

The KG/NN isn’t “thinking” or “deciding” on its own—it’s providing the raw materials for the AI system to act upon. In this way, the KG/NN is symbolic of the world, but it’s the system using it that brings it to life.

While this system isn’t “agentic AI” in the sense of being fitted with fully autonomous, goal-driven behavior, it provides a foundation for smarter agent-like systems. By dynamically querying the KG, the system gains contextual awareness and can make decisions based on real-world insights. To move closer to agentic AI, additional layers like reinforcement learning (RL), feedback loops, and goal-oriented planning could be integrated.

This approach reflects the ongoing evolution of AI systems. It combines:

- Symbolic Reasoning (KGs): Providing structured, explainable knowledge and relationships.

- Sub-symbolic Learning (NNs): Detecting patterns and adding real-world data to the KG.

- Dynamic Reasoning (RAG): Querying the KG/NN system for contextually relevant information in real-time.

Business Intelligence Example

This setup illustrates a very simple multi-level machine learning pipeline, where outputs from one model become critical inputs to another, enhancing the system’s ability to generate tailored and effective insights. It highlights the modular and interconnected nature of ML models embedded within a knowledge graph:

- Data Flow: The process starts with raw data in a JSON file (Step 1), which is parsed and contextualized into customer-specific parameters (Steps 2 and 3).

- Model Chaining: The first neural network predicts the churn risk (Step 4), and the output serves as an input to the second model, which calculates the coupon amount (Step 5).

- Actionable Output: The final output, a recommended coupon amount, is used to take action (Step 6), closing the loop between analysis and business impact.

Here is the description of Figure 6:

- The figure starts with a JSON file containing flexible-schema data. This file acts as a source of customer data, representing information in a machine-readable format. It contains parameters or attributes related to a customer, such as transactions, loyalty status, or other key indicators.

- The JSON parser processes the JSON file, extracting the relevant fields or parameters for further analysis. This step translates the raw JSON data into structured attributes that the system can use. These attributes include flags like “No Recent Bookings,” “Complaints,” and “Loyalty Program Inactive,” which serve as input to the machine learning model in Step 4.

- The extracted parameters are related to a specific customer instance, “Customer 123,” which is classified as part of the “Customer” class. This customer is further associated with specific attributes such as “Highly-Valued” (based on metrics like purchase history or loyalty) and “Large” (likely referring to purchase volume or other size metrics). These classifications help contextualize the customer within the system.

- A neural network model analyzes the parsed parameters (“No Recent Bookings,” “Complaints,” “Loyalty Program Inactive”) to predict whether “Customer 123” is at risk of churn. The output of this model is the “Churn Customer” classification, which identifies the customer as a high-risk individual likely to stop engaging with the business. This output becomes an input parameter to the next stage of the system.

- The output of the churn detection model (i.e., “Churn Customer”) is fed into another neural network. This second model is trained to determine the appropriate coupon amount that should be offered to the customer to mitigate churn risk. This decision could be based on parameters like the customer’s value level, purchase history, or specific risk factors associated with their potential churn.

- The final output of the second NN is the coupon amount. This value is presented as a node in the knowledge graph, representing an actionable decision derived from the insights produced by the models. The system could then use this coupon recommendation to personalize marketing efforts, retain the customer, or drive engagement.

Leveraging Publicly Available Neural Networks

KG objects and relationships can be “universally” recognized by unique IDs supplied by various organizations offering publicly available ontologies that help us to standardize objects. For example, DBPedia, SKOS, FIBO, etc. However, there exists libraries of neural networks for that recognition of a wide range of objects, for example: Hugging Face Models, PyTorch Model Zoo, and Open Model Zoo. Could these models be used as universally recognized “resources” as well as the resources cataloged by the Semantic Web ontologies?

Let’s try this another example to see how this might work—recognizing sassafras tree branches. The sassafras tree (Sassafras albidum) is a species that is fascinating to me—native to eastern North America, known for its root beer aroma, and multiple types of leaves simultaneously existing (left-hand mitten, right-hand mitten, three fingers, and a normal leaf). In a KG, we might define ex:SassafrasTree and ex:Branch like this in RDF Turtle:

@prefix ex: <http://example.org/ontology#> .

@prefix rdfs: <http://www.w3.org/2000/01/rdf-schema#> .

ex:SassafrasTree a ex:Plant ;

ex:hasPart ex:Branch ;

rdfs:label "Sassafras Tree" .

ex:Branch a ex:PlantComponent ;

rdfs:label "Branch" .

Similar to previous examples, we’d like a neural network that recognizes sassafras tree branches in images—say, to distinguish their stout, upward-curving structure from other trees. Current repositories like Hugging Face or TensorFlow Hub offer a slew of pre-trained models we can tap into. For this, let’s use microsoft/resnet-50, a ResNet-50 model from Hugging Face, which is built for image classification and could be fine-tuned to identify sassafras branches. We’ll embed it as a node in our graph:

ex:SassafrasBranchDetectorNN a ex:NeuralNetwork ;

ex:purpose "Recognize sassafras tree branches in images" ;

ex:inputType "Image" ;

ex:trainedOn ex:ImageNetDataset ;

ex:recognizes ex:Branch ;

ex:appliesTo ex:SassafrasTree ;

rdfs:seeAlso <https://huggingface.co/microsoft/resnet-50> .

This is a line by line description of the RDF above:

- ex:SassafrasBranchDetectorNN is our neural network node, uniquely identified.

- ex:purpose and ex:inputType clarify its function and requirements.

- ex:trainedOn points to ImageNet (a broad dataset; in practice, you’d fine-tune it with sassafras-specific images).

- ex:recognizes links it to the ex:Branch concept.

- ex:appliesTo ties it specifically to ex:SassafrasTree.

- rdfs:seeAlso provides the URL to the actual model, making it actionable.

With that neural network defined as a node in the KG, we can connect the neural network to the tree:

ex:SassafrasTree ex:analyzedBy ex:SassafrasBranchDetectorNN .

With this, the neural network becomes a structured part of the KG. Querying “what recognizes sassafras branches?” would return ex:SassafrasBranchDetectorNN, along with its URL (https://huggingface.co/microsoft/resnet-50), ready for use. This isn’t just a model floating in a repository—it’s a node with context, linked to a specific species and component. It bridges symbolic knowledge (the graph) with neural recognition, making it both interpretable and functional.

This is a simple case, but the approach scales. Think about:

- A forestry graph with ex:TreeBranchClassifierNN linked to multiple species.

- Metadata like training accuracy or branch-specific features (ex. curvature, bark texture) enriching the node.

- URLs pointing to specialized models in PyTorch Model Zoo or Open Model Zoo.

Repositories like Hugging Face provide the building blocks—models with URLs and metadata. The leap is structuring them into a knowledge graph, where a URL like https://huggingface.co/microsoft/resnet-50 isn’t just a link but a node with semantic weight.

For now, pointing to https://huggingface.co/microsoft/resnet-50 as a node is a practical start. It’s not a perfect URI in ontology terms, but it’s a real anchor you can download and fine-tune. My vision is a system where every neural network has a semantic identity, fully woven into our KGs—like branches on a sassafras tree—along the lines of neocortex mini-columns described by Jeff Hawkins.

Conclusion

One of the great promises of KGs is their ability to connect structured, semantic representations with the messy, unstructured real world. Yet, while public ontologies have made significant strides in organizing and classifying domain knowledge, they often remain static—limited to text, logical relationships, and curated data. To unlock their full potential, organizations could take a step forward by linking their ontologies to neural networks trained on domain-specific sensory inputs like images, audio, and video.

This approach addresses a fundamental limitation of purely semantic systems—their reliance on human-readable or pre-structured data. Some concepts, however, defy clean descriptions in words or rules. As Justice Potter Stewart famously remarked in his 1964 Supreme Court opinion about defining obscenity: “I know it when I see it.” While his comment was in the context of pornography, the principle applies broadly. Many phenomena—whether it’s recognizing a picnic scene, identifying a bird species, or detecting fraudulent activity—are easier to classify intuitively than to define explicitly.

Neural networks excel at this very problem. By training on large datasets of sensory input, they create sophisticated models that capture patterns we “know when we see them.” These models can then act as operational extensions of knowledge graphs, enabling reasoning systems to bridge the gap between human intuition and machine inference.

Consider a public ontology in the medical domain, such as one used to classify dermatological conditions. A condition like melanoma (skin cancer) has well-defined textual descriptions in terms of size, color irregularity, and asymmetry. However, the actual diagnosis often depends on visual recognition—a task inherently intuitive and difficult to codify.

Now imagine linking this ontology to a neural network trained on medical image datasets containing millions of skin lesion photographs. This neural network, tuned to identify melanoma and differentiate it from benign conditions, becomes an extension of the ontology. Here’s how the linkage could work:

- Ontology Node: “Melanoma” in the medical ontology.

- Neural Network Metadata: A trained model named

SkinLesionClassifierNN, with details about its training data and purpose. - Relationship: A property such as

ex:linkedToNNconnects “Melanoma” to the neural network. - Actionable Output: Medical practitioners could query the ontology for “early-stage melanoma” and receive not just semantic descriptions but also actionable tools—ex. upload a photo of a lesion and get a neural network’s probability-based diagnosis.

By combining the structured reasoning of an ontology with the perceptual expertise of a neural network, this integration provides a richer, more practical system.

In the Semantic Web ecosystem, the neural network can be treated as an entity within the graph:

- Neural Network Representation: A node with properties describing the model, such as input types, training dataset, and purpose.

- Linking Property: A standard or custom property (ex.

rdfs:seeAlso,ex:linkedToNN) to connect ontology concepts with neural networks.

This is how that might look as a turtle file:

@prefix ex: <http://example.org/ontology#> .

@prefix rdfs: <http://www.w3.org/2000/01/rdf-schema#> .

# Ontology concept

ex:Melanoma a ex:MedicalCondition ;

ex:linkedToNN ex:SkinLesionClassifierNN .

# Neural network metadata

ex:SkinLesionClassifierNN a ex:NeuralNetwork ;

ex:inputType "Image" ;

ex:purpose "Classify skin lesions as melanoma or benign" ;

ex:trainedOn ex:SkinImageDataset ;

rdfs:seeAlso <https://github.com/some_med_repository/skin-lesion-classifier> .

# Training dataset

ex:SkinImageDataset a ex:Dataset ;

ex:source "Dermatology Clinics" ;

ex:trainingExamples 500000 .Organizations that create public ontologies—whether in medicine, biology, or general knowledge—can transform their datasets into actionable, operational frameworks by linking them to neural networks. Imagine:

- A food ontology linked to neural networks that identify cuisines from images.

- An environmental ontology paired with models that analyze soundscapes for bird calls or environmental threats.

- A retail ontology connected to networks trained to detect trends in clothing styles from social media photos.

By doing so, these ontologies grow from being passive repositories of information and become dynamic tools that interact with real-world data.

Potter Stewart’s insight—”I know it when I see it”—is surprisingly relevant in this era of AI. For organizations that create ontologies, it’s a reminder that the world is full of concepts that resist easy definition but can still be identified with clarity. Linking these ontologies to neural networks trained on sensory inputs like images, video, and audio provides a bridge between semantic precision and intuitive perception.

The challenge, then, is to go beyond words. Enrich the Semantic Web with tools that “see,” “hear,” and “sense”—just like we do. The result is a smarter, more connected world where knowledge graphs truly become maps for navigating both structured and unstructured realities.

This blog is Chapter VI.2 of my virtual book, The Assemblage of Artificial Intelligence.

Notes

1. Importantly, each mini-column itself is made up of several layers, stacked vertically, each layer playing a distinct role in processing and communicating information. So to be more precise, it’s useful to think of a mini-column not as a single neural network, but as a stack of coordinated, interconnected neural networks, each layer with its own role and connectivity pattern. For example, Layer 4 could be seen as an input-focused network, processing raw sensory data—its dendrites tuned to feedforward input. Layers 2/3 behave like integration networks, reaching out laterally to other mini-columns, exchanging context, and building consensus. Layer 5 functions like an output network, sending signals (the axons) beyond the local region. Layer 6 serves as a feedback network, modulating the input layers based on higher-level expectations. Together, these layers aren’t a monolithic neural net but rather a tightly linked ecosystem of micro-networks—specialized, communicating vertically and laterally, adapting dynamically.

This layered assembly makes mini-columns more powerful and flexible than a flat network, embodying both hierarchy and distributed consensus. It’s this nuanced organization that lets the brain model complex systems with remarkable efficiency.

2. I want to clarify that I am not suggesting a one-to-one correspondence between mini-columns of the neocortex and specific objects. While this blog uses knowledge graph nodes to represent identifiable objects or concepts, the actual function of mini-columns is far more distributed and abstract. The use of discrete object nodes here serves as a simplified analogy, not a literal mapping of how the neocortex encodes information.

Notes

- This blog is Chapter VI.2 of my virtual book, The Assemblage of Artificial Intelligence.

- Time Molecules and Enterprise Intelligence are available on Amazon and Technics Publications. If you purchase either book (Time Molecules, Enterprise Intelligence) from the Technic Publication site, use the coupon code TP25 for a 25% discount off most items.