“Context engineering” is emerging as the evolutionary step over prompt engineering. It’s the deliberate design of everything an AI system can access before it produces an answer. The goal is to make it work on the right problem, with the right facts, under the right constraints. That is, by mitigating “context drift” as the AI iteratively refines a superior answer.

It goes far beyond skillful prompt engineering. It’s about orchestrating retrieval (the “R” in RAG), managing memory and state, connecting tools and workflows, and enforcing policy so the model becomes situationally aware of your enterprise—Slack threads, service tickets, BI dashboards, knowledge graphs, calendars, documents, and everything else that gives meaning to the work.

As models gain longer context windows and tighter integration with data and tools, the competitive question has shifted. It’s no longer Which model performs best? but What best controls and curates the context?

Here’s a definition I’ve cobbled together from three seemingly prominent sources, in an attempt to set a baseline of being in sync with the world:

- Harrison Chase and LangChain’s “The Rise of Context Engineering” (2024)

- Zep AI’s “What Is Context Engineering?” (2024)

- Mezmo’s “Context Engineering for Observability” (2024)

Context engineering is the practice of building adaptive systems that give an AI model the right information, tools, and constraints—in the right format and timing—so it can plausibly and safely perform its task. It spans data grounding (RAG across enterprise sources), memory and state management, agent coordination, policy enforcement (from access control to PII redaction), and the monitoring of quality, cost, and drift.

Note: The term context engineering is still very new, and its meaning will likely evolve. We don’t even have universally solid definitions for AGI, ASI, or arguably even AI itself.

Recent players in the AI space—especially from LangChain and related frameworks—converge on this view: prompt engineering operates inside the context window, while context engineering determines what fills that window and how it’s governed. Think of it less as copywriting and more as system and product design for AI behavior.

Where this meets enterprise data is that Google and others now explicitly frame embeddings, RAG, memory, and tool use as context-engineering primitives for connecting mail, documents, and line-of-business systems—exactly the Slack/email-centric use cases.

Keep in mind that my definition of context engineering in the context of this blog, which is in the context of my two books, may not match the definition I offered above. But I believe it is very close in spirit. Here are a couple of great articles and videos that capture the definition of different voices (I recommend the YouTube videos first as they are short and more enjoyable):

- Articles

- YouTube Videos

Context Engineering and My Two Books

When I first heard of context engineering a few weeks ago, I had initially set it aside as an “AI buzzword of the week” that I’d get to when I get to it. When I did get to it a couple of weeks ago, it seemed that the main idea of my two books can now be associated with a named concept.

My two books, Enterprise Intelligence and Time Molecules, are about providing AI with knowledge-level answers in a similar manner to how business intelligence (BI) has provided information-level answers to human BI consumers. That is, answers that are based on highly-curated data, are returned very quickly, and are presented in a user-friendly manner.

At the knowledge level of the DIKUW progression (data, information, knowledge, understanding, and wisdom), maintaining context requires more effort than at the information level of BI. Roughly speaking, the context of the information-level answers of BI is mostly the WHERE clause (filter, slice) of a SQL GROUP BY query. Obtaining knowledge-level answers for AI agents will often involve a complicated (perhaps even complex) system of tasks distributed among multiple AI agents and data sources. The context of the AI query is more of a challenge to maintain across a complicated or complex system.

While context engineering encompasses a wide range of practices—spanning memory management, tool orchestration, policy enforcement, and observability—this discussion focuses on one particular facet: retrieval and packing. It’s the art and science of selecting and assembling the right knowledge within a limited context window so that an AI agent can reason effectively. This is the “R” in RAG, the retrieval and grounding layer, where the agent determines what belongs in the window and how to compress it for maximum salience.

In that sense, my two books, Enterprise Intelligence and Time Molecules, provide the substrate that makes this form of context engineering possible. Enterprise Intelligence establishes the curated, governed foundation—knowledge that’s clean, relevant, and retrievable at high speed. Time Molecules adds the temporal and procedural layer, defining when and why certain information should flow between agents or steps. Together, they create a disciplined retrieval ecosystem that allows AI agents to compose lean, meaningful, and context-rich prompts from enterprise knowledge—packing just enough truth into each window to make the next reasoning step both efficient and correct.

This blog describes context engineering in relation to my two books and how each maps to what I see as the two primary pillars of context engineering. As it is with most software developers, we’ve experienced inventing a solution on our own, only later to learn that is now has a name. Context engineering is indeed a major aspect of the two books.

There is a list of blogs that provide background of my two books in Part 1 of my virtual book, The Assemblage of Artificial Intelligence (which is a third book that is my online curated collection from my many blogs—not formally published by Technics Publications like the other two).

For a minimal introduction to my three books (and the virtual book), please read:

- Enterprise Intelligence: Enterprise Intelligence, TL;DR—Fittingly for this blog, I append this to my LLM prompts when asking it for advice related to this book.

- Time Molecules: Sneak Peek at My New Book—Time Molecules or Time Molecules TL;DR

- The Assemblage of Artificial Intelligence: Introduction

A few notes:

- This blog is Chapter VI.5 of my virtual book, The Assemblage of Artificial Intelligence.

- Time Molecules and Enterprise Intelligence are available on Amazon and Technics Publications. If you purchase either book (Time Molecules, Enterprise Intelligence) from the Technic Publication site, use the coupon code TP25 for a 25% discount off most items.

- Important: Please read my intent regarding my work on AI and disclaimers.

Distributed Systems and the Need for Context Engineering

The conversation around context engineering really begins with the distribution of intelligence. We’re no longer dealing with one monolithic, all-knowing model but with ecosystems of specialized AI agents—each fine-tuned for its own domain and connected to its own resources. We can spin up domain experts, plug them into dedicated data sources or tools, and let them work in parallel.

This distributed model has major advantages:

- Task Parallelization: multiple agents can run subtasks simultaneously, speeding up complex workflows.

- Specialization: each agent can become an expert—fine-tuned or augmented with domain-specific embeddings, APIs, or databases—to deliver higher-quality results.

- Loose coupling: agents can be replaced or upgraded independently, letting us plug and play new capabilities without refactoring the whole system.

But distributed systems also introduce familiar trade-offs:

- Coordination overhead: managing who knows what, when, and how to hand it off.

- Inconsistent state: agents may operate on slightly different or outdated snapshots of reality.

- Communication costs: excessive data sharing can overload channels and inflate compute costs.

- Error propagation: bad context or missing provenance from one agent can cascade downstream.

These are the same challenges that led to decades of research in distributed computing — now re-emerging in the AI era. Context engineering is our new coordination fabric: the discipline that keeps distributed reasoning coherent, efficient, and safe. It ensures each agent receives only the context it needs at the moment it needs it, with clear provenance and rules of engagement.

AI Agent Scrum

“Over-communicate”. That’s been a slogan on many of the projects I’ve worked on. I understand and appreciate it. But, like any good rule, it can be taken too far. Over-communication has diminishing returns. What we actually need is minimal over-communication—to err on the side of caution, but only just enough.

That’s the role of the daily scrum meeting of the Agile project methodology. A cross-functional team—developers, analysts, stakeholders, business partners—gathers across the streams of the project. The goal is to synchronize, not to deliberate endlessly. The first guardrail against over-communication is time. Each participant gets their turn, one at a time. The project manager—part MC, part director, part judge — ensures that anything requiring more than a few seconds of discussion becomes a follow-up or side meeting.

Because even teams can’t truly listen in parallel, those turns matter. And yet, as each person speaks, something they say might trigger an insight in someone who already spoke—something they didn’t know they didn’t know. That’s the structured serendipity of scrum meetings.

Now let’s apply this principle to teams of AI agents. A set of AI agents working on a prompt or task are effectively a mini-project team. Each is an expert domain model—like a specialist in design, data, or compliance — working toward a shared deliverable. Each has its own inputs, assumptions, and partial understanding of the problem. Just as in human teams, their coordination matters as much as their individual intelligence.

AI agents already know how to communicate reactively—within a RAG process, they request additional context or data when needed. But what’s missing is proactive communication: the digital equivalent of a daily scrum. An AI Project Manager agent could convene these interactions, collecting progress updates and needs, and deciding what to prioritize or delegate next. Better yet, each expert agent could submit a prioritized list of needs—its equivalent of “what I need from others today.”

That simple structure would prevent the flood of irrelevant data that happens when every agent dumps everything “just in case.” It keeps the AI ecosystem minimally over-communicative—erring on the side of caution, but only just enough.

Two Pillars of Context Engineering

As soon as intelligence becomes distributed—many agents, many tools, many partial memories—the problem shifts from how smart each model is to how well they share context. That’s where context engineering steps in. It isn’t just about smarter prompts or longer context windows; it’s about building a coordination fabric that lets specialized agents reason together without flooding each other with irrelevant data.

In practice, context engineering rests on two major pillars. The first governs how agents pass context as they go, making sure every hand-off is frugal but sufficient—just the evidence, timestamps, and links the next step will truly need. The second ensures an enterprise-wide foundation of context, so those agents draw from clean, consistent, governed sources instead of scraping raw systems. Together, these pillars form the operational discipline that keeps distributed intelligence coherent, efficient, and auditable.

Pillar 1 — Context of a Case

The main value of context engineering is to ensure that an LLM prompt has sufficient context to resolve its task correctly. A context window is the span of tokens the model can “see” at once—the running bundle of text/JSON/tables you feed it (prompt + retrieved snippets + tool results). Anything outside that window is invisible to the model for the current step unless you re-supply it. Bigger windows let you pack in more, but they’re still finite and costly to fill.

The solution was originally to increase the context window along the “more must be better” paradigm. They encourage dumping whole threads and reports, which slows responses, raises cost, and blurs the model’s attention. But as it is for me (a person who does have an intellectual context window) when given an assignment, I can do a better job if my instructions are as succinct as it needs to be—not as succinct as it could possibly be nor a convoy of trucks full of documents.

Context engineering treats the window as scarce: at each step, the agent looks ahead to what the next step actually needs and passes a frugal, typed hand-off—just the few fields, timestamps, and links downstream will use, plus provenance. Maybe even a concise, elevator-pitch-worthy summary.

Markov Models and Non-Deterministic Finite Automata as Workflows

This is related to Time Molecules through process mining. (The subtitle of Time Molecules is: “The BI Side of Process Mining and Systems Thinking”.) Process mining tells you the real paths and hand-offs; this approach turns those paths into operational context policies. Each mined step declares its NEEDS/PROVIDES, so parallel lanes pass lean packets and the integrator assembles decisions quickly. You get tighter conformance (explicit hand-offs), earlier signals for prediction, and cleaner audits—moving process mining from after-the-fact analysis to in-the-flow guidance.

Markov models in the Time Molecules framework already describe how one event transitions to another over time, with probabilities reflecting observed behavior. When those transitions are transformed into non-deterministic finite automata (NFAs, or Petri Nets), each state can take on richer operational meaning. That is, not just the name of an event, but also metadata about what it requires, produces, and may encounter.

And while process mining in its traditional form often analyzes workflows that span days, weeks, or months, a team of AI agents can execute the same logic within seconds to minutes—compressing operational timelines and turning business processes into real-time systems. In doing so, they bring process mining into the temporal domain traditionally associated with non-deterministic finite automata (NFAs), which are often conceived as operating over ultra-fast transitions. AI agents essentially make human-scale processes run at NFA-scale speed, closing the gap between enterprise workflow and computational automata.

However, I’m not saying agentic AI workflows should be bound by an NFA structure. Rather, it’s usually a main AI agent engaging other AI agents as necessary. In a multi-agent solution, there isn’t a hard-coded routing of tasks as there would be in a traditional workflow engine. Yet it isn’t chaotic either. Each run of the agents produces various but bounded sequence of events—paths that process mining can study and summarize as a Markov model. From these observed paths, an NFA can then be derived, capable of representing all the plausible routes the agents might take. The result is a dynamic but analyzable system: one that learns its own structure over time while preserving the ability to track, audit, and optimize its routes.

Each “state” could therefore include a profile of:

- Inputs—Parameters or context fields expected from upstream agents. For NFAs, this is a list of transitions.

- Outputs—The results or data structures that will be passed forward. For NFAs, this is a list of what it fires to other states.

- Description—What the step does or represents within the process. What problem does it solve?

- Exceptions—The conditions under which it should branch or escalate. Describe how and why the exception occurs.

For inputs and outputs, unlike it would be for API or microservice function calls where a terse parameter name, data type, and range is of the most interest, for an AI agent it might be a textual description of the parameter. The text description conveys richer context about what that parameter represents, and the collection of these descriptions helps reveal the function of the state itself.

From these declared inputs and outputs, we can also infer dependencies between agents—what can start only after something else finishes. For example, a kitchen can’t begin preparing a meal without first receiving an order. These inferred dependencies become the backbone of the workflow, helping the system discover not just what happens, but in what order and why.

This NFA form turns the Markov chain from a statistical map into an operational contract between AI agents. When an upstream agent completes its task, it looks ahead to the next probable states—those with the highest transition probabilities—and assembles just the minimal context that those downstream states declare as needed. Instead of dumping everything into the prompt, the upstream agent passes a typed packet of context, shaped by the Time Molecule’s workflow model.

There are two complementary ways that Time Molecules enhance this first pillar of context engineering. The first is by converting Markov models into NFAs, giving structure (flexible, “non-deterministic” structure) and explicit context contracts between agents. The second is by using the Markov model as a predictive tool to anticipate the most likely sequence of upcoming steps. Instead of relying on complex calculations, the model looks at the current state and uses its understanding of likely transitions to predict what might happen next, and even a few steps beyond. This allows the main agent to prepare and shape the context it passes forward, not just for the immediate next step but for a few probable future steps. By doing so, the system can prefetch and tailor information, improving coherence and efficiency across the agent workflow.

In effect, context engineering becomes the runtime application of process mining: mined event paths define what each step needs and provides, and the AI agents use that structure to pass information efficiently and predictively. Over time, the system refines its transitions—its Time Molecules—based on observed outcomes, learning which contextual fields actually matter for success. This closes the loop between observation and orchestration: every transition becomes both a probabilistic expectation and a communication protocol.

Extending the AI Agent Scrum analogy, the NFA is like a kanban—each state corresponds to a “work item” or step in progress, moving from one lane to another as agents complete their tasks and pass along minimal context packets. The flow of these transitions, guided by probabilities and context contracts, keeps the system lean and synchronized—neither over-communicating nor starving the next agent of what it needs.

See my blog, Reptile Intelligence: An AI Summer for CEP, for a deeper dive on the progression of event processing, to Markov models, to NFA and/or Petri nets.

The short version of how I frame it:

- RAG is not “retrieve everything.” It’s step-wise selection and compression under budgets (tokens/bytes/latency).

- Context contracts. Each workflow state advertises NEEDS / PROVIDES / GUARDS so hand-offs are light but intentional.

- Time Molecules for foresight. Transition priors guide prefetch (“what the next state will probably need”) without blasting the window.

- Receipts, not vibes. Every assertion travels with provenance, confidence, and a link back—so downstream doesn’t re-infer.

Time Molecules—run-time context discipline, contracts, and Time Molecules-driven prefetch—in a follow-up. For this piece, I’ll offer a quick example.

The main idea is that at every node, the AI agent checks the downstream workflow metadata (the step’s declared NEEDS/PROVIDES/GUARDS). Using that “context contract,” it decides exactly what to submit downstream—and nothing more—so we keep the context window under control (tokens, latency, cost) while still handing off the critical facts and links the next step will rely on.

Example

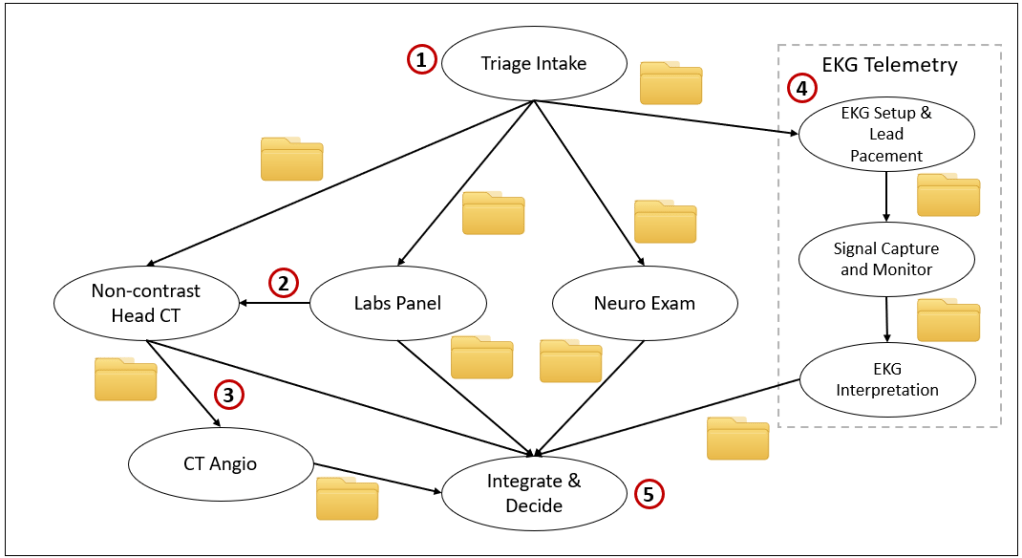

Figure 1 is an example of a case that can process in parallel. It’s a stroke (Cerebrovascular accident, CVA) workup with context hand-offs:

- Triage Intake fans out the case to four lanes—Neuro Exam, Non-contrast Head CT, Labs Panel, and EKG/Telemetry. Along with the orders, Triage emits the first little “folder” (a context packet): last-known-well time, current window, vitals, and a minimal patient token. That same packet seeds every lane so they’re working from the same clock and identifiers.

- Labs Panel runs in parallel and can push an immediate packet back to Head CT when values change the read—e.g., low glucose (stroke mimic) or abnormal platelets/INR (thrombolysis risk). That tiny folder is just enough: value + timestamp + why it matters.

- Head CT proceeds; if no hemorrhage and symptoms align, it opens the CT Angio branch to check for large-vessel occlusion. Imaging packets include a short finding, confidence, and a link back to the series—not the raw pixels.

- EKG/Telemetry shows three steps in the workflow. It’s possible the three steps are performed by three different people (or robot). Usually, the first two steps are performed by the same person, but the interpretation is by a doctor as well as an AI.

- Integrate & Decide is the join point. It assembles just the packets it asked for—CT/CTA results, labs that gate treatment, NIHSS, and rhythm—and renders the decision sheet: thrombolysis eligibility, thrombectomy candidate (if LVO), contraindications, and links to source evidence. Because each step passed forward the few details downstream needs, the final decision comes together quickly, with provenance, instead of a scramble through full reports.

The yellow folders sprinkled along the arrows are the point: tiny, deliberate context hand-offs that keep parallel paths coordinated and the integrator fast—and that’s Pillar 1 in action.

Pillar 2 — Integrated Enterprise-Wide Context

An integrated enterprise-wide awareness is what my book, Enterprise Intelligence, is about. That book describes the integration of the technologies that result in the ability to create not just a data source, but a comprehensive database required for intelligence. The blog, Enterprise Intelligence: Integrating BI, Data Mesh, Knowledge Graphs, Knowledge Workers, and LLMs, describes this.

It provides AI agents with a clean, governed, fast way to pull the right facts from across the enterprise—without spelunking through raw systems, for each query, from scratch.

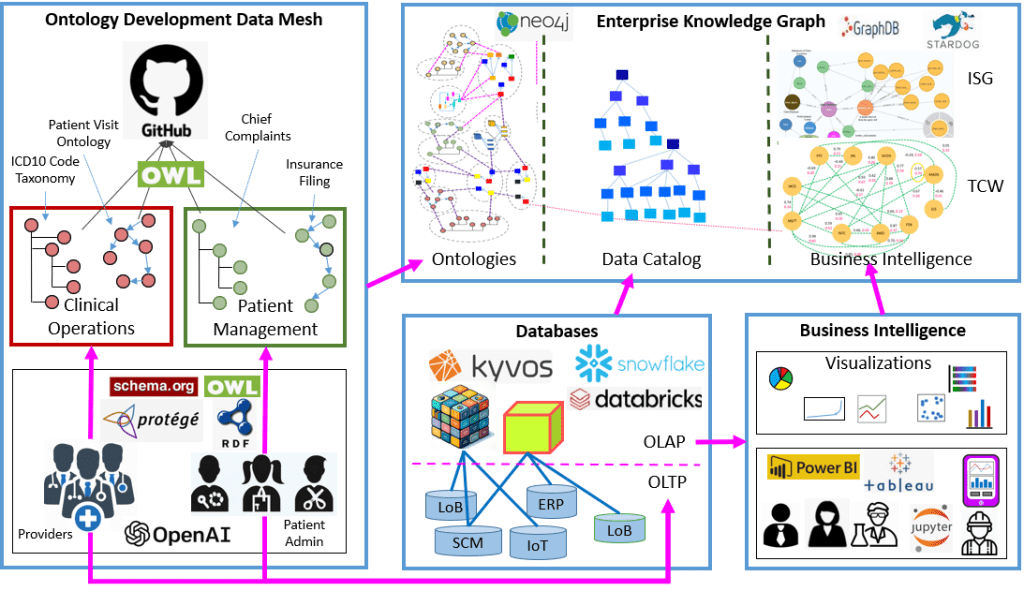

Figure 2 depicts how ontology-driven development, data mesh principles, and business intelligence converge into an Enterprise Knowledge Graph (EKG) that acts as the “brain” of the enterprise.

On the left, the Ontology Development “Data Mesh” shows how domain teams define their data semantics using shared standards. Ontologies such as Clinical Operations and Patient Management are authored in Turtle (TTL) syntax and encoded in OWL (Web Ontology Language), ensuring each domain’s knowledge—like ICD10 taxonomies, patient visits, or insurance filings—is formally represented. Tools like Protégé, schema.org, and RDF provide the scaffolding for defining classes and relationships, while GitHub manages version control and collaboration across contributors. The inclusion of OpenAI hints at AI-assisted ontology creation and validation.

These ontologies feed into the central Enterprise Knowledge Graph (EKG)—a structure combining three primary structures: Ontologies, a Data Catalog, and Business Intelligence. The ontology layer connects concepts defined by each data product team, forming a rich semantic web across domains. The Data Catalog organizes enterprise data hierarchically—from systems and databases (OLTP/OLAP) down to tables, dimensions, and attributes—making all assets discoverable and interoperable.

Below, the Databases box bridges operational and analytical systems. Platforms like Kyvos, Snowflake, and Databricks handle OLAP workloads derived from OLTP databases, feeding the catalog and supplying data to BI tools.

To the right, Business Intelligence transforms curated data into insights. Analysts and knowledge workers use Power BI, Tableau, and Jupyter to visualize trends and create insights that flow back into the EKG through two specialized layers: the Insight Space Graph (ISG), which captures BI-derived findings as reusable insight nodes, and the Tuple Correlation Web (TCW), which maps relationships among data tuples through correlations and probabilities. Notes: More on how data mesh (and data vault) facilitate the feasible onboarding of data from even the farthest reaches of an enterprise.

Together, these flows form a closed intelligence loop:

- Ontologies supply semantics.

- The Data Catalog provides structure.

- Databases and BI deliver evidence and interpretation.

- The EKG unites them all into a continuously learning and reasoning system.

The EKG serves as the primary source of information-level answers to AI agent queries—it’s the layer where context becomes computable, connecting raw data to curated meaning. This makes it not just a knowledge repository but the operational backbone of enterprise reasoning.

The result is a living, ontology-backed data ecosystem where human and AI agents can query, correlate, and reason across the enterprise with shared understanding.

For a short (5-minute read) overview the relevant parts, please first read: Charting The Insight Space of Enterprise Data. This is an overview:

- EKG (Enterprise Knowledge Graph). Typed entities, relationships, and events make retrieval semantic (“orders by affected customer in the outage window”) rather than brittle keyword search. BI is the spearhead, but the EKG is the context spine linking domains. It holds soft-coded logic—knowledge that can evolve—so agents reason across meaning rather than syntax.

- TCW (Tuple Correlation Web). Correlates tuples (qualified business facts) across time to rank relatedness—so the agent fetches the most likely relevant context first (top-k paths) instead of wandering a graph. Time becomes the universal join. Almost every signal carries a timestamp, allowing Slack, email, tickets, logs, and BI facts to align on a common clock. This makes cross-domain joins safe, repeatable, and measurable.

- ISG (Insight Space Graph). Captures compact “insight atoms” emitted from BI—anomaly cards, breakouts, cohort lifts—each with provenance. These are small, high-signal shards perfect for a context window and for sharing analyst discoveries enterprise-wide. They transform BI outputs into context-aware intelligence nodes that downstream agents can reuse.

- Pre-agg OLAP / Semantic Layer. Provides millisecond access to governed measures (“SLA breaches last 90 min by region”), returning tiny, typed tables instead of fact swamps. Governed, pre-aggregated cubes ensure both speed and precision—crucial when context windows are scarce and every token must count.

- Putting It All Together. Start with curated BI, capture salient insights (ISG), connect them over time (TCW), and bind everything with a semantic backbone (EKG). The result is an enterprise-wide context space where AI agents and humans alike can retrieve precise, provenance-rich information instantly.

Business Intelligence for AI Agents

Enterprise Intelligence builds upon a solid BI foundation. This book’s central idea is build enterprise intelligence on top of a solid BI foundation.

BI systems have spent decades refining exactly what LLMs and AI agents now need most—curated, governed, easy to understand (user-friendly), high-speed context. Although LLMs can navigate its way through cryptic attribute names tossed into complicated schemas, the dimensional model of most BI data sources relieves some of that intellectual burden for LLMs as well as human BI consumers.

It’s the product of years of selective extraction, cleansing, validation, and dimensional modeling—optimized to answer questions fast. Long before RAG existed, BI solved the same latency and relevance problems: users asked open-ended questions, and the system had to return precise answers from complex data in milliseconds. BI was the original retrieval layer.

That’s why, for AI agents, a BI foundation is critical. RAG queries must be fast and composable. When dozens of agents ask contextually different questions—slicing and dicing by region, timeframe, or customer—BI systems already know how to respond. They’ve been doing it for decades.

A key enabler of this speed is pre-aggregated OLAP, where measures are computed and stored ahead of time so every query returns in milliseconds. This pre-aggregation pattern, championed by platforms like Kyvos, gives enterprises instant, governed access to complex analytics across billions of rows—precisely what distributed AI agents require. In the AI era, the same pre-aggregations that power dashboards now power context windows. See:

- The Ghost of OLAP Aggregations – Part 1 – Pre-Aggregation

- The Ghost of OLAP Aggregations – Part 2 – Aggregation Manager

Kyvos’ MCP Server in the RAG Aspect of Context Engineering

In the world of RAG pipelines, one of the key challenges is anchoring generative models to governed, high-performance enterprise semantics—rather than feeding them raw blobs of text or loosely defined data. The Kyvos MCP Server plays precisely this role: as a standards-based endpoint (via the Model Context Protocol) it enables an LLM or agent to query the Kyvos semantic layer (measures, dimensions, filters, valid grains) as if it were a trusted “context source”.

In effect, it turns Kyvos from “just another data source” into a context-engineered RAG source— the model asks “which semantic object” and receives precise, governed context, then uses that for retrieval or generation. Because the server enforces governance, business definitions and scale, the RAG loop becomes far more robust: the context is high-value, known, and aligned with the TCW and Strategy Map rather than ad-hoc dumps.

In other words, rather than treating “Kyvos as a source” as simply a content store, it’s treated as a context manager for agents—and the MCP server is the access gate that ensures the right context, at the right grain, to the right model. This results in fewer hallucinations, more semantic alignment, clearer provenance and a context architecture that supports your larger story of engineering context, not just managing data.

Faster Onboarding of BI Data Sources

One of the major reasons that BI hasn’t historically scaled from just the few major data sources to the hundreds of data sources that exist in all larger enterprises is the painstaking mapping between systems. Every column, key, and hierarchy has been manually reconciled by BI developers—a task as critical as it is grueling. In fact, the application of AI I’ve spent the most time on is Master Data Management (MDM), matching objects across enterprise domains.

Today, LLMs and semantic modeling help automate that burden by discovering relationships, synonyms, and lineage. Meanwhile, Data Mesh and Data Vault architectures provide the one-two punch for accelerating data onboarding—combining autonomy with consistency so new sources plug into the BI ecosystem more easily.

BI should be the semantic and performance substrate for distributed AI systems. It provides governed, time-aligned, query-optimized data that lets AI agents focus on reasoning, not rummaging. Context engineering simply extends that discipline into the AI era: instead of dashboards and cubes, the consumers are LLMs and autonomous agents—but the principles of clean modeling, fast retrieval, and curated trust remain exactly the same.

Conclusion

Pillar 1 (Time Molecules) and Pillar 2 (Enterprise Intelligence) are how I currently interpret the meaning of context engineering. The term, context engineering, is quite new and so I expect that my interpretation and the generally accepted interpretation will drift over time. But by whatever name, the goal of my three books is a that intelligence is a distributed system of heterogenous agents and data. They require Bayesian-like communication (new information to keep the assumptions up to date).

As I hinted at earlier in the topic, AI Agent Scrum, the way BI worked with the ecosystem of decision makers (BI platform, BI consumers, managers/executives, subject-matter experts) applies to the ecosystem of AI decision making (BI information, human knowledge workers, multiple modes of data, information, and knowledge, and AI agents). With that in mind, around the late 2000s, a hip saying around the BI world was:

BI is about providing the right data at the right time to the right people so that they can take the right decisions. – Nic Smith

In that light, context engineering isn’t just a design discipline but a philosophy of coordination—ensuring every agent, model, and data source contributes to a shared understanding without overwhelming the system. It’s the connective tissue between autonomy and coherence, where Time Molecules define how information flows moment to moment, and Enterprise Intelligence defines the semantic landscape it flows through. Whether we call it context engineering or something else in the future, the essence remains: intelligence emerges from communication that is timely, selective, and grounded in shared context.

An excellent video explaining context graphs, Context Graphs: AI’s Next Big Idea from AI Daily Brief

That video is based on a recent article, AI’s trillion-dollar opportunity: Context graphs – Foundation Capital, Jaya Gupta, Ashu Garg.