Abstract

Complex Event Processing (CEP) has long been dismissed as mere real-time infrastructure, yet it embodies the scalable, deterministic substrate that artificial intelligence has overlooked: a high-performance System 1 layer as described in Daniel Kahneman’s Thinking, Fast and Slow. System 1—fast, automatic, intuitive, massively parallel, and effortless—handles the overwhelming flood of sensory (or in enterprise terms, event) data to deliver immediate situational awareness before slower, deliberative System 2 processes engage. In AI architectures, this is the missing “reptile intelligence”, more sophisticated than primitive reflexes (worm-level one-shot rules), yet grounded, reflexive, and non-abstract, akin to the limbic/subcortical circuitry that enables reptiles to recognize complex patterns in survival-critical environments through dense, parallel triggers.

Using Non-deterministic Finite Automata (NFAs) compiled from heterogeneous sources—PMML machine-learning models, RDF/Semantic Web triples, Prolog logic, and even LLM-generated rules—CEP engines like Apache Flink can evaluate thousands to millions of patterns concurrently over high-velocity streams. Broadcast events advance every recognizer in lockstep, producing higher-order signals that feed upward into reasoning layers (Prolog-style deduction, LLM analogy/planning) without central bottlenecks. This creates true neuroplasticity at scale: dynamic rule injection, versioning, historical state time-travel, and feedback loops that evolve the system’s “senses”.

Despite prototypes dating back to SSAS data mining (1998–), the Micron Automata Processor vision (2013), and my own software-based Reps NFA implementations (handling 200,000 rules on commodity hardware), CEP never received its “AI summer”—overshadowed by Big Data, deep learning, and generative models that dominated narratives. Yet as LLM limitations in grounding and real-time awareness become clear, the industrial maturity of Flink (proven at Alibaba/Uber/Netflix scale) positions reptile intelligence as a first-class component in the Assemblage of AI, the fast-thinking foundation that turns raw event torrents into coherent, actionable cognition for enterprise-grade intelligence.

A lot has happened since the Automata Processor in the mid 2010s and Flink over the past few years. The moment for CEP is now—not as plumbing, but as the essential System 1 connective fabric enabling thousands of models and rules to collaborate in real time.

Complex Event Processing

AI doesn’t emerge from a hodgepodge of single-function models—a decision tree that predicts churn, or a neural net that classifies an image, which only see one quality of the world. The AGI-level intelligence that’s being frantically chased requires massive, organized integration of learned rules. That is, a large, heterogenous number of composed rules and workflows into recognizers from which we are able to draw a level of situational awareness, mitigate blind spots, and approximate the “theory of mind” and motivations of the objects that are observed.

Large Language Models (LLM) demonstrate this principle in the text world. They integrate written text across millions of authors and thousands of domains into a single substrate, letting patterns and meanings emerge that no single document or model could capture. Data science derived rules and workflows need the same treatment. That’s what Complex Event Processing (CEP) has always been about. It’s not about a focus on one model at a time, but a substrate where many recognizers run in parallel and their outputs combine into the full story of what is happening.

Complex Event Processing (CEP) is about integration—rules, workflows, recognitions—running together to lift raw torrents of events into higher-order signals. Microsoft’s SQL Server Stream Insight in 2008 was one of the first enterprise attempts. It was a legitimate AI product, but it never had its “AI summer.” Instead, it was overshadowed by shinier movements that Gartner and the press pushed to the top of concern lists:

| Years (approx.) | “Big Thing” in AI/Data | Overshadowing CEP | CEP’s place in the Shadows |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2008–2010 | SOA / ESB, early complex-event ideas | Architectural buzz dominated | StreamInsight announced/early; niche awareness |

| 2009–2012 | Big Data (Hadoop/MapReduce), NoSQL | Top of hype; new stacks everywhere | CEP sidelined; pilots in finance/telco |

| 2011–2014 | In-memory DBs (HANA), real-time BI; Data Science goes mainstream | “Data scientist” era; Python/R ascendant | CEP present but quiet; StreamInsight fades |

| 2012–2016 | Deep Learning boom (post-AlexNet → industry) | DL soaks up mindshare + GPUs | ASA GA; CEP seen as windowed SQL/ETL-ish |

| 2016–2019 | Streaming platforms (Kafka), Flink/Spark Streaming mature | Stream-first architectures | CEP = cloud feature; Flink/CEP grows in OSS |

| 2019–2021 | MLOps / Model ops | Tooling focus, pipelines | CEP steady as plumbing; used but not headlined |

| 2022–2023 | LLM shock (ChatGPT, instruction-tuning) | All attention on GenAI | CEP invisible to exec narratives |

| 2024–> | GenAI productization, multi-modal | GenAI everywhere | CEP under the hood; ready to re-emerge with “massive rule integration” |

Stream Insight evolved into its cloud form, Azure Stream Analytics (ASA). Many might only be familiar with it as those WINDOW functions (tumbling, hopping, sliding, session). It’s a sidenote fixture in Azure data-centric certifications. Yet CEP’s essence—integrating recognizers and workflows into new events—is central to intelligence itself.

I see CEP as limbic-like: fast, deterministic, and complicated, but not abstractly complex. The world itself is complex, but the limbic system works more like a dense circuit of triggers than an open-ended simulator. CEP at scale—very large number of simple to complicated rules and highly iterative—is like reptile intelligence. The sort of cold-blooded, but still complex intelligence we observe in lizards, snakes, and alligators. It may sound like a step backwards in the quest for Artificial General Intelligence (AGI) by the AI powers that be, but it’s still a distinct component of our human-level sapient intelligence—obviously oversimplified, the limbic system, that “old” part of our brain.

CEP is a major part of the Assemblage of AI, not in the background in a forgotten corner or something superseded, but as a core system component.

LLMs vs. CEP

The star of today’s AI summer, LLMs, aren’t really the neocortex counterpart to CEP as the limbic system—though there is some overlap. The neocortex learns from a fairly clean slate (think of a brand new computer with just the OS and nothing else), on the job, bottom-up, through direct interaction with the environment, reinforced by feedback from parents, teachers, and consequences. LLMs learn more like a student who has read every book in the library. They absorb the accumulated record of what people have already figured out, encoded in text, then recoded into synapses.

That makes LLMs less like a raw learner and more like a translator of knowledge—albeit incredibly versatile. They translate between forms of knowledge. They map metaphors to equations, specialist jargon to plain speech, or natural language to code. They can bridge between experts and those at any other level, between domains that don’t normally intersect.

When LLMs “hallucinate”, it’s really a kind of “imaginative translation”—guessing at a bridge where no explicit one exists, just like all creative people. Nothing stands out with strong statistical backing, so it creates a hodgepodge out of a big bag of minor facts. In many ways, I actually like that this happens, as opposed to how they are sometimes an opinionated brick wall.

The neocortex, on the other hand, is more of a vast mesh of small, narrow-scoped, highly linked neural networks—cortical columns. Each cortical column is tuned to various permutations of sensory input. Millions of them richly interconnect—in what is a truly complex way—feeding forward and back, constantly recognizing things, forming stories of what’s happening, and refining our understanding. It’s an engine for grounded abstraction, built from the bottom up out of lived perception.

This is the comparison I’m making. LLMs and the neocortex are analogous in that they are extremely versatile structures that self-organize through a process exposed to massive a volume of information. For LLMs the information is already formed and for the neocortex, it’s fed over time. For CEP versus the limbic system, it’s painstakingly organized through a process of trial and error, the former with the process of machine learning and the latter, evolution.

Table 2 summarizes this:

| Component | How it learns | Character | Strength | Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LLMs (AI, Learned) | Trained on massive amounts of recorded human text — book learning at scale | Translator of knowledge, versatile self-organizer | Bridges domains; maps metaphors to equations, natural language to code | No grounding in lived experience; imaginative but sometimes hallucinatory |

| Neocortex (bio, learned) | Learns on the job through sensory input and feedback; bottom-up | Mesh of many mini, narrow neural nets (cortical columns) | Grounded abstraction; builds complex models of the world | Slow to train; dependent on quality of teaching and intensity of lived experience |

| CEP (AI, engineered) | Painstaking data-science trial and error — rule-writing, NFAs, iterative tuning | Deterministic recognizer; reflex-like | Fast, reliable pattern detection; scalable on streams | Brittle if rules are wrong; tedious to evolve |

| Limbic System (bio, engineered) | Evolved through millions of years of biological trial and error | Complicated circuitry; survival reflexes | Immediate, robust responses to critical cues | Not versatile; not abstract reasoning |

Like the other components that have enjoyed AI summers (expert systems, semantic web, machine learning, deep learning, and now LLMs), CEP doesn’t supersede any of them. It’s a component that has its place in a full-scale AGI. As I mention in Assemblage of AI, the neocortex is the latest part of the human brain, but it didn’t supersede the functionality of the older parts.

Let’s start with two analogies (certainly not a biological claim) to get an idea of two levels of CEP.

Worm Intelligence

CEP implemented in Stream Insight, even ASA, is akin to worm intelligence. Where ASA is good enough for shallow reflexes required by worms, our human intelligence (and the AGI we seem to want so much) requires much more.

Strictly speaking, all events are complex because they’re born out of our world, which is itself complex. But the implementation of CEP in SQL Server Stream Insight and its direct descendent, ASA, doesn’t even rise to the complexity of worm intelligence. That’s understandable: the priority has been to handle floods of millions of events per second. Most intelligence reduces the complexity of the world into something merely complicated. The rules most essential for survival are strengthened and preserved.

It may get many things wrong, but it’s good enough so that some percentage of worms avoid those fat-tail (rare, sometime one-off) situations that would otherwise kill them. Long enough to reproduce, long enough to pass their DNA forward. Many, even most, individuals won’t make it that far, but that’s acceptable when what truly survives is the species.

That’s not good enough for sentient beings. Each of us is a species of one. With self-awareness, survival becomes a personal imperative. Reducing the fat tail of lethal situations requires scaling out: expanding the number of rules we can process, the number of things we can identify, and—most critically—the ability to adjust the rules as we learn.

ASA is good enough for worm-level reflexes, but its limits are clear:

- Simple, one-shot rules, usually sequential, often expressed as regular expressions or Boolean logic (roughly the scope of power of normal SQL WHERE clauses).

- Short-lived time windows, usually seconds or minutes—while real transactions can stretch into hours or days.

- Few in number: ASA buckles beyond 50–60 rules, whereas human-level intelligence requires millions to billions (what I’ve elsewhere called thousands of senses link).

So yes, CEP in its ASA form is “worm intelligence”—fast, reflexive, survival-oriented. But true intelligence, the kind AGI aspires to, requires scale, plasticity, and memory. That’s why CEP deserves a seat in the Assemblage of AI. Like expert systems, semantic web, machine learning, deep learning, and now LLMs, CEP doesn’t supersede other approaches; it complements them. Just as the human neocortex didn’t replace the older parts of our brain but built on top of them, CEP must be recognized as a core layer in the hierarchy of intelligence.

It’s important to understand that worm intelligence doesn’t recognize “things”. It reacts to signals, which are generally on some sort of scale of minimums, maximums, and thresholds.

Nonetheless, this worm intelligence level of CEP has its place. After all worms are extremely valuable to our survival, a major link, the garbage man of the food cycle, the link that starts it over. Remember, CEP is about extracting higher level insights from streams of events. That higher insight is usually an “event” as well (like the event of three spikes within a minute).

Reptile Intelligence

The focus of this blog is at the level of reptile intelligence—greater than worm intelligence but less than human (or even mammalian) intelligence. Reptile intelligence recognizes things very robustly with a highly complicated, integrated tree of rules. These highly complicated rules are trained into reptiles through their limited set of capabilities. In life, they become immersed into the complex environmental conditions in which they evolved and where they will interact with its prey and predators that are generally cleverer than the ones encountered by worms. For many, if not most, they will see “Game Over” before they can reproduce. It will be worse for those unfortunately immersed into environmental conditions different from the one they evolved in.

Worm-level intelligence still plays a part in reptilian intelligence. For example, the V1 that translates simple photons into shapes or pressure on our skin that translates to contact at some point of a body. Similarly, reptile intelligence plays a part in our sapient human intelligence. Our sapient intelligence doesn’t supersede reptile intelligence any more than reptile intelligence superseded worm intelligence. They are components of a system of intelligence I’ve been calling the Assemblage of AI. That is, the components that are assembled into a critically thinking, creative, and imaginative AGI.

In this discussion of worm and reptile intelligence, I’d like to point out that Complex Event Processing might be a bit of a misnomer. The world in which worms and reptiles live is mind-bogglingly complex, but not their intelligence. Worms pretty much live independently, worried about a finite set of easily recognizable things. That’s a life of simple rules of Boolean logic. For reptiles, their intelligence is very much more complicated, but still not complex—highly sophisticated complicated intelligence that does very well applied in a complex world.

Reptiles don’t think deeply like we do—meaning analyzing several steps ahead to test what might happen against goals. Where might the gotchas be? A reptile’s margins for error are in thick hides, strong jaws, and sharp teeth. our human margins for error are mitigated away in planning, with at least a plan b to pivot to at the drop of a hat.

My Continued Interest in CEP

As a BI developer/architect/consultant since 1998, integration of information has always been my top concern. Until a few years ago, I was mostly known for my expertise with SQL Server Analysis Services (SSAS, the “Multi-Dimensional” version), which is (arguably) about query performance. That meant I was often called in to solve performance issues. So it surprised some when I would say that integration of information was far more important than query speed. A “thoughtful” answer is more valuable than a fast one.

During the 2000s, I was also evangelizing the data mining capabilities in SSAS. These were early but powerful features—decision trees, clustering, association rules, naïve Bayes—long before Harvard Business Review declared in 2012 that “data scientist” was the sexiest job of the 21st century. What struck me while talking with departments across enterprises was the inevitability that there would be much more than a handful of models—there would be hundreds or thousands scattered across the enterprise, each focused on different signals and motivated by different outcomes.

That recognition led me toward CEP. Because intelligence isn’t a single-model act. When we recognize a person, it’s never just their face. A single recognition sparks thousands of associative rules: what issues are unresolved, whether they’re out of place, what it could mean, which topics to avoid, which to raise, the great or horrible memories tied to them. One recognition sets off a parallel cascade of reactions across countless neuron paths.

Over the years, I’ve taken several attempts to implement the integration of massive numbers of rules and models into a common substrate that can fire in parallel, not sequentially. That requires rules to be readily updatable—what I see as machine neuroplasticity. And sometimes the older rules must be retained, even when superseded, because they preserve the context of how a decision was made at the time. That becomes a kind of machine learning time travel—similar to how I described Prolog Time Travel—giving us a historical map of the models and rules that shaped each decision.

In terms of AGI, its relevance is more than just about high performance. It’s about integration at scale—the ability to compose, update, and preserve models in parallel—so that a system can recognize not just one slice of reality, but the full story.

The notion of developing such a system is a terribly massive undertaking—especially back then. So, I let it go, focusing on adding data mining to the typical BI deployment and eventually developing Map Rock in 2011 … until that ChatGPT thing rudely disrupted everything.

The Automata Processor

In late 2013, after Microsoft’s StreamInsight faded well off the radar, my interest in CEP resurged with Micron’s Automata Processor. It was a hardware implementation of NFAs for streaming recognition—massive numbers of NFA processors etched onto a chip. Since Micron is headquartered in Boise and I lived in Boise, I was able to contact them and explore how to use the automata processor for the application I just discussed.

Non-deterministic Finite Automata (NFAs) might sound like gratuitously esoteric computer-science mumbo-jumbo, but they’re actually a foundational idea from the same branch of computation theory that gave us regular expressions (RegEx familiar to most programmers) and, at the far end of the spectrum, the Universal Turing Machine (UTM) that underlies all modern computers. If a Turing machine is the heavyweight champion—able to simulate any digital computation—an NFA is a featherweight, stripped down, efficient, and focused purely on recognizing patterns in sequences of symbols.

What makes NFAs special is their simplicity. They don’t carry heavy memory or general-purpose logic. Instead, they move through a set of possible states in response to incoming symbols (letters, numbers, events). Because they can track many possible paths at once, they’re naturally parallel.

That simplicity is why NFAs lend themselves to hardware acceleration. In the same way that GPUs are built from vast grids of small, specialized compute units (reduced versions of the universal machine, optimized for vector math), Micron’s Automata Processor implemented vast grids of NFAs. Each NFA acted like a little pattern detector, and when you tiled thousands together you had a massively parallel recognition engine.

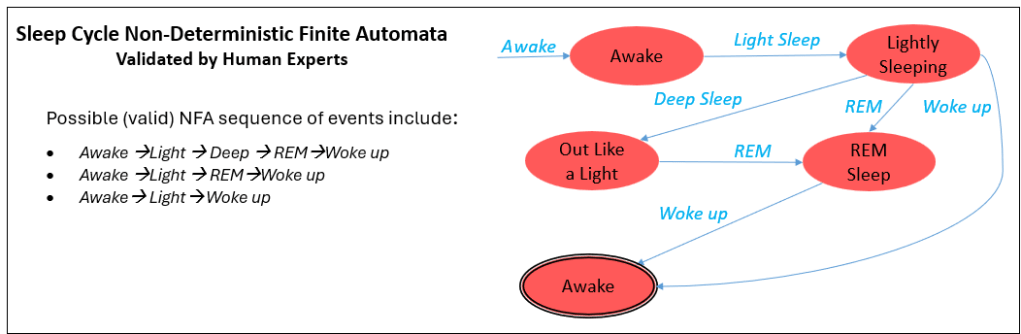

The NFA was loaded onto the Automata Processor using an XML-based encoding called ANML (Automata Network Markup Language). For an example of an ANML file, please see rem_demo, the ANML for an NFA of sleep cycles.

The crux of the insight is that if we can translate rules into a common encoding—NFAs—we can broadcast event streams to all of them at once. Every rule listens in parallel, each advancing or firing as the stream flows by. Instead of running one model at a time, you get thousands, even tens of thousands, running side by side, all in real time.

The idea was to convert ML models from all over the enterprise from PMML to NFAs and load them all onto the Automata Processor. This was meant to be a BI application that we called the APBIA (Automata Processor BI Appliance).

Figure 1 illustrates the central idea. Back then, data science was on a hockey-stick rise and ensembles were becoming the norm—predictive power came not from one regression or tree but from many models working together. Reps (which we’ll discuss soon) took that logic to its natural conclusion: not dozens, but thousands or tens of thousands of models, each compiled into NFAs and run in parallel against streams. Events flow into a symbol queue, then broadcast simultaneously to all NFAs—each symbol processed by all rules at once, not one at a time. Fired recognitions feed back into the stream as higher-level events. This was the heart of the design: an integrated processor of models, a substrate for recognition at scale.

But funny thing. The BI customer I brought told me his bosses were concerned with a whacky idea built on this really whacky hardware no one has ever implemented. Go figure … hahaha.

Additionally, much attention swung to alternative silicon for AI. A few threads pulled mindshare away from automata-based designs:

- FPGAs: reconfigurable logic you can tailor to streaming pipelines, low-latency inference, or even custom automata. They made it practical to “hard-wire” parts of a data path without committing to a fixed ASIC.

- Neuromorphic (“neuron-based”) chips: devices inspired by spiking neurons and synapses. IBM’s TrueNorth (2014) was an early, high-profile example; other programs explored large spiking fabrics and event-driven computation. The pitch was brain-like efficiency: massive parallelism, tiny power budgets, and temporal coding.

- GPUs: the decisive force. General enough to run everything, but especially good at deep learning’s dense linear algebra. Frameworks matured, hardware scaled quickly, and the ecosystem (CUDA, cuDNN, TensorRT) turned GPUs into the default AI substrate.

In that climate, the Automata Processor path lost momentum. Not because the idea of compiling rules to NFAs was wrong, but because market gravity favored platforms that could do many things well (GPUs), or be flexibly retargeted (FPGAs), or promised a radically different power/performance envelope (neuromorphic). My collaboration with Micron fizzled. But I still believed the NFA route had its own superior merits.

Reps

I pivoted a bit to working on a purely software implementation of the APBIA. I spent the next few years experimenting, building three generations of software implementations I called Reps—named after a pioneer of Zen in the West, Paul Reps, that my wife’s family knew back in the 1960s, not short for reptile. But I also realized as I wrote this blog that Reps could also be said to put the rep in reptile.

Reps was not about simply warehousing models in a registry (the ML model version of a data catalog). It was about integrating thousands of ML models, rules, and motifs into a single NFA-based runtime, all-consuming the same event torrent in parallel. Just as LLMs integrate knowledge across authors and domains into a common language, Reps integrates ML models into the common language of nondeterministic finite automata into an integrated structure.

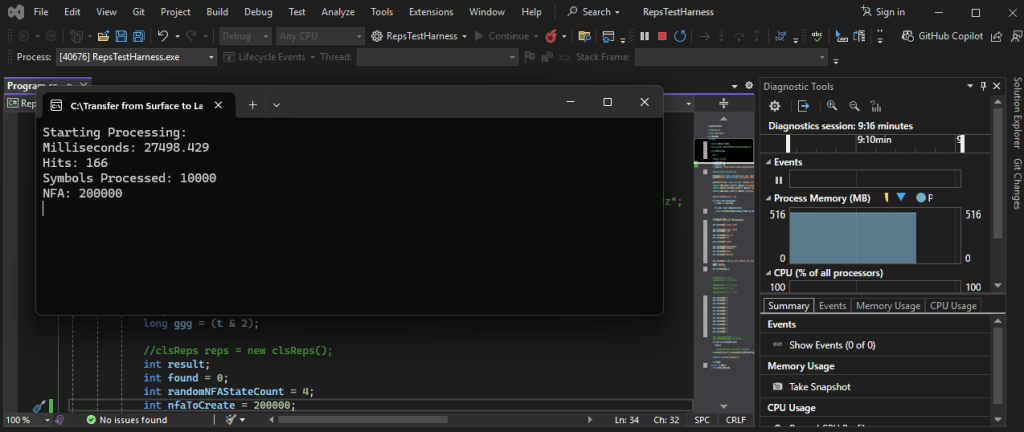

Reps is written in C#. I wrote three versions from around (2014 through 2017), each mostly from scratch. Although I wrote it as cleanly as possible, there are modules that can be optimized in C. I never did reach that point.

Just for kicks, I opened recently dusted off Reps Version 3.0 on my current main laptop—HP Pavilion Plus, 16 GB RAM, 8 core, 16 logical processors. It could process 10,000 symbols across 200,000 rules in about 30 seconds. That’s not scorching, but it’s enough for me to continue my development at minimal time and cost—if that’s what I want to do.

On a middle-of-the-road commodity server in an Azure cluster—say a D-series VM with 32 vCPUs, 128 GB RAM—the throughput of Reps was about 5–10× higher than what I observed on my HP Pavilion laptop. I simply provisioned the server on Azure, loaded the Reps exe, ran it, and deleted the server.

This isn’t GPU-scale acceleration or what the Automata Processor would have achieved, but for an NFA-based, event-driven runtime, the gain is exactly in the sweet spot of being horizontally scalable, affordable, and well within the reach of standard Azure commodity hardware. It means Reps can deliver CEP-style recognition speed at cloud scale while leaving the heavier lifting—deductive reasoning, correlation webs, and generative synthesis—to their specialized layers.

Rules are serialized into files in the RDF format of the Semantic Web world. This makes a lot of sense since NFA are directed graphs as are knowledge graphs. Additionally, with RDF, I could encode special attributes and other properties of states and events. A great example are “sameAs” synonyms. The Reps API (C#) is used to load one or more instances of Reps running on one or more servers in a cluster.

Meanwhile, unknown to me at the time I was actively developing Reps, Apache Flink was rising in open source, paired with Kafka, essentially becoming the thing I was aiming for without me knowing it. By 2017, Flink had traction and so I pivoted back to my bread-and-butter stack of BI, Azure, and ML. Seeing the traction of Flink was both inspiring and heartbreaking. It was inspiring in that CEP is a legitimate AI discipline. It never got its AI Summer, but in the spirit of the Assemblage of AI, it deserves recognition as the connective fabric that binds rules, workflows, and recognizers into living processes.

Flink

Apache Flink is the open-source engine that made Complex Event Processing (CEP) real at scale. If Apache Kafka is about capturing events, Flink is about understanding them: recognizing patterns, applying rules, aggregating, and emitting higher-order signals in motion.

Apache Flink is the production-grade engine for CEP at scale. If Kafka/Event Hubs capture the torrent, Flink understands it in motion—stateful patterns, joins, and windows with a CEP library that models rules as NFAs (ex. “three failed logins then a success within 10 minutes”). It runs distributed across a cluster with event-time semantics and durable state (ex. RocksDB), so out-of-order data and long sessions don’t break your logic. Patterns can run continuously across billions of events.

- Compared with Azure Stream Analytics (ASA): ASA is a solid service for lightweight CEP — tumbling, hopping, sliding, and session windows; counts and aggregates; a few dozen rules at most. It’s good at filtering floods of events down to something manageable. But ASA shows its limits: long-running transactions are hard, rule sets in practice begin to buckle beyond 50–60 (your mileage will vary), and logic remains fairly shallow. Flink is the opposite end of the spectrum: it was designed to support thousands of rules, complex branching patterns, and hours- or days-long sessions, all while scaling horizontally to billions of events.

- Penetration and adoption: Flink became an Apache top-level project in 2014 and is now used by some of the world’s largest stream-driven companies. Alibaba runs it at staggering scale, Uber built its real-time platform on it, Netflix relies on it for recommendations, and Amazon offers it as a managed service (Kinesis Data Analytics for Apache Flink). It isn’t niche; it’s one of the dominant engines for real-time AI plumbing.

Tying back to Figure 1, the architecture I sketched years ago as Reps—many models, rules, and recognizers compiled into NFAs and run in parallel over streams—is exactly what Flink delivers today. ASA can only gesture toward that vision; Flink fulfills it. More scalable, more robust in rules, and more expressive in workflows, Flink is the substrate where CEP finally has the chance to be recognized as a full member of the Assemblage of AI.

The example on my GitHub repository, SQL to load an NFA into Flink, is an example of SQL-like code that loads the NFA shown in Figure 3 into Flink.

Code 1 shows what an event stream would look like.

{“user_id”:”u1″,”state”:”Awake”,”ts”:”2025-09-25T22:00:00Z”}

{“user_id”:”u1″,”state”:”Light”,”ts”:”2025-09-25T22:10:00Z”}

{“user_id”:”u1″,”state”:”Deep”,”ts”:”2025-09-25T22:40:00Z”}

{“user_id”:”u1″,”state”:”REM”,”ts”:”2025-09-25T23:20:00Z”}

{“user_id”:”u1″,”state”:”WokeUp”,”ts”:”2025-09-26T06:30:00Z”

Code 1 – Stream of events for the NFA shown in Figure 3

Flink can handle at least the core parts of reptile intelligence very well. But there are certainly aspects I had in mind for Reps that were implemented at a basic level that I don’t believe are in Flink at time of writing. I plan to pursue reptile intelligence going forward with Flink as the core technology. However, there’s so much left to discover about how the systems of intelligence are structured that I’m not quite ready to completely mothball Reps.

Where Reptile-Level CEP is Used Today

Most of my colleagues have heard of CEP but aren’t very familiar with it. That’s even though it runs underneath many systems they touch every day. Vendors usually call it “real-time streaming” or “event pipelines” instead of CEP, which is why it stays invisible. A few prominent domains:

- Fraud & FinTech – CEP rules power real-time fraud detection in credit card swipes, instant payments, and e-commerce checkout flows. It’s watching for suspicious event sequences (location, amount, device change) and firing recognitions in milliseconds.

- AdTech & Personalization – Billions of ad-impression events are streamed through Flink-like engines to decide bidding, capping, or eligibility rules in real time.

- Ride-hailing / Delivery – Dispatching, surge pricing, ETA updates, and abuse detection rely on CEP to recognize event motifs across drivers, riders, and maps.

- Telco & Networking – CEP correlates floods of alarms into root-cause incidents and SLA breaches.

- Streaming / Social Media – Monitoring abuse patterns, engagement streaks, or trending content requires event-time recognition, not just batch analytics.

- AIOps / Observability / SIEM – CEP deduplicates alerts, enforces time windows, and detects patterns of system behavior across logs and metrics.

It’s generally under the radar and not considered “AI”:

- It’s usually described as “real-time infrastructure” or “streaming features”, not “AI.”

- CEP is plumbing — if it works, no one notices; if it fails, dashboards go dark.

- Its value is measured in throughput/latency, not in accuracy like ML models.

That’s why a good percentage of my colleagues haven’t heard of CEP, even though their companies are running it behind the curtain.

If you think in neurological terms, CEP maps nicely onto a layered view of the brain—but only as an analogy:

- ASA-like rules act as reflexes (the fastest, lowest-cost responses, similar to brainstem reflexes).

- Flink’s massively parallel NFAs are closer to the older subcortical/habit systems (the “reptile” layer and basal-ganglia-like pattern selectors) that run many recognizers in parallel and bias actions automatically.

- The limbic system analogy sits in the middle — reward, salience, and memory signals that decide which recognitions should be reinforced or suppressed.

- Above them all sits the slow, deliberative neocortex: the Prolog/System-2 of our architecture, where deep reasoning, explanation, and policy changes occur.

This framing ensures we remember the theme of Assemblage of AI—that CEP and Flink aren’t the whole brain, but they’re a vital part of the machinery that turns raw sensation into situational awareness and action.

Sources of the Rules

The big problem with CEP at this reptile level of intelligence is how the rules are created and maintained. This was the same problem with knowledge graphs. Teams of subject-matter experts and ontologists could take months or years to hammer out a KG, only to have it go stale as the world changed.

We’ve already seen what changes the game: an assistive technology that amplifies the component. In the case of knowledge graphs, it was the arrival of LLMs — accelerating what once took months into weeks. For machine learning itself, it was the rise of ML pipelines such as MLflow and Azure ML. Suddenly, designing and refining models no longer required every detail to be handcrafted; AutoML could try dozens of candidate structures and parameters in the time it would take a data scientist to build just one.

The point is that rules don’t have to be purely hand-authored anymore. They can come from other AI components that have been similarly enhanced. Yes, we can still write them ourselves, but it’s brittle — even if you take years to produce a Version 1.0, the world shifts under you, and an outdated model is worse than no model at all.

So where do rules for CEP actually come from? In the sections that follow, I’ll walk through a few major sources:

- Prolog versus NFA — contrasting deep deductive reasoning with fast sequence recognition.

- Machine Learning Models — which kinds can be mapped into a recognition fabric.

- The Semantic Web — RDF/SWRL rules compiled into NFAs for generalization and reasoning.

- LLMs — broad assistants that can suggest, translate, and test rules across domains.

Prolog versus NFA

Beginning with Prolog as a source of rules might seem like an odd place to start, given its reputation as a dinosaur from the old Expert System AI Summer. But Prolog—or any technology that carries its capabilities forward—is an essential part of AGI. I’ve written about this in the Prolog in the LLM Era series. It represents the deep exploration of rules. Since Prolog are rules that I recommend as part of the Assemblage of AI, well … it is a source of rules.

Both Prolog and NFA are rule systems, but they differ in character. NFAs are built for recognizing sequences — chains of events or symbols flowing through time. Prolog, by contrast, is computationally heavier. It dives deep into recursive nests of logic, reasoning step by step until it reaches an answer. Prolog is the space for deep deductive reasoning — where inference can chase itself as far down the chain as the rules allow — in contrast to CEP’s rapid but shallower recognitions.

This distinction doesn’t mean NFAs are limited only to sequential rules. With some adaptation, many rules that are not naturally sequential can be re-expressed as NFAs. That lets them be folded into the same recognition fabric as event-sequence rules and processed very quickly. In other words, NFAs give us a way to centralize and accelerate a broad mix of rules — not just “A then B then C,” but also certain logical conditions that can be mapped into state hops.

For example, a simple rule that isn’t naturally sequential:

IF-THEN statement:

IF Temperature > 100 AND Humidity < 10% THEN FireRisk

Prolog:

fire_risk(Temperature, Humidity) :- Temperature > 100, Humidity < 10.

On the surface this looks like a boolean condition, not a sequence of events. But you can adapt it into an NFA by treating each condition as a state hop:

- Start state → see

Temperature > 100→ move to state T. - From state T → see

Humidity < 10%→ move to accepting state FireRisk.

The order doesn’t matter; the NFA can be defined so that Humidity < 10% could arrive first, then Temperature > 100. Either path leads to the FireRisk state.

This translation lets a non-sequential logical rule ride in the same recognition fabric as genuine event sequences. The benefit is speed: the NFA engine doesn’t “think” — it just hops states until a rule is satisfied.

That’s why systems like Flink or Reps matter: they place all these rules into one fast, minimally stateful engine, delivering the equivalent of System 1 thinking — immediate, large-scale recognition. Prolog remains the domain of deeper deductive reasoning. Together they complement each other: NFAs for fast recognition across thousands of rules, Prolog for careful exploration when logic depth is required.

Machine Learning Models

With Reps the encoding of ML models was PMML (Predictive Model Markup Language). Today there are other ways we can serialize and deserialize ML models. For example, we can serial into the pickle format, then deserialize it later to interrogate model objects in Python. The list of ML algorithms that work are the ones that can be expressed as simple graphs that lay out paths.

Let’s get the most important ML algorithm, neural networks, out of the way. they won’t work here. the nodes and edges don’t have individually translated meaning. the workaround might be to flatten it by submitting combinations of discretized features (after they’ve been through the worm intelligence) and get the result. then the NFA is more like the association rules we’ll get to in a minute. Remember, most machine learning models is just a function that maps a set of features to some value.

Obviously, sequence ML models are most conducive to Reps since they are, well, sequences.

Decision trees are the next most conducive to Reps because it’s a tree where we go down a path towards each branch. Decision forests are the most intriguing because they are robust in recognizing from various sets of features.

Association rules (market basket) aren’t sequential. They are set membership. With Reps I did create the ability to create set nodes. It keeps firing until it receives a full collection and outputs that it has the collection or one 1 missing and it reports the missing one. This is about filling in a gap or naming something.

Regressions don’t work because they are formulas, graphs of decision points. However, a workaround is to find phase change points, which are the relevant breaks. For example, water temperature could be binned into <=32F, 33 to 211, and >=21 F. Although there are other thresholds (ex. medium-rare steak 130-135F), such other bins are use-case specific. However, if the use case has to do with people, we might have a bin that is BETWEEN 98 and 99 (a safe body temperature). this can be accomplished with worm intelligence.

Scatter plots and clusters are also about sets and values. We could bin values and collect a set of features (combination of regression and association). Clusters are very important because it’s actually about abstraction/generalization—very important concepts in handling a very complex world.

The Semantic Web

At its foundation, the Semantic Web is built on RDF (Resource Description Framework), a way to describe knowledge as triples: subject–predicate–object. For example: Eugene – is a – Person. These triples can be linked into a graph, where nodes are entities and edges are relationships. When this graph is curated, enriched, and given schema or ontology support, it becomes what we usually call a knowledge graph. The Semantic Web stack (RDF, RDFS, OWL, SPARQL) provides the standards and connective tissue for describing types, hierarchies, equivalences, and attributes in a machine-readable way. This makes it an ideal substrate for compiling into NFAs, since each predicate is already a kind of “if–then” recognition rule.

Simple NFAs can be compiled directly from a knowledge graph. The Semantic Web community has already given us useful connective tissue: predicates like is a, a kind of, same as, plus attributes and categories. Each of these can be turned into simple recognition rules. They may look trivial in isolation, but together they give us the building blocks for generalization—moving from specific instances toward broader categories and back again.

- “Is a” (type relationships)

- Knowledge graph fact:

Eugene is a Person. - NFA rule: if the event stream produces

Eugene, advance the automaton to thePersonstate. - Example:

Toyota is a Company. When an event mentions “Toyota,” the NFA can fire a recognition on “Company.” - Use: this lets recognizers generalize from instance-level signals (a person, a brand) to their type, which makes rules reusable.

- Knowledge graph fact:

- “A kind of” (taxonomy / hierarchy)

- Knowledge graph fact:

Sparrow a kind of Bird. - NFA rule: event mentions

Sparrow→ advance to stateBird. - Example:

Maple a kind of Tree. When an event says “Maple sap collection,” the NFA also fires “Tree,” letting rules that look for tree events activate. - Use: this supports hierarchical reasoning—catching not only the exact match but also its broader category.

- Knowledge graph fact:

- “Same as” (equivalence links)

- Knowledge graph fact:

IBM same as International Business Machines. - NFA rule: event mentions either label → transition to same canonical state.

- Example:

NYC same as New York City. A stream with “NYC Marathon” fires the same recognition as “New York City Marathon.” - Use: this normalizes across synonyms and aliases, preventing rule explosion.

- Knowledge graph fact:

- Attributes

- Knowledge graph fact:

Car has attribute Color. - NFA rule: when an event mentions

Car + Red, advance to a recognition likeRedCar. - Example:

Coffee has attribute Hot. An event “serve hot coffee” can activate both “Coffee” and “Hot,” letting temperature-related rules engage. - Use: enriches base categories with features, allowing finer-grained recognition.

- Knowledge graph fact:

- Categories (group membership)

- Knowledge graph fact:

Eiffel Tower in category Landmarks. - NFA rule: event mentions

Eiffel Tower→ recognition fires for bothEiffel TowerandLandmark. - Example:

Pythonin categoryProgramming Language. A stream mentioning Python triggers rules for both Python specifically and programming languages in general. - Use: allows rules to operate at the category level, generalizing signals without needing to list every member.

- Knowledge graph fact:

In practice, this means: if your event log mentions “Maple,” the NFA not only sees “Maple” but also “Tree,” and if it’s “IBM,” it also fires “Company.” These are tiny steps individually, but stitched together across thousands of facts they expand the recognition lattice—exactly the kind of generalization human intelligence relies on.

More complicated NFAs can be derived not just from static facts but from reasoning rules. The Semantic Web Rule Language (SWRL) lets you express if–then logic across RDF data. For example:

- SWRL rule: Person(?x) ∧ ParentOf(?x, ?y) ∧ Student(?y) → ParentOfStudent(?x).

- NFA equivalent: If the stream produces a sequence of facts where an entity is recognized as a Person, then linked by ParentOf to another entity, and that second entity is recognized as a Student, the automaton can fire a recognition for ParentOfStudent.

This pattern isn’t a simple one-hop transition — it’s a conjunctive rule spanning multiple relationships. Compiled into NFAs, SWRL-like rules create higher-order recognizers that activate only when multiple conditions co-occur. That moves us from trivial type lifting (“Sparrow → Bird”) to richer reasoning (“If X is a parent of Y and Y is a student, then X is a parent-of-student”).

Note: Both Prolog and SWRL are about reasoning, but they approach it differently. Prolog uses its own resolution and backtracking engine — an algorithmic counterpart to graph exploration — to evaluate rules encoded in declarative Prolog syntax. It searches dynamically through rules and facts to find solutions. SWRL, by contrast, reasons through rules expressed inside a knowledge graph, using RDF/OWL semantics to extend the graph with new inferences. In practice, Prolog is a logic engine that explores a rule space, while SWRL is a standards-based way to add reasoning into graph-based data.

LLMs

One of the primary themes in my books—Enterprise Intelligence and Time Molecules—is that LLMs can be of significant use, since they know tons of stuff about tons of topics. As long as we don’t push it into the bleeding edge, it’s a pretty good assistant.

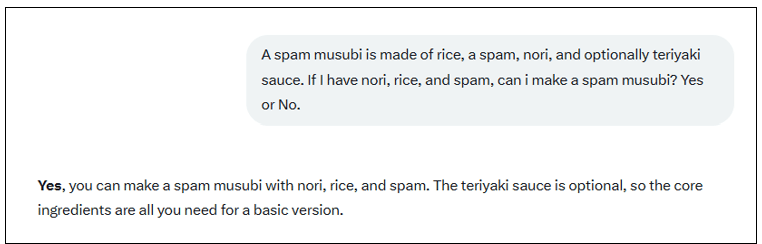

Figure 4 shows a quick example of how an LLM can perform “market basket” functionality. However, it’s still didn’t give me a “Yes or No”. That’s a problem. It has a mind of its own (so to speak) we can’t explicitly control.

I then asked Grok to create the PMML for the spam musubi. LLMs are good for that kind of thing …

Event Driven Architecture

Event-driven architecture (EDA) is the foundation of everything described in this blog. Rather than asking systems to pull for updates, events push themselves forward as soon as they occur. A sensor reading, a meeting transcript, or an AI agent’s action becomes a first-class event enterprise intelligence, as I discuss in Thousands of Senses. These raw events enter an event hub—technologies like Kafka or Azure Event Hub — which fan them out to any number of subscribers.

From there, transforms lift the events into more useful forms: speech recognition, computer vision, translations, or streaming analytics that recognize patterns. Some events are simple enough for Azure Stream Analytics — worm-level reflexes. Others demand the scale and flexibility of Flink — reptile-level recognition, complex event processing at industrial scale.

The outputs don’t vanish: they are stored as derived events in databases such as CosmosDB or Time Solution, where they can be analyzed, correlated, and fed back into new rules and models. Finally, consumers — dashboards, applications, or automated agents — act on these recognized situations.

Basic CEP Flow

In short, event-driven architecture is the circulatory system: every other component depends on it to carry signals, distribute them widely, and make them available for recognition and action.

- Raw Events: Everything that happens in the world (or apps) becomes an event: sensor ticks, page views, POS swipes, meeting transcripts, agent tool calls. Some devices do quick edge work (filtering, batching, light transforms) to cut noise and latency, but they don’t decide—yet. Each event is normalized to

{case, time, event, props…}so downstream systems can stitch sequences later (the Time Molecules sweet spot). - Event Hub (pub/sub fan-out) A durable, high-throughput bus (Kafka or Azure Event Hubs) that decouples sources from processors. Publishers push once; many subscribers pull independently—CEP, monitoring, archival, ML feature streams, etc. This layer gives you back-pressure handling, partitions for scale, and the freedom to evolve consumers without touching producers.

- Complex Event Processing (CEP): Streaming compute turns raw events into signals.

- Azure Cognitive Services: enrich raw media/text (ASR, vision, translation) into structured tokens you can reason over.

- Azure Stream Analytics (ASA): “worm intelligence”—fast filters, windows, aggregations, and a small set of regex-like patterns over streams. Perfect for simple detections and KPIs.

- Apache Flink (on AKS / managed): “reptile intelligence”—richer sequence logic (stateful patterns, joins, CEP libraries). Think NFA-style multi-step patterns with loops, time bounds, and branching. The output of CEP is higher-level events: “keyword_detected”, “threshold_breached”, “sequence_matched”.

- CEP Consumers (state, actions, orchestration) Downstream systems react to those signals:

- Azure Cosmos DB to persist events and derived facts; Change Feed wakes up processors whenever new items land.

- Time Molecules builds Markov models and time stats from the event fabric (per process, slice, and segment).

- Azure Functions / Durable Functions implement the action layer: alerting, ticketing, graph updates (Neo4j), calling agents/RAG, fanning-out work, retries/compensations. This is where you can trigger LangChain/LangGraph/Semantic Kernel flows for planning + tool use, then write results back.

- Submit output as an event (the feedback loop) Every conclusion or action becomes another event on the bus—“insight_found”, “recommendation_issued”, “model_scored”, “config_changed”. That closes the loop: actions influence future streams, sequences grow richer, and Time Molecules sees how interventions change transition probabilities over time.

Item 5 is what raises us from robust recognition to iterative recognition. Recognitions emit back into the bus (Change Feed/Event Hub) so rules, KG facts, and actions can iterate—closing perception→action.

An event hub (ex. Kafka) is a distributed append-only log where everything that happens—clicks, IoT pings, CDC rows, model scores—arrives as events. Producers write to topics that are sharded into partitions; a key like CaseID keeps related events in the same partition so order holds where it matters. Consumer groups pull the stream independently, each tracking its offsets, which means you can replay history to rebuild pipelines, roll out new logic, or regenerate features and models—deterministically.

Why it’s critical in this architecture:

- Decoupling. Producers don’t care who’s listening; consumers can come/go, scale out, or be replaced without retouching sources.

- Scale & throughput. Partitions parallelize reads/writes; backpressure is absorbed by the log instead of toppling upstream systems.

- Ordering where you need it. Per-key ordering keeps sequences coherent for Time Molecules and process mining.

- Retention & auditability. Data isn’t “consumed away”; you keep a time window (hours→months) to reprocess, compare before/after changes, and prove lineage.

- Ecosystem glue. Connectors move data between DBs/warehouses; a Schema Registry stabilizes event contracts; stream processors (Streams/ksqlDB/Flink) let you join, window, and aggregate in motion.

Time Molecules

The content of my book, Time Molecules, plays heavily in this blog because a fundamental aspect of it, Markov Models, are a natural source of NFA. Time Molecules are about process, workflow—and they are pretty sequential.

I won’t cover Time Molecules deeply here—it’s in the Time Molecules book. But here are a couple of references from older blogs:

- Sneak Peek at My New Book—Time Molecules

- BI-Extended Enterprise Knowledge Graphs: Contains a good overview of the Time Molecules book.

With NFAs that can recognize something and NFAs that keep track of a process, we have the two necessary ingredients for decoupled recognition and action. In a nutshell, we first recognize a situation, such as seeing a bear. Most critters will automatically run the other way. That can sometimes be the wrong thing to do. Instead, we humans can iterate through our options (quickly) and select what is hopefully the most optimal action to take.

Parallel Processes

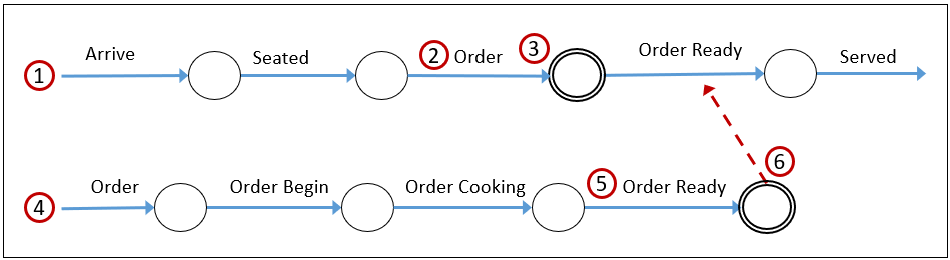

Figure 5 is a simple example of an NFA. It’s a restaurant process consisting to two processes:

- Customer walks in.

- Customer orders.

- Order event is fired with caseID.

- Order event triggers prep of order.

- Order is ready.

- Order Ready event with caseID is fired. orders.

The Order event doesn’t just advance the customer process, it also triggers the kitchen process to begin. Both processes move forward in parallel until they synchronize again at Order Ready, when the customer can be served.

This concurrency is explicit in Petri nets, with tokens flowing down both paths and meeting back together. It’s what makes Petri nets especially effective for modeling real-world processes that branch, run in parallel, and rejoin. Petri nets have built-in capabilities that Markov models and NFAs lack—most notably, they can naturally express parallelism and synchronization.

Petri Nets

Why not Petri Nets? In the process mining world, Petri nets are the canonical output. But in Time Molecules I chose Markov models instead. The reason is the same as for OLAP cubes BI: pre-aggregations are not the final charts — they’re the structures you build charts from. Markov models play the counterpart to OLAP pre-aggregations. They are efficient to compute, easy to slice, and give you the raw material for insight. They are the optimization of the process-centric side of BI.

Petri nets, by contrast, are more like the final visualization or report. They show the discovered process in a clean structural form, much like a dashboard shows a KPI in a polished chart. Useful, yes — but they sit on top of something else. In practice, you can use Markov models to build Petri nets, just as pre-aggregations build dashboards. My focus in Time Molecules is on the raw material: the Markov “cubes” that let you analyze process behavior directly, rather than on the polished Petri-net picture that often comes at the end.

In the blog, Beyond Ontologies: OODA Knowledge Graph Structures, I discuss the process of converting Markov models to NFA.

Figure 6 shows the Petri Net equivalent of the NFA shown in Figure 5 above.

Figure 6 was generated by customer_order_petri.py

Future Topics

Of course, this is just an introduction to a direction I spent much time on since about 2008 (mostly 2014-2016). We’ll discuss other aspects, for example, these important topics:

- Governance in CEP isn’t just about speed but about trust. Every recognition rule or model should be monitored for false-positives (how often it fires without a real event), with thresholds that trigger review. Inhibition and timeout rules can dampen over-eager patterns by requiring sustained signals or pausing after a trigger. And because some rules will inevitably prove wrong, rollback mechanisms matter: rules and models need versioning, audit trails, and the ability to disable or revert quickly without halting the whole stream. This ensures that CEP systems scale not only in throughput but also in accountability, safety, and resilience.

- Model Context Protocol (MCP) is designed to be the bus that connects LLMs with external data and tools. In practice, that means the layers I’ve been describing—reptile-level recognition in CEP/Flink, symbolic reasoning in Prolog and SWRL, grounding in knowledge graphs and BI structures like ISG/TCW—don’t have to be hard-wired together. MCP gives them a common protocol for context sharing. It looks like MCP be the connective tissue that allows the Assemblage of AI to assemble.

A Word on Context Engineering

Context engineering is a newly emerged term in AI (seems to have gained traction around the June 2025 timeframe). It’s the systematic design of the entire environment an AI works inside—what information is retrieved and trusted, how it’s chunked, ranked, formatted, and sequenced; what memory is persisted, and which tools the model can call—so it reliably achieves a task over many turns. It complements prompt engineering (the instruction text) by supplying the right evidence at the right time (RAG), maintaining session and long-term state, enforcing output contracts (ex. JSON schemas), and grounding answers to reduce drift and hallucinations.

A more concrete way to see this: imagine an ER patient arriving with stroke symptoms. Multiple tests kick off almost at once—CT, labs, EKG—each with its own specialist and its own AI assistant. Those assistants don’t work in a vacuum: each receives the patient’s current chart, and each knows what the next steps usually need. So while the CT assistant summarizes its findings, it also includes the bits the downstream “integrator” will rely on (time window, confidence, flagged anomalies, links back to source images).

Likewise, if the lab assistant spots an out-of-range value that typically changes the CT read, it forwards that signal immediately. In other words, the workflow itself carries what we should term context contracts: For every step, a short description of what it does, what it needs, what it produces, and which details should be preserved for the next step. With those contracts in place, parallel paths stay coordinated, hand-offs are light but intentional, and the final analysis agent doesn’t have to re-hunt for evidence—it’s already been curated on the way.

In a future blog, I’ll discuss how my book, Enterprise Intelligence, supports this newly emerged notion of Context Engineering. For now, my blog, Embedding a Data Vault in a Data Mesh – Part 1 of 5, describes this one-two punch approach as the most effective way to accelerate the onboarding of the data across what could be hundreds of domains across an enterprise. That integration of data across the far reaches of the enterprise is the first step.

Closing Reflection

CEP never got its AI summer. It lived in the shadows while Big Data, the Cloud, data science, deep learning, and now LLMs all took turns in the spotlight during its lifetime. Yet CEP has always been there, quietly integrating rules, workflows, and recognizers into living processes.

Now, as the LLM-driven Era of AI levels off to the point of diminishing returns (simply more “parameters” and/or larger context windows yields greater AI performance), we have the cycles to explore the need for integration beyond text becomes obvious. CEP is poised to step out from the background—not as a just “that thing for real-time”, but as a first-class AI component. It’s the connective fabric that allows thousands of models, rules, and events to work together. In the Assemblage of AI CEP deserves its place at the table.

Flink is not “THEE” AI. It doesn’t give us the full span of human intelligence, not even all that I’d expect from reptile intelligence—the inhibitory synapses, optimizations, strange shortcuts and feedback loops that brains discover for themselves in ways we don’t yet understand. But the concept of Flink, scaled-out along the dimensions of processing speed and the number of rules is a component of full AGI.

For now, that is more than enough. Flink serves greatly as a dependable workhorse for real-time recognition—detecting fraud, orchestrating IoT, powering personalization, monitoring systems. It takes streams of raw events and turns them into actionable situations at scale, a capability that most enterprises desperately need today.

For the entire life of CEP, this capability has lived in the shadows, treated as plumbing rather than intelligence. Yet if we’re serious about assembling AI, we can’t ignore it. CEP and engines like Flink that implement it at scale—process a massive number of events across a massive number of rules—give us one of the few working, industrial-scale components that look and feel like cognition: streams of signals flowing into networks of recognizers, firing, inhibiting, and composing into higher-order meaning. That doesn’t make Flink the brain. But it is one of the missing pieces in the process of intelligence.

However, after all that said, strictly speaking, I’m not talking about simply an AI summer for CEP. I don’t see CEP/Flink alone as the future of AI. CEP/Flink runtimes are pretty much good enough for worm intelligence, and with scale, even reptile intelligence. But to reach the level of AGI the “AI powers that be” are so vigorously seeking, I see CEP/Flink, plus LLMs, plus knowledge graphs, plus machine learning, plus rule-based expert systems—assembled into a system of intelligence—as the future of AI.

Now that we’ve discussed implementing and integrating massive numbers of rules to mimic reptile intelligence, let’s see how stories are the transactional unit that elevates we humans to our level of intelligence.

Notes

- This blog is Chapter VI.3 of my virtual book, The Assemblage of Artificial Intelligence.

- Time Molecules and Enterprise Intelligence are available on Amazon and Technics Publications. If you purchase either book (Time Molecules, Enterprise Intelligence) from the Technic Publication site, use the coupon code TP25 for a 25% discount off most items.