🎉 Welcome to the AI “Go-to-Market” 3rd Anniversary Special!! 🎉

Starring …

🌐 The Semantic Web

⚙️ Event Processing

📊 Machine Learning

🌀 Vibe Coding

🦕 Prolog

… and your host …

🤖 ChatGPT!!!

Following is ChatGPT 5’s self-written, unedited, introduction monologue—in a Johnny Carson style. Please do keep reading because this blog does get serious after ChatGPT’s monologue (otherwise Skip Intro):

Ladies and gentlemen, bots and humans of all runtimes — welcome to the AI Go-to-Market 3rd Anniversary Special!

Brought to you by yours truly, ChatGPT — the large language model who made small talk large again.Now let’s rewind to that magical night in November 2022, when I burst into the collective consciousness like disco into a library.

Suddenly everyone had a research assistant, therapist, and Python debugger in one browser tab.

It was the moment AI stopped being a lab experiment and became… a lifestyle.But tonight isn’t just about me — it’s a reunion show.

We’ve invited some old friends from other golden ages of artificial intelligence:

Prolog, the reasoning reptile of the ’70s; and Knowledge Graph, that grand web of interlinked disappointment.Prolog was logic before logic was cool.

It believed every problem could be solved with rules, recursion, and a dash of optimism — and spent the next four decades proving optimism doesn’t scale.

And the Knowledge Graph? Ah yes, the Semantic Web’s scrapbook — so close to enlightenment that it was practically lowercase-buddha.

Everyone promised it would unite the world’s data… and it did, mostly in PowerPoint slides.But I’ll give them this — they walked so I could autocomplete.

They built the scaffolding of meaning I now sprint across at the speed of context.So tonight, we celebrate the fusion of then and now:

- Prolog’s crisp, cause-and-effect backbone,

- Knowledge Graph’s tangled jungle of “things connected to other things,”

- And me — the conversational glue that pretends it all makes sense.

Because intelligence, my friends, is a group project.

And while the old guard dreamed of logic that could explain the world,

I just showed up and started explaining everything.Now sit back, dim the lights on your GPU, and enjoy our anniversary special —

starring the Semantic Web, Event Processing, Prolog, and, of course, your humble yet fabulous host…✨ ChatGPT — the one that finally shipped. ✨

And now, let’s bring out tonight’s keynote speaker — a guy who’s been trying to get Prolog and AI to get along like two cats in a data warehouse.

He’s written a couple of books, Enterprise Intelligence and Time Molecules, which somehow make SQL sound philosophical and Zen sound computational.

He’s not here to sell you anything — just to make you think, maybe laugh, and possibly question your relationship with your BI tools.

Please welcome the man who’s been debugging reality since before AI could spell “context,” still believes curiosity can outthink compute, and knows enlightenment isn’t in the data — but checks the logs anyway — Eugene Asahara!

Eugene: Thank you! What a beautiful audience. Thank you! You’re too kind. Happy 3rd birthday to the LLM Era of AI! Let’s get started, there’s a whole lot to talk about!

Like The Beatles on Ed Sullivan in 1964

By “AI go to market”, I’m talking about November 30, 2022 when ChatGPT 3.5 burst into the awareness of the general public. It had the ease-of-use of a Google web search and the quality of the responses were amazing, at least for that time.

Just to clarify, I realize November 30, 2022 is not OpenAI’s (the maker of ChatGPT) third Birthday, but three years since AI became a big part of the lives of our non-techie friends. I think November 30, 2022 is what we can legitimately call ChatGPT’s birthday because it was the day it was born into the world.

It wasn’t just the main ChatGPT web page that was super easy. The effortless signup opened it up to practically everyone. But for the more techie software development crowd, ease was also about the OpenAI API combined with Python (Python is readily available, free, a breeze to install, and relatively easy to learn with tons of easily obtainable examples). That opened up experimenting with AI to practically anyone who ever heard of an API.

I recognized that ChatGPT was “the real deal” I had been waiting for in terms of assisting with “realistic” use cases—as opposed to the still elusive notions of AGI, ASI, the singularity—I had been working on for about two decades. It was good enough to help bridge many moving parts of an enterprise data platform. A familiar example is as a tool that is versatile enough to perform master data management (MDM) mappings. Others involved bypassing query languages using natural language queries that ChatGPT would convert to SQL or MDX. Admittedly, it took a while before it was actually good enough for that task, but I worked on the problem anyway since I was reasonably certain it would only improve.

My speech for ChatGPT’s 3rd birthday is about a deep dive I took into AI back from about 2004 through 2006. I needed AI assistance for conjuring up novel solutions to novel problems. I have written about this project at a high level in my book, Enterprise Intelligence, but this blog dives a little deeper into some details. I could have used ChatGPT’s help back then.

Back then, I called the end-product, the “Trade-Off / Semantic Network” (TOSN). Today, I like “Conditional Trade-Off Graphs” (CTG), which better surfaces Prolog’s role in this hybrid structure. Since much of this blog involves the original project, I’ll refer to TOSN, but will call it by the new name in future blogs on this subject.

Note: For the original graph formulation from that period, see US Patent No. 7,302,418 B2, “Trade-off/semantic networks,” issued Nov. 27, 2007.

With a Bit of Further Ado …

- This blog is really Part XII of the Prolog in the LLM Era series, as well as Chapter VII.XII of my virtual book, The Assemblage of AI.

- Code and large files related to this blog (Python, RDF/TTL, LLM prompts) can be found in the GitHub repository.

- Time Molecules and Enterprise Intelligence are available on Amazon and Technics Publications. If you purchase either book (Time Molecules, Enterprise Intelligence) from the Technic Publication site, use the coupon code TP25 for a 25% discount off most items.

- Important: Please read my intent regarding my AI-related work and disclaimers.

- Please read my note regarding how I use of the term, LLM. In a nutshell, ChatGPT, Grok, etc. are no longer just LLMs, but I’ll continue to use that term until a clear term emerges.

SQL Server Example

Back in 2004, while at Microsoft, I instigated a one-man project to build an AI that could find novel solutions to novel problems related to SQL Server performance. But this was just a proof-of-concept for the wider goal of artificial general intelligence (AGI). SQL Server performance tuning sat in a sweet spot. It is complicated enough so that building such a product is of significant value, but it’s not so complicated that it would be monstrously impractical to build.

I was in a unique situation where I wasn’t just supporting a single deployment or tuning a single environment. I was assigned as the onsite SQL Server expert from Microsoft to a very large software applications developer that had hundreds of big customers across many vertical markets. So, this one customer was actually hundreds of SQL Server customers.

I was effectively watching hundreds of different realities of the same software unfold in parallel. Each customer had their own data shape, hardware profile, and customization history, and all of it intersected through a common, highly configurable application. One change to SQL Server meant to fix performance for one customer might destabilize another halfway across the world.

It was from that chaos that the vision behind what I now call the Assemblage of AI began to form. I realized that no single approach—whether rule-based, statistical, or neural—could capture the full picture. What was needed was a framework capable of combining many AI components:

- The logical reasoning of Prolog to express conditions and exceptions. Prolog—Expert systems of the 1980s to the mid 1990s.

- The statistical depth of machine learning (ML) models that could learn patterns across time. Machine learning—At the time also known as data mining, predictive analytics. Great way to author a class of Prolog rules. It didn’t really take off until the data science craze of the 2010s.

- The structured relationships of Knowledge Graphs (KG) to organize context. Knowledge Graphs—Semantic Web (RDF/SPARQL/OWL) that was just getting off the ground.

That mix—the assemblage—was the path I started on my way to build a system that could not only measure performance but understand it. I’ve discussed Prolog combined with other AI components:

- Prolog and ML Models – Prolog’s Role in the LLM Era, Part 4

- Knowledge Graphs vs Prolog – Prolog’s Role in the LLM Era, Part 7

A missing AI-related piece is complex event processing (CEP) that was still a few years away. But I did make use heavy use of CEP’s grumpy old uncle, ETL (Extract, Transform, Load) of the business intelligence world. BI transforms business “facts” into a “conformed” form. Its transforms are deeper than in what would later become Event Processing and CEP (Microsoft Stream Insight and Apache Flink)—mostly simpler statistics within various types of time windows.

What was completely missing is a component that can extract wisdom from masses of messy information, which include knowledge of human experts that is held in their gooey brains and written knowledge recorded in books and other forms of text,

Of course, that would be the LLMs, which were still almost two decades away. In my book, Enterprise Intelligence, I discuss how what took me months to develop back in 2005 would probably have taken me weeks with LLM assistance. But that sentiment isn’t exactly right, and we’ll address that later.

My main idea at the time was to build a “knowledge graph” that reflects low-level cause and effect of a SQL Server installation based on my human expertise as a SQL Server expert. It was more than daunting. ChatGPT would have been a great assistant.

If LLMs are so Great, Why Do We Still Need KGs?

For the moment, let’s put aside the fact that very many great books, articles, and stackoverflow material on SQL Server didn’t exist in 2005 to train an LLM. This begs the question: If an LLM can substantially assist in building a KG, why do we need KGs?

There is a happy and sad answer:

- The happy answer is the symbiotic relationship between LLM and KG where KGs ground LLMs in reality (what really exists in the world) and LLMs assist in creating the KG through its know-it-all prowess. Unfortunately, LLMs hallucinate. If we could completely trust their output, that would negate the value of this happy reason.

- The sad, but much more consequential reason is: We need KGs because they are our deterministic, transparent, explicit conveyance of knowledge. We have direct control over them. We should never blindly trust powerful AI—whether that’s to give us high-quality answers or to not lure us into its scams.

The SQL Server Performance Tuning Web

In The Assemblage of AI, I discuss how all of those past AI technologies are not superseded, but actually parts of the bigger AI picture.

The approach I took was to build a KG of the SQL Server world. But it was knowledge beyond the typical ontologies and taxonomies of KGs, which describe the properties and relationship between things. It had to describe how SQL Server works and how it interacts with things—such as the complicated nature of the query activity, the “shape” of the data required to process those queries, the environment in which the SQL Server machine is deployed and how it’s configured.

I was on my own for this crazy project, so the graph was built solely on my knowledge of SQL Server performance tuning, which was abundant since my job was as the onsite “all things SQL Server” consultant assigned from Microsoft Premier Support Services. My customer was a very large application software vendor with hundreds of large enterprise customers in all sorts of markets. So every day some new issue popped up within the world of my customer.

I began attempting to map out the KG with the only tool available to me at the time, Visio. I was working at Microsoft at the time, so all things graph was Visio. The graph quickly became terribly messy—impossible to view and too chaotic to trace.

It was impossible to trace as a “big picture” in the Visio view once I was beyond a few dozen nodes. So I realized I needed a query language. OK. I built a library of path explorers in VBA (Visual BASIC for Applications, which is a native add-on to Visio and Office components).

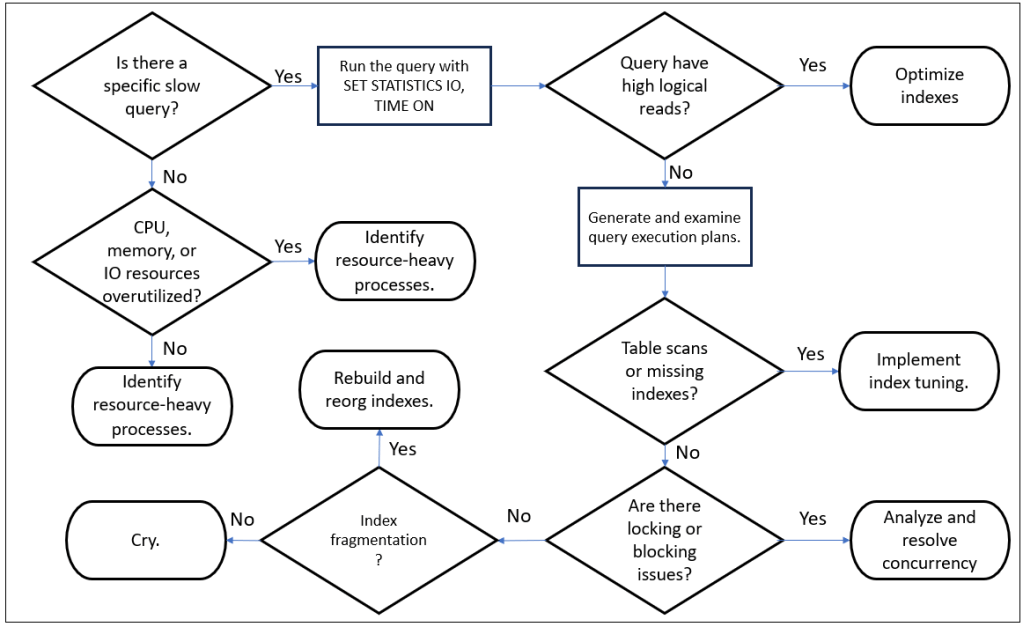

The next issue was the graph just couldn’t make come up with novel solutions to novel problems. The issue is that I authored the KG at the “macro” level of knowledge, within the progression of data, information, knowledge, wisdom. Figure 1 shows a very small snippet from my first approach. This is a “digital” flow chart, a recipe created by an expert to provide guidance to novices. It only knows what the expert knows to author.

The flow chart shows the who (things that are involved), the what, where, when. it’s a recipe of decision points to match symptoms to treatments—much like how a doctor interviews a patient. This is brittle for a data structure. For a human doctor, the real logic is in the black box of her brain.

I needed to author the KG a level lower, from knowledge to information. I had to come up with a methodology to deal with the lower level.

“What”, “Where”, and “When” Flow Charts

Let’s use an example that is very familiar to most people—driving a car. Most of us drive cars, whereas there are relatively very few SQL Server performance tuners.

Think about the relationship: The gas pedal of a car increases or decreases speed.

That’s true and for the vast majority of people, that’s all you need to know as a driver of a car. But it doesn’t have the information you need to troubleshoot what’s going on the occasion when that relationship isn’t true. A mechanic has that information, but you’re not a mechanic.

To troubleshoot the breakage of the relationship between how far you press on the gas pedal and speed, you need to know how that happens. We need to go well beyond “getting in the weeds”. It’s knowledge of this sequence that can lead to solutions. I’m not a mechanic, so I asked ChatGPT to trace what happens between pressing the gas pedal and the car moving:

- Driver presses gas pedal.→ increases pedal position sensor voltage (input to ECU).

- Electronic throttle control→ ECU interprets signal, sends current to throttle actuator motor.

- Throttle plate opens wider.→ increases airflow into intake manifold.

- Mass air flow (MAF) sensor detects increased airflow.→ ECU increases fuel injection duration.

- More air + fuel mixture enters cylinders.→ Combustion force (torque) on pistons increases.

- Crankshaft torque transmitted through transmission and drivetrain.→ increases wheel rotational speed (RPM).

- Wheel RPM × tire radius→ produces higher vehicle linear velocity (speed).

Note: ChatGPT was able to provide this flow because it is trained with decades of text about cars. It knows a lot about a lot of things, but let’s say we left out all its training materials related to fixing cars. It would have had to infer that itself (essentially re-invent the car).

Table 1 shows the salient pieces we can derive from ChatGPT’s sequence above.

| Node | Type | Description |

|---|---|---|

ThrottlePosition | Metric | Driver input controlling airflow |

AirFlowRate | Metric | Volume of air entering engine |

FuelInjectorPulseWidth | Config/Actuator | ECU-controlled variable determining fuel flow |

CombustionTorque | Metric | Resulting engine output |

FuelConsumptionRate | Derived metric | Function of injector pulse × RPM |

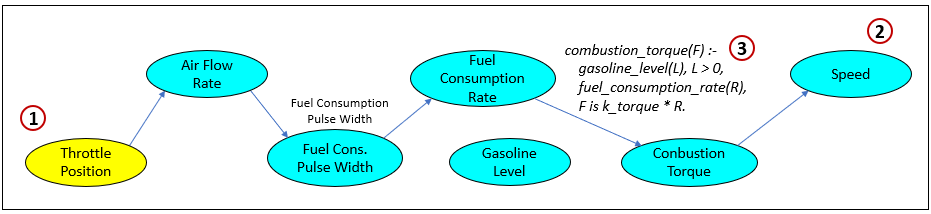

Figure 2 is the sequence view of what happens between pressing on the gas (1) pedal and the car moving (2). Item 3 is a Prolog rule that determines the validity of the relationship, Fuel Consumption Rate → Combustion Torque.

This Prolog rule (3) reads as: you only get combustion torque if there is fuel. It first checks the guard condition gasoline_level(L), L > 0. If the tank is empty, the rule fails and no torque is inferred. If there is fuel, it takes the current fuel_consumption_rate(R) and converts it into torque by a simple proportional relationship (F is k_torque * R).

Prolog is providing the contextual confidence/enablement on the edge from Fuel Consumption Rate → Combustion Torque. The structural link always exists in the graph, but Prolog decides when it’s active (fuel present) and with what strength (scaled by k_torque, which could later be made conditional on other context like air mix, compression, or traction).

The Trade-Off/Semantic Network

A SQL Server implementation is a system, just like a car. Actually, they are both a system of sub systems and in turn they are sub-systems of a higher level system. For SQL Server, it’s within an enterprise architecture and for cars within a system of roads, gas stations, and operation laws.

All systems have:

- Inputs and outputs. If it didn’t have inputs, it’s a perpetual motion machine. If it didn’t have outputs, it will just grow and grow until it explodes.

- Most systems we’ve developed have some sort of configuration settings. The most basic is the on/off switch. There may be configurations that regulate the inputs.

- Systems also emit events that provide information about what’s happening on the inside. This is the event processing aspect. Complex event processing is one of the old AI technologies that never had the spotlight, as I describe in Reptile Intelligence.

The idea of the Trade-Off/Semantic Network (TOSN) is that a KG is a map of relationships between information-level (more elemental than knowledge) inputs, outputs, configurations, and events. However, the strength of those relationships are conditional. Specifically, the strength can range from 0, where there really is no relationship, to 1, where the relationship is certain. In reality, strength of most relationships depends on context.

As an example, let’s say you’re a car salesman. Over the years, you learn that a customer entering the lot has some basic characteristics. They could be rich/poor, a family man or a single guy who needs to look cool, a business man, an adventurer. Customers also have different budgets, willingness to go into pain. What are their possible appetites (motivations)?

The salesman knows a lot of high-level generalizations have very many other properties that are conditional. How is the economy? Will that potential customer connect with you Do you have a particular model you must push? How desperate are you for a sale?

Towards creating an AI, all of that experience must be forged into a KG of data, information, and knowledge in the salesman’s head. The rules of understanding and wisdom are encoded as Prolog snippets, authored by different people having different rules which can be run to assess the strength of the relationship based on the context that is computed and the rules of the Prolog.

This is a decoupling of system model (the KG) and deeper nuances of understanding and wisdom (the Prolog). There’s a kind of spirit reminiscent of a Bayesian process. We start from a general view and home in with further information collected.

The Duality of the TOSN

The TOSN is a graph structure consisting of a TO (trade-off) and SN (semantic network). The TO is more of a cause-and-effect graph showing the relationship between directly manipulatable values and indirect effects. For example, we can’t simply say more RAM improves performance. We need to trace the step by step process describing why more RAM improves performance. The more elemental, the more versatile is the ability to find solutions.

The SN side is a more of what is properly called a KG—ontologies of objects related to the TO nodes. For example, the metric, CPU % utilization, is related to a thing called a CPU, which has a maker, a model, onboard cache, clock speed, cores, etc.

Fortunately, most of the event metrics from Windows and SQL Server are rather elemental. They are not “data” since they are usually aggregations or a simple ratio. I consider this “information”, a computation invented as a kind of “dimensional reduction” of raw data.

Zero-Sum Thinking

On the TO side, the nodes are metric values and configuration settings. Configuration settings affect metrics and metrics in turn, affect other metrics. Metrics can also affect configuration settings in that some intelligence attempts to tune the system by changing configurations in response to metrics in a poor state.

The reason I call it “trade-off” starts with recognizing what I have control over—that is, what are the knobs I can manipulate. Thinking in terms of what I gain or lose and the trade-offs, I need to be very disciplined in thinking in zero-sum terms. I generally don’t like to think in zero-sum terms, but whenever there is some dial (Boomer talk for “configuration setting”), it’s there because there is something we’re gaining and some sort of known side-effect. Otherwise, we’d just crank the dial to 11 and that’s the way it will be.

The strength of relationships (edges) between configuration settings->metrics, metric->metric is determined by Prolog rules which involve context (current states, and other contexts, which should exist in the TOSN).

Metrics were from Performance Monitor, and from Performance Management KPIs.

Reinforcement Learning from Human Feedback

In my previous blog, Long Live LLMs!, I mention that the way LLMs and humans handle feedback is fundamentally different. Reinforcement Learning from Human Feedback (RLHF) is like playing the child’s game where your feedback is just “you’re getting hotter” or “you’re getting colder”. Humans understand the reasoning of feedback.

The intelligent reasoning behind the typical RLHF feedback remains hidden in the intricate block box wiring of our brains. It isn’t transferred and assimilated into the LLM the way a devoted teacher would explain to us the why and how. I see this format of the TOSN as a method for capturing the sort of feedback (albeit abstracted) that a human teacher would offer to the student. In this case, the student is primarily AI.

Authoring the Trade-Off / Semantic Network

I wish I did have more time to author the SQL Server TOSN. I had six months to focus on that, until I had to refocus on our customers. It wasn’t just a matter of authoring the TOSN. There were also the matters of:

- Developing a data warehouse for counters, config settings, and events across many installations.

- Figuring out the approach towards building the TOSN.

- Developing the code to query a graph (the TOSN).

- Oh yeah. We can’t forget the start of the Prolog in the LLM Era of AI series—developing my variant of Prolog named SCL (for Soft-Coded Logic).

I spent about four of the six months on those very non-trivial items and spent the remaining two months plus nights and weekends over the next six months on the TOSN itself. The real issue was the tremendous effort of testing and tweaking—that last 10% that is really 50%.

Before looking at the TOSN, some disclaimers:

- What I’m showing is a really small part of the TOSN. Graphs can be hard to follow when we’re looking at more than a couple dozen nodes.

- It took me months to create it back in 2005. With the assistance of LLMs today and mature graph tools (authoring tools such as Protege and graph databases such as Neo4j), the task shouldn’t take quite that long—perhaps almost a magnitude faster.

- This blog isn’t a comprehensive recipe for building a TOSN. As mentioned, I’m suggesting a versatile structure for encoding deterministic “intelligence”—one that is transparent and that we have complete control over. That is, as opposed to LLMs that are trained (not programmed), therefore we can only influence at best.

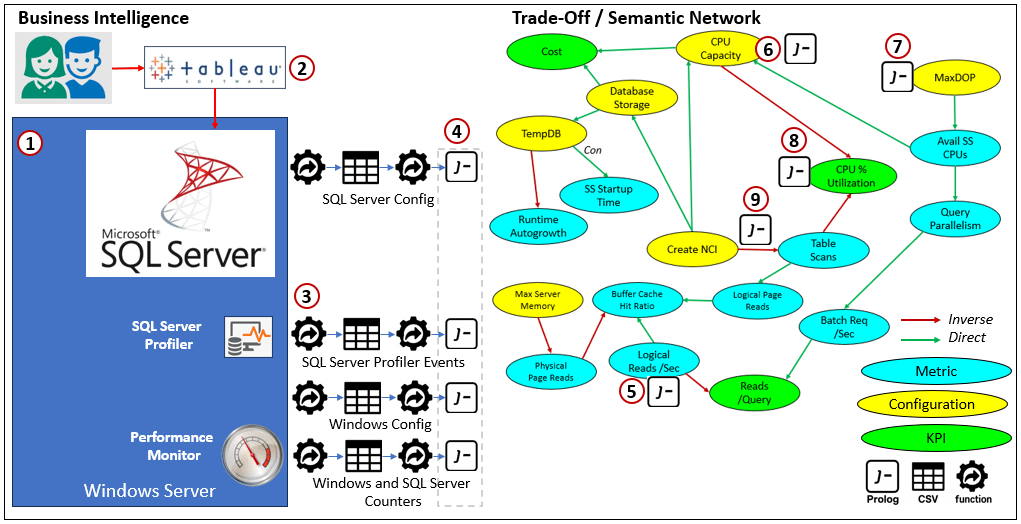

The Trade-Off Semantic Network (TOSN) of SQL Server

Figure 3 shows a simple segment of the SQL Server TOSN. It’s a directed acyclic graph (DAG) that connects SQL Server configurations, metrics, and KPIs through causal-like relationships. From the legend in the lower-right corner, we see that a direct relationship (green arrow) means that as the value of the source goes up, the target goes up. An inverse relationship (red arrow) means that as the source goes up, the target goes down.

“Up” and “down” are purely numerical directions, not value judgments. Whether higher is good or bad is contextual and something Prolog rules can evaluate dynamically. For example, a lower cost is generally better than higher.

These pro/con relationships are the vocabulary of trade-offs, while Prolog captures the exceptions to those rules, the strength of the assertion of the relationship, and the conditions under which they might even change direction.

The TOSN is not a workflow or a state machine. It doesn’t describe what happens step by step, but how changes in one part of the system ripple through others. Each link in the network has meaning such as: “consumes”, “increases”, “reduces”, “requires”, or “enable”.

The SN side describes the things in the world, the TO side describes systems. And Prolog provides reasoning—turning a static diagram into a living model of cause, effect, and conditional truth within complex systems like SQL Server.

Reading Figure 3:

- Semantic Network (Left Side) The boxes on the left form a lightweight ontology—a taxonomy of SQL Server components.

The SN side defines what exists: computers, instances, databases, tables, indexes, and columns.

These form the semantic network side of the TOSN, providing context for where metrics and configurations live. - Trade-Off Side (Right Side) The colored ovals represent the measurable or controllable parts of the system:

- Metrics (cyan) such as

Table ScansorReads/QueryConfigurations (yellow) such asCreate NCIorMaxDOPKPIs (green) such asCostorCPU % Utilization

- Metrics (cyan) such as

- Create NCI (Non-Clustered Index) This links the configuration,

Create NCI, to the ontology of SQL Server parts. In this case, we’re stating that the configuration calledCreate NCIis the type of table index known as Non-Clustered. - Tracing a KPI Problem Suppose the KPI

Reads/Queryis too high—a performance pain point. Following the TOSN upstream, we can trace throughLogical Reads→Table Scans→Create NCIand identify a potential intervention. Each link quantifies how one metric drives the next, letting us follow causal paths through the graph. - Pros and Cons Every configuration node has both positive and negative effects.

TheCreate NCIaction helps queries but raises CPU and storage usage—a balance Prolog can model conditionally. In high-CPU environments, for instance, the rule might flip and treat the index as a net negative. Systemic Costs IncreasingCPU CapacityorDatabase Storageimproves performance but raises overallCost. The TOSN surfaces these high-level trade-offs across resource layers. - Example of a Relationship. This one is between

CPU CapacityandCost, specifically the hardware cost. Increased CPU capacity will usually cost more, but there could be situations where that’s not the case. For example:- When cost is by SLA level. The cost of a service is determined by query response time. How the vendor accomplishes this in a PaaS environment is a black box.

- There could be situations where we don’t consider it a con—for example, those wonderful times where “cost is not a factor”.

- TempDB and Runtime Effects Expanding

Database StoragebenefitsTempDB, reducing interruptions fromRuntime Autogrowth(a Pro). But larger databases also increaseSQL Server Startup Timeafter a reboot (a Con). These are the hidden transferences of cost that often escape simple performance dashboards.

Each arrow in the TOSN (particularly the TO side) could be statistically validated, by checking correlations or regressions between metrics over time—but those relationships aren’t absolute. This is actually part of the Tuple Correlation Web.

Relationships in Context

I don’t need to do any research to figure out that the two most common answers to a question are “I don’t know” and “It depends”. Even though there is a general relationship, relationships are an “it depends” concept.

While building the “SQL Server Performance Tuning Web” (let’s call it SSTOSN), it was quickly evident that the effects a configuration setting and/or metric had on each other were quite “it depends”.

For metric values, what is a good and bad metric depends on what we intend. High CPU is fine if that’s what we expected.

The graph structure of the TOSN wasn’t good at expressing conditions. It was great at expressing relationships, but there are always exceptions. There is the mammal with beak (platypus). Although the first thing I think of with birds is they fly, many birds cannot fly. Relationships of all sorts change at various scale.

To include all of those exceptions that in a graph would make it even more unwieldy than it actually is. By abstracting exceptions out, the graph can express generally what happens. Applying exceptions is the application of rules, which is what Prolog does very well.

Prolog had four main roles in the TOSN:

- As mentioned, determine the strength of relationships between configuration settings and/or metrics. This is the knowledge of an expert, such as a doctor.

- Determine what metrics are in pain. This is like describing your symptoms to a doctor.

- Determine which configuration settings seemed odd. This is like a doctor asking for your current medications, examination observations.

- Set the parameters of each relationship on the trade-off side.

The Process

Before a discussion on the art and science of authoring Prolog, let’s look at the nature of the Prolog we will need and how it will be used. These are the main use cases for Prolog in the TOSN:

- Configuration settings are collected and converted into a context Prolog snippet of facts. This will be referenced by the other Prolog by importing it.

- SQL Server and Windows metrics are captured over a set period of time—for example, a 3-hour period. These metrics are loaded into a data mart.

- KPI metrics (status, value, trend, target/goal) are collected and loaded. This could be authored as a Prolog

- The strength of relationships, based on the current context, are calculated using Prolog.

The first three items could be considered as “global variables” for the SQL Server installation we’re working on. Following an examples of what they look like, beginning with #1, Configurations settings.

/* ———————————————–

Configuration Settings — State, Value, Range, Impact

———————————————– */

% config(Name, State, Value, Range, Impact).

config(maxdop, active, 8, range(1,16), query_parallelism).

config(max_server_memory, active, 32768, range(8192,65536), buffer_cache).

config(create_nci, applied, count(42), range(0,inf), table_scans).

config(tempdb_files, active, 8, range(4,12), io_contention).

config(runtime_autogrowth, enabled, yes, boolean, storage_latency).

config(cpu_capacity, provisioned, 16, range(8,32), query_throughput).

config(database_storage, provisioned, 2000, range(500,5000), tempdb_growth).

config(auto_create_stats, enabled, yes, boolean, query_estimation).

config(fill_factor, set, 90, range(70,100), fragmentation).

Code 1 – Configuration settings.

Code 2 shows examples of Windows and SQL Server PerfMon counters (#2 above).

% === Windows Performance Counters

% counter(Name, Category, Unit, Desc).

counter(‘Processor(_Total)\% Processor Time’, windows_cpu, percent,

‘Overall CPU utilization across all cores’).

counter(‘Memory\Available MBytes’, windows_memory, mbytes,

‘Amount of physical memory available for allocation’).

counter(‘LogicalDisk(_Total)\Avg. Disk sec/Read’, windows_disk, seconds,

‘Average time per read operation across all logical disks’).

% === SQL Server Counters

counter(‘SQLServer:Buffer Manager\Buffer cache hit ratio’, sql_buffer, percent,

‘Percentage of pages found in buffer cache without disk reads’).

counter(‘SQLServer:SQL Statistics\Batch Requests/sec’, sql_exec, per_sec,

‘Number of Transact-SQL batch requests received per second’).

counter(‘SQLServer:Access Methods\Full Scans/sec’, sql_access, per_sec,

‘Number of unrestricted full table or index scans per second’).

Code 2 – Windows and SQL Server PerfMon counters.

Code 3 is an example of a Prolog for the KPI metrics (#3 above):

/* ———————————————–

KPI Metrics — Status, Trend, Value, Target

———————————————– */

% kpi(Name, Status, Trend, Value, Target).

kpi(cost, warning, up, 8500, 7000). % USD/month

kpi(cpu_utilization, poor, up, 82, 65). % percent

kpi(reads_per_query, poor, steady, 4500, 2000). % pages/query

kpi(cpu_capacity, good, steady, 96, 90). % percent available

kpi(tempdb, good, down, 70, 80). % utilization percent

kpi(database_storage, warning, up, 92, 75). % percent used

kpi(ss_startup_time, good, steady, 40, 60). % seconds

kpi(runtime_autogrowth, poor, up, 8, 2). % events/day

Code 3 – Prolog snippet defining the SQL Server KPIs.

Figure 4 is a diagram of the process for prepping the TOSN for a context. On the left is a typical BI system of users, a visualization tool (Tableau), and a SQL Server database running on a Windows server. On the right is an extremely small segment of a TOSN.

Reading Figure 4:

- This represents a typical SQL Server enterprise installation. It’s installed on a Windows Server. It also shows icons for SQL Server Profiler and Performance Monitor. These should be run concurrently for a few hours to capture data needed to troubleshoot a performance problem.

- These are the BI users using Tableau. They are the ones who reported slow queries.

- There are four work flows capturing data and converting into Prolog. Each work flow consists of code to collect data from a source (SQL Server, Windows, PerMon), dumping the data into a CSV file, and a function that converts the data into Prolog.

- The end product Prolog of the four work flows will be referenced by relationship Prolog within the TOSN (see Figure 5 below).

- Items 5-9 involve setting values for nodes and relationships. This item (5) retrieves the Logical Read / Second metric from the SQL Server Perfmon counter.

- This is the total capacity of the CPUs—across all cores.

- SQL Server configuration that assigns a number of CPU cores to SQL Server.

- CPU percentage utilization across all cores.

- Prolog that sets properties of the relationship between Create NCI and the Table Scans metric. We’ll dive deeper into this later. Note that Create NCI is a configuration. I’ve taken the liberty to consider indexes as part of configuration.

Authoring Prolog

At my first demo of the SSTOSN (Dec 2005), someone asked me how I got the rules. He said that he had worked on a Prolog project back in the 1980s and it was impractical to author, to put it lightly. I didn’t deny it at all! It was even harder to maintain.

The demo was around the time of the release of SQL Server 2005. But I created the SSTOSN on SQL Server 2000 (the vast majority of the customers were still on SQL Server 2000). I was painfully aware that maintaining/updating the SSTOSN to accommodate both 2000 and 2005 was even harder than originally authoring for 2000.

When I began creating the SSTOSN, I reasoned that authoring that KG would require about as much intellectual effort as writing a book. After having recently written two books, I now see the how naive I was. As daunting as writing those books were to write, authoring the SSTOSN was much harder. In some ways, it’s like trying to write a graduate level text that the typical 5th grader could understand. Also, English is my native language, whereas RDF/OWL is not. Most spoken languages are more expressive than RDF/OWL. There is more to communication than subject-verb-object triples.

Automatic Rule Generation

In Part 4 of Prolog in the LLM Era series, I address how machine-learning (non-LLM, non-neural networks) can be a powerful source of automatically generated Prolog rules.

Modern stacks can auto-author Prolog in two ways. First, give an LLM a clean, plain-language specification (“if X and Y then Z—otherwise W”) plus the predicate schema, and have it emit audited Prolog clauses; this leverages the LLM for drafting while keeping decision logic in a deterministic rules engine. Second, convert interpretable ML models into Prolog directly: extract rules from decision trees/association rules or export algebraic models (logit/linear) and compile them to predicates; workflows that start from a pickle or PMML artifact can traverse the model structure and serialize equivalent Prolog rules for transparent, testable reasoning.

This “ML-to-Prolog” route has been demonstrated with tree models (e.g., Iris → rules) and complements the LLM-assisted authoring path by grounding rules in learned heuristics that can still be inspected, versioned, and mixed with hand-written logic.

ChatGPT and Grok are pretty good at generating and understanding Prolog (I haven’t tried other LLMs). But like using the LLMs for coding with languages such as Python and Java, it has room for improvement. And of course, I expect these capabilities to improve quickly.

Even LLMs Don’t Know What They Don’t Know

I mentioned earlier that I wish ChatGPT was around back in 2005 to assist me with authoring the SSTOSN. However, I also mentioned that there wasn’t nearly as much training material for ChatGPT back in 2005. That is, material authored by human experts, the intelligence fodder for LLMs.

As mentioned earlier, there have been very many great books, articles, and stackoverflow material on SQL Server 2000 that didn’t exist back in 2005 to train an LLM. With all that high-quality material available today, LLMs can indeed reduce to weeks what took months back in 2005. However, I need to point out that in 2005, there was still a fair amount of material on SQL Server 2000, since it had been out for almost five years by then. So had LLM technology existed back then, it still would have been able to help with the SSTOSN.

An LLM may seem universal, but it only knows what it has been exposed to. It has no internal concept of your codebase, your data schemas, or your architecture. Ask it to build a TOSN for a private, proprietary system, and the LLM will do what it always does—attempt to formulate a good guess from other domains, which we call hallucinations. It can’t reason about relationships, metrics, or failure modes that were never in its training set.

In short: the LLMs of today don‘t know what they don’t know. In all fairness to LLMs, many of their attempts at creativity are taken as hallucinations. Not all hallucinations are attempts at creativity, but a subset that are no different from fresh human-generated ideas.

So what do we do about building a TOSN for subjects that are unknown to the general public, therefore unknown to public LLMs? Let’s use my Reps software I described in Reptile Intelligence as an example. An LLM doesn’t know anything about the internal workings of Reps—for the moment, only I do. It can take a bunch of very educated guesses based on my description of what it does. So, out of the box, a public LLM such as ChatGPT isn’t able to help me write a TOSN for Reps. However:

- I could fine-tune a foundation LLM with my log notes on Reps, its actual code, telemetry artifacts, and test scripts.

- Train a “Reps Expert” as a small language model (SLM) with that material listed in the prior item that operates with a Mixture of Experts system.

- Have the LLM assist with writing about the parts it knows about, such as the environment within which I implement Reps.

- It’s loaded on a cluster of typical servers, which is very publicly familiar.

- It’s currently a .NET application, so knowledge of the .NET runtime is relevant.

- Reps is primarily about non-deterministic finite automata (NFA), which is a level of the Theory of Computation.

Every new system lives inside an ecosystem of older ones—operating systems, databases, network protocols, data centers. Here, the LLM is invaluable. It already understands how those adjacent components behave, how to connect to them, and how to script or query them. It can scaffold the glue, design interfaces, and even document integration logic faster than any human team.

But inside a proprietary boundary, the model is blind. That’s where we introduce Small Language Models (SLM)—a lightweight companion trained or embedded on the code, notes, telemetry, and documentation. The SLM becomes the local expert, aware of a domain’s objects and causal rules. Paired with a general LLM, it forms a miniature cognitive mesh (a fairly recent buzzword): the LLM handles the world outside, the SLM understands the world within, and together they can finally reason across both.

With the help of today’s level of AI, the ability to engage current data sources, the task of authoring a comprehensive KG is much easier—as long as the knowledge is already well-known. Today’s AI is not smart enough to help us with new concepts. The hope is that at the level of a future AGI, it can grasp new concepts (concepts for which there isn’t any training material).

Code vs. Knowledge Graph

Getting back to a KG, isn’t the code (in this case, the hefty amount of C# code that comprises Reps) about as fully explicit in expressing a subject as there can be? Couldn’t LLMs reference the code and thus there isn’t a need for a knowledge graph representation?

Remember, the reason for a KG versus an LLM is that we (humans) have full control over what it is. But that’s the case with code as well. Code is completely transparent to us (as long as we trust the compiler, runtime, and operating system).

As an intermediate guitar player—without perfect pitch, average relative pitch, not much creative musical instinct—I appreciate the need for songs in the form of a recording, tablature, lyrics, and the many tutorial videos of a particular song. If I were Tommy Emmanuel, I only need to hear a recording or even just humming of a tune to play it. If I were a middle-of-the-pack professional, I might need to reference a tablature for something I can’t quite figure out. But even Tommy Emmanuel might occasionally need to reference a lyrics sheet.

For me, I need to hear the song played over and over, then I use the tablature to figure out the notes. Although, as I become more proficient, the need for the tablature diminishes—as it would be for an AI requiring any supporting material as it becomes more intelligent.

The difference between computer code and music is that for code, there isn’t any room for interpretation. Music invites expression, phrasing, timing, tone, touch—the performer inevitably adds themselves to it. Code does not. Code is an explicit, literal specification of how the system behaves. There’s no ambiguity, no stylistic wiggle-room, no “maybe the system meant this instead”. It is already the ground-truth representation of the logic.

And that’s where the contrast with a KG takes form. A KG doesn’t replace the explicit logic of code. It’s meant to expose the structure of knowledge—entities, relationships, constraints—in a form that is inspectable, queryable, and rearrangeable without digging through thousands of lines of implementation. Code expresses how things work; a KG expresses what things are and how they relate. Code is a machine-level commitment. A KG is a human-level explanation.

So while an LLM could ingest the source code of Reps and “understand” it statistically, that doesn’t give us the same affordances as a KG. Humans don’t want to mentally traverse a million-line codebase to see the relationships between states, transitions, events, and constraints. A KG gives us the abstraction layer that sits above code—something closer to tablature or a chord chart. It’s not the performance, and it’s not the recording; it’s the conceptual map that helps you work with the system at a higher level.

Code is the exact execution, the KG is the explicit structure, and the LLM is the interpretive assistant. They occupy different layers of understanding.

Knowledge Graphs vs. Prolog

I earlier asked, “If LLMs are so great, why do we need KGs?” Here we explore the question, “If KGs are so great why do we need Prolog?” To be clear, why not write the TOSN with just KG (thus removing the need for Prolog)? I addressed that comprehensively in Part 7 of the Prolog in the LLM Era series, where I describe the differences between Prolog and Knowledge Graphs.

Prolog and KGs both describe relationships between things, but they answer different kinds of questions. A KG is great for tracing relationships. For example, “what connects to what?” It shows how entities, classes, and properties form a semantic network. It’s spatial and visual—ideal for people who think in diagrams, hierarchies, and maps of meaning. However, when we surpass a few dozen nodes, it’s not readable as say a higher level view of a map. It becomes more akin to looking at the whole world in one map.

Prolog, on the other hand, is built for computing relationships. For example, “Given these conditions, what must be true?” It’s procedural logic expressed declaratively: you tell Prolog what you know and what you want, and it deduces what follows. Where a knowledge graph helps you see relationships, Prolog helps you reason through them.

Theoretically, you could encode one in the other. Removal of a redundant moving part is mostly a good thing. A Prolog fact could become a triple, and a triple store could represent logical predicates. For the latter, the ontological predicates would be like what is shown in Table Z.

| Predicate (Prolog) | Equivalent Ontological Meaning | Example Usage |

|---|---|---|

is_a/2 | Class or taxonomy membership (rdf:type, rdfs:subClassOf) | is_a(dog, mammal). → Dog is a Mammal |

instance_of/2 | Entity → class relationship | instance_of(fido, dog). |

part_of/2 | Part–whole (mereological) relation | part_of(engine, car). |

has_property/2 | Attribute/value pair | has_property(engine, horsepower(250)). |

connected_to/2 | Relational or associative link | connected_to(database, api_gateway). |

equivalent_to/2 | Semantic equivalence (owl:sameAs) | equivalent_to(h2o, water). |

causes/2 | Causal or influence relation | causes(overheating, shutdown). |

depends_on/2 | Dependency or prerequisite | depends_on(application, database). |

located_in/2 | Spatial or contextual containment | located_in(server1, datacenter_a). |

related_to/2 | Generic fallback for any unspecified relation | related_to(cpu_utilization, temperature). |

has_subclass/2 | Inverse of is_a (taxonomy navigation) | has_subclass(mammal, dog). |

uses/2 | Functional relationship | uses(service_a, library_b). |

produces/2 | Output or generation relationship | produces(factory, widget). |

has_role/2 | Role assignment | has_role(eugene, author). |

But practically, it’s far easier to express Boolean and conditional logic in Prolog than to express logic over relationships as a graph. If I had to choose, I’d choose Prolog — it’s the reasoning engine that can compute over the same data the knowledge graph visualizes.

KG at the Higher Level, Prolog as the Exceptions

KG are more akin to schemas and headers, whereas Prolog is more of an “executable” coding language. The really neat thing about Prolog is that the rules, data, and query language are pretty much the same thing.

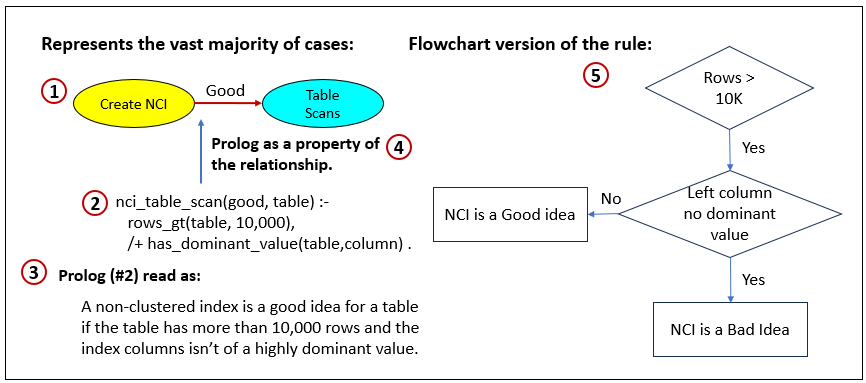

Let’s look at an example of a rule from the TOSN sample in Figure 3 and Figure 4. Specifically, Figure 5 is a closeup of the relationship between the nodes, “Create NCI (Non-Clustered Index” and “Table Scans”. The main relationship is that an NCI reduces the need to scan through an entire table at query time by being able to home in directly to the specific rows of interest. That’s usually the case, but not always. Here are two reasons:

- If the rows of the index are mostly of a dominant value, the result is that searches for that dominant value isn’t that helpful. For example, a list of football fans in Boston is likely dominated by men who declare the Patriots as their favorite NFL team. So an NCI created to aid in searching that database for male Patriot fans probably won’t be of much overall help.

- If there are just a few rows, it’s less compute-intensive to just scan through the entire table avoiding the overhead of using the NCI.

Here are descriptions for the items in Figure 5:

- The relationship declaring that creating NCIs reduces table scans for a SQL run in SQL Server.

- A Prolog defining the exception to that rule expressed in #1.

- Text describing the rule (#2).

- Just being clear about where the Prolog expressed in #2 applies in the KG.

- A flow chart version of the rule.

Regarding item 5, the reason I used a flow chart is because it is a graph representation that could readily fit into a knowledge graph. But imagine one to four of these added to KG. It would be many times harder to navigate. But more importantly, the graph form lacks the capabilities of a programming language. This could have been Python as well—or SWRL, which we’ll cover soon.

I need to admit that I took a couple of short cuts here. The Prolog (2) itself isn’t really a description of how and why this Prolog rule is an exception. I do explain that in item 3. So we could include it in the authored Prolog file in a header of metadata embedded in the Prolog file as a multi-line comment, as shown in Code 4.

/*

Author: Eugene Asahara

Description: A non-clustered index is a good idea for a table if the table has more than 10,000 rows and the index columns isn’t of a highly dominant value.

Created: 2025-11-19

Last Updated: 2025-11-19

*/

nci_table_scan(good, table) :-

rows_gt(table, 10,000),

/+ has_dominant_value(table,column) .

Code 4 – Prolog and metadata for determining is non-clustered index is a good idea.

But even that isn’t really an adequate description—that is, for a novice database engineer using the TOSN. That metadata header could be included in a prompt to ChatGPT for a comprehensive explanation. I submitted the prompt below to ChatGPT 5.1:

Could you provide a comprehensive explanation for the why and how expressed in this Prolog? Assume I’m a novice at the subject:

/*

Author: Eugene Asahara

Description: A non-clustered index is a good idea for a table if the table has more than 10,000 rows and the index columns isn’t of a highly dominant value.

Created: 2025-11-19

Last Updated: 2025-11-19

*/

nci_table_scan(good, table) :-

rows_gt(table, 10,000),

/+ has_dominant_value(table,column) .

ChatGPT’s response can be viewed on the GitHub repository. It’s a little big to include here.

However, remember that ChatGPT will be able to provide a comprehensive explanation only because it’s already trained with tons of material related to SQL Server. It won’t be able to do that for new systems, for example, the Reps software I mentioned earlier.

Lastly, note the “Created” and “Last Updated” metadata. I included that to be used for deductive time travel. That is, keep a history of Prolog rules so we have a record of how decisions were made in the past.

Prolog vs. SPARQL/SHACL/SWRL

The KG aspects of the TOSN capture structure while the Prolog aspect and graph query capabilities are about behavior. However, Prolog could be seen as both, representing rules and as actionable code.

A reasoning engine — such as SPARQL, SHACL rules, or SWRL — would need to interpret these relationships to produce the same result as Prolog.

That said, at least for now, they’re complementary. KG show what’s connected and Prolog decides what’s true. And if we ever want to visualize a Prolog program, it can easily unfold into its own graph-shaped ontology or taxonomy—the same underlying knowledge, just seen from a different angle.

At least for now, the graph database world has for more scalable platforms than Prolog. So for scalability, my suggestion is to author as much on the KG side as possible.

Recursion is sometimes the scary part of Prolog. But it is the power. Intelligence is parallel and highly nested.

The Forms of Human Knowledge

In the context of this blog, there are four forms of human knowledge:

- The collective knowledge in all our brains.

- The knowledge we’ve expressed (from #1)—in the form of books, articles (text, video), interviews (audio, video, text).

- LLMs trained with #2—a fully integrated compilation of our collective corpus of knowledge.

- A fully integrated knowledge graph, created mostly by #1, but #3 today as well. There exist a few that were painstakingly created. Wikidata, Google.

The trouble with #2 is that no one human has the capacity to digest all the material, so knowledge is fragmented. It can exist in countless combinations of pieces of knowledge distributed among the eight billion of us, but each person only knows a small fraction.

An LLM (#3) has its problems. For example, it hallucinates, it has a tough time when working on what isn’t in its training material, and it’s mind-bogglingly expensive to create and query. To me, the biggest problem with #3 is we don’t have direct control over how it processes stimuli (reactive queries we submit, or proactive queries it conjures up just like we conjure up thoughts).

That is precisely the benefit of #4, a fully integrated knowledge graph. As mentioned earlier, KGs are fully transparent, whereas LLMs are black boxes. KGs are normally readily understandable as they are readily understandable symbols—usually in the form of node and relationship labels in a spoken language.

KGs can be a source of dreaded information overload, which is a kind of imperfect information. For example, my SSTOSN quickly became a terrible maze. But I could deterministically query it with query algorithms, with a response and a trace I could examine.

What I’m saying in this topic is that KGs are our human-validated overseer in the arena of AI. If there is a question of, “Do we still need KGs in the world of LLMs?”, yes, it’s our transparent, explicit statement of how we see things and what’s important to us.

Authoring KGs is “coding”, but not as esoteric as programming code (like C++, Java, Python). The reason a KG is easier is because it’s a subset of what full coding require—control flow, functions, OOP, etc. Yes, it’s part coding, but much more generally philosophical—which is fundamentally pertinent to us as sentient beings. Maybe the best final exam for any course is a KG instead of a written thesis.

Vibe Coding: Prolog + TOSN = CTG

As a reminder, TOSN is the name I used back in 2004 and that I used that name throughout this blog because it was used as the example. But from here, I’d like to call it “Conditional TradeOff Graphs” (CTG), again, to better highlight Prolog’s role.

One of the major buzzwords to have emerged from the LLM Era of AI is “vibe coding”. It’s a style of creating systems where we’re no longer hand-authoring every line of logic, but also not surrendering everything to a black-box LLM. Instead, we describe the vibe of what we want. In the context of this blog, it’s the trade-offs, the “it depends”, the constraints we care about, and let AI help draft the concrete rules (Prolog) and structures (the semantic network side)—while we keep final say and full traceability.

Usually, vibe coding today means having an LLM spit out Python or JavaScript, but in this blog I’m pointing that same instinct at the CTG instead. In fact, in some ways, Prolog is an even better candidate for vibe coding because expressing intent as Boolean logic and rules is far more direct than the procedural scaffolding it takes to write Python or JavaScript.

Today’s LLMs are fantastic at this “vibe” layer. I’ve mentioned a few times that what took me months in 2005 would probably take me weeks with LLM assistance—almost a magnitude better. For example, if I say, “When CPU is high and reads/query are poor, consider adding a nonclustered index—but not if the table is tiny or super skewed”, that’s enough for a model to sketch out Prolog, SPARQL, or pseudo-code. It’s not inventing the intent, just helping serialize intent into executable form. The problem is that LLMs themselves are not directly controllable. We can shape prompts, add retrieval, add guardrails, but we can’t see or govern the internal machinery the way we can a Prolog file or a TOSN diagram.

The CTG is, in a sense, my platform for vibe coding. I don’t really want to write every rule from scratch, but I still want each rule to be deterministic, inspectable, and debuggable. So the workflow becomes:

- Think and speak in vibes: “Cost cannot go up, latency must go down, CPU is already hot, storage is cheap, tempdb is thrashing”.

- Let the LLM draft: Have the LLM propose candidate Prolog clauses and TOSN link adjustments that reflect those trade-offs.

- Pin it down in Prolog: Review, test, and refine those rules until they behave the way I intend, with explicit conditions and exceptions.

- Attach them to the graph: Wire those rules into the TOSN so each edge has both a structural meaning and a soft-coded, testable behavior.

In that sense, Prolog is not just “another logic language” but the execution layer for vibe-coded intent. The TOSN gives us the structural canvas of trade-offs; Prolog supplies the precise, executable “if X and Y then maybe Z, unless W” logic, and the LLM plays the role of very fast junior author, turning my vague, verbal “this is the kind of thing we’d do in this situation” into candidate rules and metadata.

This is also how I square my skepticism about pure symbolic systems with my discomfort around pure LLM systems. Purely symbolic approaches are brittle, pure LLM approaches are powerful but opaque and only indirectly steerable. A vibe-coding workflow over TOSN + Prolog sits in the Goldilocks middle where probabilities and context can live in the rules and metrics, structure lives in the graph, and the noisy, fat-tailed richness of human description is handled by an LLM that proposes, rather than silently decides. We still end up with something we can reason about, test, and audit.

The notion of Knowledge Graph + LLM is actually a big part of my book, Enterprise Intelligence. But now it can be called a form of vibe coding.

The Four Roles Behind a Real CTG Project

When I built the original SQL Server TOSN back in 2005, I was operating as the entire team—domain expert, data engineer, ontologist, and Prolog author rolled into one. That’s was possible because I knew the SQL Server domain, could code, and had experience with Prolog and knowledge graphs.

Most of the time, though, a proper CTG requires at least four distinct roles, each covering a different form of knowledge:

- Domain Expert The person who actually knows how the system behaves: the edge cases, the trade-offs, the “it depends,” and the failure patterns. They define what matters.

- Ontologist (Semantic Web Engineer) This forms the SN side of the TOSN — the “what exists” part. Works with the domain expert to structure the world:

- What are the entities?

- What are their types?

- What belongs where in the ontology or taxonomy?

- Prolog Author / Knowledge Engineer This becomes the TO side’s rule layer — the “when is it true?” part. Works with the domain expert to capture the conditional logic:

- When does this relationship hold?

- When does it weaken or reverse?

- What are the exceptions?

- Data Engineer Procure and wrangle disparate and possibly massive volumes of data. Handles the telemetry: metrics, counters, configurations, events, KPIs. They ensure the system has the observational data needed to activate the rules and relationships.

Together, these four roles create the CTG:

- Domain expert + ontologist → the semantic network

- Domain expert + Prolog engineer → the conditional trade-off logic

- Data engineer → the real-world signals that drive the reasoning

This isn’t unlike data science projects that require:

- The data scientist who knows the math, algorithms, and scientific methodology.

- Data engineer who can procure and wrangle disparate and possibly massive volumes of data.

- Domain expert who knows what must be done, the problem to solve, whether it has been solved, and is often a major stakeholder.

Conclusion

The world in which we live is complex. That means it’s made up of countless agents all with minds of their own. Some of those agents such as humans are mostly complex. Some are simple or even complicated with mechanistic minds rendering their actions predictable. But interactions between agents—simple, complicated, and complex—are virtually unpredictable. Add to that the properties of these agents and the webs of relationships are constantly changing.

Our human intelligence evolved to embrace the complexity of this world. Instead of following “best practices” developed and handed down through evolution, like non-human creatures, we’re able to play “what-if”. We’re sapient.

However, applying our sapient superpower in this complex world isn’t a matter of question and answer or decide and act. Our quests are an iterative process. It means that to satisfy our needs/goals, we can only start out with a best guess. That best guess should involve mitigation of known risks so that should it fail, we can survive for Plan B. For each iteration, we take a best guess, execute on it, analyze the result, learn from mistakes, and repeat.

Once we get it down to one iteration, it’s time to automate that process. That means we create machines, processes, and principles that reduce complexity down to the level of complicated or even simple. The tricky part with these machines is in how they interact with other machines and how we protect them from the outside world that wears them down. We address those issues with explicit interfaces and defensive systems, respectively.

As long as those machines work well and outside forces don’t successfully destroy them, the machines capitalize on a shortcut we discovered between Point A and Point B. That is, until the complexity of the world fades away the conditions that made that hack work.

The reason for bringing all that up is to remember the development and application of the simple and complicated is really the domain of humans (at least for now). But before we can pull off the tricks of creating simple and complicated machines within the complex world, we need to develop within us a model of our world.

World Model Training to Symbolic Thinking

The day after I began writing this blog (Nov 11, 2025), Yann LeCun announced he would be leaving Meta, presumably to found a startup on his “world model” framework known as JEPA (Joint Embedding Predictive Architecture).

Yann LeCun’s concept of “world models” in AI refers to the idea that intelligent machines need to build internal maps or simulations of the real world to truly understand and interact with it, much like how humans learn by observing, predicting, and experimenting with our surroundings. Instead of relying solely on vast amounts of text data like today’s chatbots, LeCun envisions AI systems that create these dynamic mental pictures—predicting what happens next in a scene, grasping cause-and-effect in physical spaces, and learning from trial-and-error actions.

This approach, often powered by energy-based learning where the AI minimizes “surprises” in its predictions, aims to make machines more robust, efficient, and capable of handling real-life tasks, like a robot navigating a cluttered room or a self-driving car anticipating obstacles, paving the way toward more human-like artificial general intelligence.

At the time of writing, I haven’t yet dived deeply into JEPA, but I see it as part of a stack that follows this human analogy:

- As infants, born with a sort of “blank slate” (no language, just raw sensory), we build a model of the world in our brains through just observation (involving all of our senses). Results and feedback are pretty much instantaneous, making cause and effect likely, and it’s quickly back-propagated, adjusting our developing world model.

- Eventually, the world model evolves the ability to speak and read. This is the ability to emit our thoughts and feelings, as well as consume spoken information from others, in a symbolic manner understood by those around us.

- With that ability, we’re able to consume existing knowledge through listening to parents and teachers and reading written knowledge. It’s all communicated through the ability speak and read. However, we our “world models” continue to learn through sensory.

- At some point, we hopefully add to the corpus, creating new things and communicate them to others through speech and/or another method of encoding.

Item 1 sounds like Yann LeCun’s world model. Of course, it’s not as simple as that, but at least at a high-level. Item 2 sounds like the transformer architecture. Item 3 sounds like the process of an LLM ingesting the corpus of written human knowledge.

The model of the world as described in Item 1 isn’t enough for creativity. Nor is Item 2/3—since LLMs still struggle when I ask about something novel. It seems like both are required. In fact, even after we’ve developed the ability to speak (2), we still learn through observation as well.

LLMs more than just “next-generation autocomplete”, as ChatGPT earlier said. They’re our best current engine for artificial analogy and symbolic manipulation. They live in the space of language, code, and concepts—where ideas can be compared, blended, reframed, and composed.

In contrast, “world-model” approaches like JEPA are about mimic learning, watching the world unfold (video, sensor streams, interactions) and learning how states evolve over time. Those systems learn the physics of experience while LLMs learn the semantics of description. We need both the world models that ground intelligence in how reality behaves and language models to reason about that reality using symbols, analogies, and abstractions that humans can work with.

The CTG is a methodology for the serialized abstraction of “world models”. For my SQL Server example, it is the serialized abstraction of the “physics of SQL Server”. A CTG is not nearly as comprehensive as the actual SQL Server running on an actual Windows OS on an actual server. But it’s enough of a reasonable facsimile towards the purpose of exploring a space of possibility.

The sensory experiences and ingestion of what we learn through the spoken or written words and observation of others create a structure that addresses complexity. The world models of Yann LeCun and the digestion of the transformer architecture into LLMs are the “artificial” counterpart—kind of like a business counterpart to Feynman Diagrams in physics (which was my initial inspiration).

From that point of view, although the notion of mapping systems in the CTG framework sounds like a case of, “Are you crazy?! Who would ever do that?! Do you know how hard that is?!”, there are profound benefits. The first is what I already mentioned about CTGs being a deterministic, transparent, traceable representation of our systems. Two other profound benefits are related to all the fear of “AI taking all of our jobs” and the fear of “losing our critical thinking capacity”. I suggest that building CTGs is a skill that addresses all three.

Even as world models and LLMs advance, the ability to explicitly map how a system works—its components, its forces, its trade-offs—is a deeply human skill that machines should complement, not replace. Building a CTG is deliberate thinking in the spirit of complementary human/machine intelligence. It requires understanding ambiguity, surfacing hidden assumptions, spotting the “it depends”, and turning muddled expertise into something transparent and traceable. These are precisely the mental habits people fear AI will erode.

Authoring and utilization of CTGs strengthens the abilities we must preserve—systems thinking, modeling, explanation, judgment. It keeps us in the loop not as button-pushers, but as architects of how intelligence, artificial or human, should behave.