In the conclusion of my last blog, Chains of Unstable Correlations, I wrote:

When you work around experts long enough, you notice that experts sometimes (usually?) forget what isn’t obvious to non-experts. Conversely, people in the field often see things experts overlook because they live inside the operational texture of the system.

After a conversation with an old friend yesterday, I realized that after my barrage of 45+ minute blogs since the publication of my book, Enterprise Intelligence, in June 2024, it’s time to take a step back and regroup with the two or three readers of my blogs about the bigger picture of the intelligence of a business. We need to fill in all those pieces that can get lost across about 150K words spanning over a year.

It’s like if you watched all seven seasons of “Better Call Saul” in the first run, meaning over the seven long years, not binged. If you did watch it in the first run like me, you know what I mean 😦

I’m a BI Architect/Developer who misunderstood the “I” in BI all those years back in 1998 when I first heard of BI. I had just started my dev position with the SQL Server OLAP Services 7.0 team at Microsoft, and never heard of an OLAP, BI, or DSS. I thought the “I” in BI was like the “I” in AI. I even used “Putting the ‘I’ Back into BI” as my blog site tag line—it still is today.

It wasn’t until about 15 years later that I realized the “I” in BI was like the “I” in CIA—as in, gathering intel to give to the decision makers. I thought the DSS/BI field just got lazy and retreated to an easier definition of intelligence. But I guess it was by design. Subconsciously, I think I didn’t want to see that since the “I” in AI is a lot more fun than the “I” in CIA. So that led me down a long and winding road where I was perpetually out of sync with the mainstream BI crowd and sort of locked out of the AI crowd.

So it’s perfectly understandable that sometimes I need to step back to ensure we’re on the same page. Or at least “on the same book” (in this case, Enterprise Intelligence).

FYI, here is a list of most relevant of those “recent” blogs:

- The Complex Game of Planning: Plans are about how to get from State A to State B. It’s usually not a single step, the map isn’t fully materialized, and the sequence of tasks often requires parallel threads.

- Stories are the Transactional Unit of Human-Level Intelligence: This is the way we passed down knowledge before we could write.

- Beyond Ontologies: OODA Loop Knowledge Graph Structures: This offers a few examples of story formats.

- Conditional Trade-Off Graphs – Prolog in the LLM Era – AI 3rd Anniversary Special: Mapping pros and cons of configuration changes we make. Being cognizant of them, even the ones we’d rather sweep under the rug, is a key to good decisions.

- Long Live LLMs! The Central Knowledge System of Analogy: This defines the roles of LLMs in my framework. That role is of the know-it-all friend who knows a lot about a lot of things. This friend can also organize.

- Reptile Intelligence: An AI Summer for CEP: This is an explanation of System 1 in my framework. A web of functions, each fast, simple, highly-probable but not exact.

- Outside of the Box AI Reasoning with SVMs: The freedom to push the boundaries with some idea of how far we can go before things get scary. This prevents us from needing to be overly-cautious because we don’t know where the “red line” (a boundary we are not supposed to cross) is at. This is really Part 1 of Chains of Unstable Correlations.

- Analogy and Curiosity-Driven Original Thinking: The way we really create.

- Thousands of Senses: Not just the five senses we learned about in school.

This break is especially timely since my next blog, “The Products of System 2”, is indeed intended to rein things in. Originally, what I’m writing here was supposed to be the introduction to my upcoming blog, “The Products of System 2”, but it’s too long for that purpose and I want to be sure I clarify what I have in mind.

So I decided to break out that long intro into a preview: “Intro to The Products of System 2”

The upcoming post, “The Products of System 2”, is like the “third act” (the closing arc in which prior forces converge into outcome) of my virtual book, The Assemblage of AI. It’s not the end of the trail, but the beginning of the end. It just ties up the central question:

What is the actual product of The Assemblage of AI?

It’s the same as the product of human intelligence: stories, plans, procedures, strategies, designs, recipes, checklists—the intellectual artifacts no other creature on Earth comes close to producing. These are the solutions we’ve figured out through our human history, which were:

- Initially seeded by the solutions created through the semi-brute force of nature’s evolution algorithm over hundreds of millions of years of evolution.

- Then observed by us as a library of examples, used as analogy for solutions adapted to our needs.

- And added to our corpus of culture, which has replaced the seeds of invention created by evolution as the primary fountainhead of further intelligence.

From thousands of sensory inputs, through layers of transformation networks, the end result is an organized body of information that forms the floor of the wisdom level of DIKUW (Data → Information → Knowledge → Understanding → Wisdom).

The “Organs” of the Intelligence of a Business

Let’s revisit the premise that has run through everything I’ve written (the books and blogs), through the distorted lens of my misunderstanding of the “I” in BI.

The Assemblage of Artificial Intelligence uses the Intelligence of a Business as its model.

The core insight of my book, Enterprise Intelligence, is that enterprises have been building analytics platforms for decades through a history of new components that correspond—mostly unintentionally—to components of human intelligence. It makes sense: we treat corporations as entities, and human intelligence is the only real model we have. So our analytical platform reflects our thinking process, mimicking the same functional needs. We could say the analytics platforms we’ve been developing are being made in our image.

Over the decades, new “flavors of the year” arrived, each hyped as the next big thing because the previous one fell short in some way. But those flavors weren’t replacements—they were necessary components that got installed, grabbing the spotlight while the former star receded into the background. The hard part was always wiring them into a coherent whole. Evolution handled that wiring for biological intelligence over eons. For us, it’s our own creation—so it’s up to us to do the integration.

I thought about this back in the mid 1990s when the Japanese Fifth Generation Computer Systems (FGCS) project of the 1980s seemed to disappear. I never saw it as a true failure. In my opinion, they underestimated the difficulty of crafting rules at scale, building consensus around them, and maintaining them in a constantly changing world. Symbolic expert systems abstracted concepts in ways that lost the rich contextual details—symbols are inherently lossy, even if the intent was deterministic rather than probabilistic. It hit a roadblock, but the direction wasn’t wrong.

When FGCS was abandoned, it didn’t mean Prolog (or any logic programming) didn’t work. It meant Prolog alone wouldn’t suffice—nor will the Semantic Web alone, nor Big Data alone, nor machine learning alone, nor LLMs alone (that’s the “NoLLM” theme running through The Assemblage of Artificial Intelligence). It’s more about AND (incorporating the new big thing) than OR (replacing what didn’t work with something else from a different angle). The trouble with AND is that means there are more moving parts, more things to worry about. With OR, we can just move on to the next thing to see what happens. Well, of course. The world is made of interacting systems, not things. Yes, human intelligence is complex. We architect systems from components. Intelligence is a system, not a thing.

There’s a big difference between something that didn’t work because it’s only part of the solution and something that plain didn’t work.

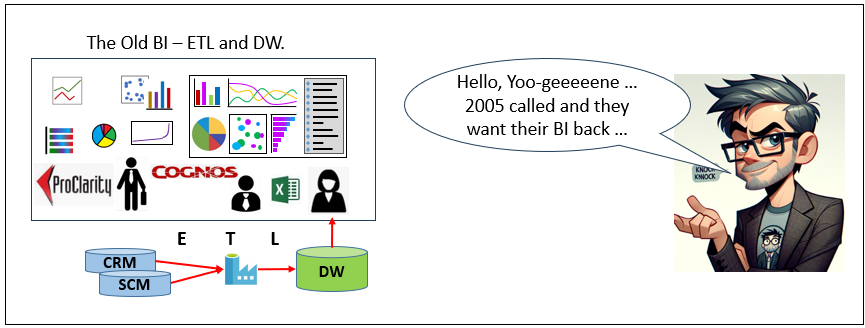

Closer to my heart in the BI world are those OLAP cubes that seem so 2005—a good example of something that was mostly superseded. However, caching when we know something will be used often—and having the power to update it (even if not in real time)—never goes out of style.

BI itself has endured many pains and evolutions from Bill Inmon’s formalization of the Enterprise Data Warehouse long ago, the rise of OLAP cubes, master data management to integrate domains, the shift from ETL to ELT, and the progression of visualization tools from single-user Excel to multi-tiered Power BI.

My Efforts with Prolog (SCL), Knowledge Graphs (Map Rock), and Complex Event Processing (Reps)

In 2004, my work situation led me to build an AI SQL Server performance tuning engineer. (Long story. I wrote about the origin story of my AI journey in Enterprise Intelligence, Intuition for this Book, page 51. I used Prolog, but needed to write my own .NET version (I worked at Microsoft at the time) because I needed to create a codebase I could modify to what were modern concepts at the time, beginning with two key changes.

First, for non-CS types who wrote “code” back then (ex. VBA for Office, R, SQL, and yes, Prolog), it tended to be monolithic, not nicely OOP—hard to write and maintain. I made Prolog highly distributed, snippets of Prolog fragments composed into larger ones, modular logic blocks.

Second, automatic rule generation. Machine learning was emerging, and deployed models were already autonomously making business decisions. Software code was another source. Between those, plus pulling “MetaRules” from SQL queries (reference tables as MetaFacts), rule creation became at least partially automated. But roadblocks remained: managing definitions was brutal, Semantic Web was barely known, no graph databases existed. I couldn’t develop all that as I was writing the Prolog engine and building a data warehouse supporting automatic rule generation and maintenance (what was like MLFlow today).

Over the next decade and a half, those roadblocks dissolved one by one. More data science tools, massive data volumes and cloud infrastructure, master data management, Data Vault, Data Mesh, data virtualization—all arrived as pieces. Integration stayed tough; some even introduced new issues (Data Mesh risking silos, Data Vault slowing queries, MDM needing smarter matching when NLP wasn’t mature enough for complex entities). Semantic Web and knowledge graphs gained traction, and graph databases like Neo4j became practical.

But through my experience with BI, SCL, Map Rock, and Reps, I didn’t need to try my hand at AI again because I knew there were remaining roadblocks.

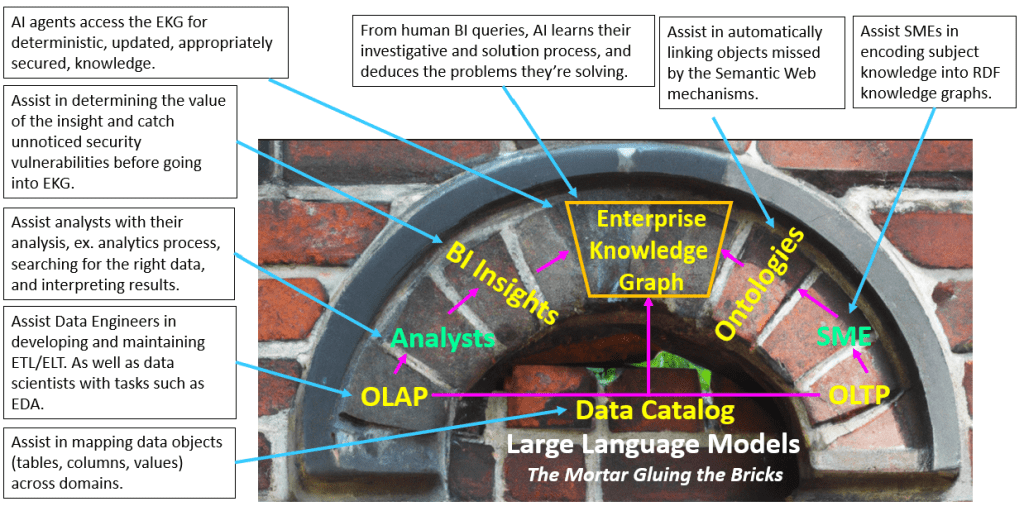

Then ChatGPT went viral in November 2022, and we finally had a major missing piece, LLMs good enough to provide light inference and act as glue between components. For the first time in a decade, I didn’t sense any readily visible big obstacles for my plan. Of course, more obstacles are out there and things still could be better, but the path seemed clear for “good enough” until the next roadblock.

With LLMs (even back in the GPT 3 days), now was broken a powerful barrier to authoring customer knowledge graphs, in a symbiotic relationship between LLMs and KGs. That same concept could apply towards building powerful logic artifacts such as Prolog and strategy maps.

Note: Since a primary theme of Enterprise Intelligence is that LLMs are incredibly helpful towards authoring many types of artifacts (ex. Prolog, knowledge graphs strategy maps, plans, as well as master data management), I need to explicitly address sending prompts describing that sensitive information during that authoring process. Please see this topic addressed in Should We Use a Private LLM?

My book, Enterprise Intelligence, was about exactly that: integrating these disparate pieces (BI, data mesh, knowledge graphs, knowledge workers, AI) into a whole. See my blog, Enterprise Intelligence: Integrating BI, Data Mesh, Knowledge Graphs, and AI

LLMs became the mortar. Why are LLMs good as mortar? They are high-end translators that can serialize and deserialize communication between loosely-coupled or even decoupled components. When we’re having a conversation with someone, we don’t emit some encoding of the trillions of synapses in our brain. We serialize it into language and the friend we’re conversing with deserializes it and hopefully it properly links itself into his synapses. Like a high-end translator LLMs can take into account fuzziness and language nuances. They may not be fluent in the subject of the conversation, but they’re more than just a word-mapper.

Yes, Assembly is Required

To be clear, my approach to AI, at this point, doesn’t require great technological leaps to set up a baseline. It’s data-driven at the foundation and LLM-driven for the glue. We don’t need to invent massive new swaths of tech. What enterprises have already built—data warehousing, business intelligence, OLAP cubes, big data, data science, cloud SaaS platforms, event processing, master data management, data virtualization, methodologies like Data Mesh and Agile project management, ETL/ELT processes, MLflow, semantic layers—is like assembling the organs of an intelligence of a business.

I once read somewhere (I can’t recall where, I was probably dreaming it) that anatomically modern humans of 100,000 years ago were physically like us today. But they didn’t act like us. How those conclusions were made or even how valid that is, I don’t know. But the interesting hypothesis I read of how we could look the same but not act the same is that there was continued tweaking of our neurotransmitters. I don’t know how much truth there is to that. Whether I’m hallucinating having read that or not, the takeaway is that the last mile to AGI—the last mile of a 10-mile trip that is wrought with all kinds of potholes and mud, analogous to the sudden appearance of vastly superior human intelligence—is primarily about fiddling with the interfaces.

It may not be a plug and play yet. The components exist but we still need to work through integrating the components. The dream is like the electric self-driving car, the major parts exist in good-enough and improvable state to put something viable together. In my case, Python and Java scripts with assists from LLMs and knowledge graphs like Wikidata.org, and LLMs (with translation skills far beyond word-mapping, plus fine-tuning and prompt engineering) are effective intermediaries between the parts.

In the world of what I’ve written, a potential exception is something like Reps, from my 2014–2016 work on Reptile Intelligence / Automata Processor. It was a hefty component for massive parallel rule/pattern recognition, but it ran into roadblocks too (that’s a whole other story). I had worked on an implementation, but that was too many years ago. I don’t see it as crucial now—MLflow and modern streaming engines comprise a substantial core of System 1-style fast recognition well enough.

RAG, chain-of-thought, mixture of experts, and connecting protocols like MCP are the strong core for System 2 reasoning and organization. LLMs play a dual role here in the intelligence of a business—the central component for deeper reasoning/organizing and mortar between other components.

Survival of the Smartest

Lastly, my target audience is those enterprises implementing AI, not those at AI labs/vendors (ex. OpenAI, Anthropic) who invent AI. As a Principal Solutions architect for Kyvos Insights, a vendor of a killer Semantic Layer, which makes sense. My job is to highlight how Kyvos’ semantic layer fits into a modern enterprise’s layer of intelligence.

I wouldn’t say that success among enterprises is only “survival of the smartest”, but it’s at least a major pillar. Enterprises know they are in competition with peers as well as non-peers that want to set a flag on other territory. Like a human, that enterprise needs superior situational awareness, a strategic mind, and the skill of persuasion (thanks, to the late Scott Adams).

The enterprise should be concerned with building superior private intellectual capability, the enterprise-curated strategic asset of all strategic assets, as opposed to simply jumping on the current bandwagon because that worked for others. Obviously, even if we’re all ultimately forced to operate on the same data and execute the same strategies, it’s possible to do more with it through superior intellect. Just like in Texas Hold’em.

Private data and strategies that we hold close to the vest is still the secret sauce to winning in civilized and noble competition. Think in the judo sense of you and your opponent doing their fiercest best so that both can genuinely improve.

Look out for “The Products of System 2” in a couple of weeks (late Feb to early March 2026).