Abstract: TL;DR

Preface—The System ⅈ Origin Story

For my AI projects back in 2004, SCL and TOSN, the main architectural concept centered on how I imagined our conscious and subconscious work. In my notes, I referred to the conscious as the “single-threaded consciousness”. The single-threaded consciousness made sense to me because we have just one body, so there is really just one thing it can do at once. Kind of like a single-core CPU that can really do only one thing at a time, but can simulate doing many things at a time by quickly switching from task to task.

The “subconscious” of my AI platform was intended to run in the background, distributed across a massive cluster of servers (this was the pre-cloud days). The subconscious picked up output emitted from various kinds of devices based on a crazy notion I had been hearing about—”Internet of Things” (IoT), what Bill Gates referred to before 2004 as “the digital nervous system”.

The more sophisticated devices (particularly the Microsoft Smartphones equipped with Windows Mobile) would have been loaded with a light Prolog engine to perform what would later be called “edge computing”. Using Prolog meant:

- A single engine on the Microsoft Smartphone could handle a broad array of logical computation.

- That single engine was based on Boolean logic, arguably the most fundamental component of intelligence and beautifully expresses both logic and data in the same syntax.

- The depth of logic could scale along with the power growing specs of the Microsoft Smartphone or other devices.

- Like XML (simple rules, human and machine readable, robust), Prolog offered the flexibility to customize rules on each device.

I discussed this IoT aspect in, Prolog AI Agents – Prolog’s Role in the LLM Era, Part 2.

The subconscious was meant to do the bulk of the grunt work needed to sort out the mess of outputs from those millions of devices out in the field. (Yes, like Dr. Evil still thinking a million is a big number. Back then the notion of millions of IoT devices seemed crazy-huge back then.) That grunt work triaged what the “deep thinking” single-threaded consciousness needed to deal with.

In this blog, I discuss breaking the subconscious into two pieces. One piece that focused on the proactive exploration, building, and maintenance of a vast network of relationships, and the other piece a network of fast rules (the “fast System 1” part of Kahneman’s Thinking Fast and Slow). I call the former, System ⅈ.

With apologies to Daniel Kahneman for conflating his fantastic psychological intent for System 1 and 2 with AI stuff, this is: “Thinking Fast, Slow, and Probing”.

This lengthy blog follows an SBAR organization:

- Situation — Introduction: The current AI narrative focuses on scaling models, but most intelligence—human or artificial—emerges from long-running background processes that explore patterns, anomalies, and associations before any explicit reasoning occurs.

- Background — Human Intelligence: Human cognition operates as a continuous loop between subconscious integration (System ⅈ), fast learned responses (System 1), and deliberate reasoning (System 2), with the brain’s default mode network quietly assembling experience into stories and hypotheses.

- Analysis — Artificial General Intelligence: Enterprises have been incrementally building this architecture through BI, knowledge graphs, event processing, and process mining, with System ⅈ naturally expressed as large-scale exploration of events, correlations, and processes rather than a single monolithic model.

- Recommendation — Episodic Memory Exercise: To understand System ⅈ, reflect on problems solved only after stepping away—those insights surfaced through background integration, the same mechanism this architecture aims to reproduce in artificial systems.

Notes and Disclaimers:

- This blog is an extension of my books, Time Molecules and Enterprise Intelligence. They are available on Amazon and Technics Publications. If you purchase either book (Time Molecules, Enterprise Intelligence) from the Technic Publication site, use the coupon code TP25 for a 25% discount off most items.

- Important: Please read my intent regarding my AI-related work and disclaimers. Especially, all the swimming outside of my lane … I’m just drawing analogies to inspire outside the bubble.

- Please read my note regarding how I use of the term, LLM. In a nutshell, ChatGPT, Grok, etc. are no longer just LLMs, but I’ll continue to use that term until a clear term emerges.

- This blog is another part of my NoLLM discussions—a discussion of a planning component, analogous to the Prefrontal Cortex. It is Chapter XI.I of my virtual book, The Assemblage of AI. However, LLMs are still central as I explain in, Long Live LLMs! The Central Knowledge System of Analogy.

- There are a couple of busy diagrams. Remember you can click on them to see the image at full resolution.

- Review how LLMs used in the enterprise should be implemented: Should we use a private LLM?

Introduction—Who or What is Thinking the Thoughts We’re Thinking?

System ⅈ is an engineered analogue of the brain’s default mode network. It’s a continuous, background process that maintains coherence, notices deviation, and only invokes deliberate reasoning when required.

The main idea of System ⅈ is to separate a hugely wide array of simple tasks of intelligence from deep and complex reasoning (System 2). System ⅈ is constantly probing a vast space of possibility, while System 2 analyzes the situation in front of us. Both can operate simultaneously, minimally stepping on each other’s toes. System 2 can work on the task at hand because System ⅈ is watching out for surprises out of left field. System ⅈ will inform System 2 of dangers or great opportunities.

Most current AI systems are optimized to answer questions, not as much to notice when new questions should be asked. They excel at fast responses and deliberate reasoning within the realm of known frames, but they lack the continuous background processes that generate insight in the first place. In humans, breakthroughs rarely come from logic alone—they emerge from long-running, massively parallel, exploratory integration of experience that thankfully operates outside of our conscious control.

Without an equivalent of this background processing, AI systems will resist change—reactive rather than anticipatory, confident within the scope of their vast training material, but blind to emerging shifts, anomalies, and missing context. This matters now because the complexity of modern enterprises—and the speed at which conditions change—has already exceeded what rule-based reasoning, static models, and larger language models alone can manage. What’s missing is not necessarily more intelligence at the surface, but the proactive substrate that encourages the intelligence to form at all.

System 1 and System 2

Kahneman’s System 1 and System 2 has been referenced often in recent AI research (even though it’s targeted as concept of psychology), for example, where LLMs and Knowledge Graphs meet. In Kahneman’s original form, System 1 and System 2 describe how thinking feels—fast or slow, effortless or effortful, 2nd nature or deliberative.

In this blog, I’m describing what I’m calling System ⅈ, how answers are produced, trained, and retained in a continuous process. In this view, System ⅈ runs continuously in the background, integrating recent experience into candidate stories. System 2 is invoked when no trained answer exists and explicit work is required. And System 1 is the accumulated and reduced (like an article reduced to a summary) lessons of that work—fast not because it is simple, but because it has been trained, reinforced and validated through real experience.

Intuition for System ⅈ: Zen, Heidegger, and Neurology

Because of my deep interest in Zen, I’m fed many videos and articles on psychology, neurology, and other domains related to cognition that say something like, “Your thoughts don’t come from you.” In the most familiar terms, this is your conscious mind going about its business until you (your conscious mind) are interrupted by some thought. The material frustratingly says, “You didn’t think the thought. So who or what did?”

Of course I thought it. It came from my brain. But it came from a network that the conscious mind does not directly control. At the same time, our conscious choices—what we practice, what we attend to, what we expose ourselves to—shape that background network over time. In Kahneman’s framework, this corresponds to the fast, automatic, and largely subconscious System 1—a vast collection of learned functions that, after long training, allow us to drive a car while carrying on a conversation or play a musical piece without thinking about each note.

That picture works well in a simpler world where life might be tough and unforgiving, but relatively straightforward, like that of hunter-gatherer or nomadic societies. Modern life is different. Our technology and its benefits have made everyday existence extraordinarily complex, such that nearly every minute engages System 2 with some decision, interruption, or crisis. Life today is often chronic, adrenaline-fueled crunch time.

Because System 2 is constantly and morbidly stressed in all of us, fast and accurate answers, deep reasoning/organizing and design tend to get the AI glory, while System ⅈ is mostly forgotten.

Besides Zen, there is a connection between what I call System ⅈ and the work of Martin Heidegger, but it is structural, not terminological. I am not suggesting that Heidegger was describing Zen, cognitive systems, neuroscience, or AI architectures. Rather, if we strip away contemporary labels and avoid getting hung up on jargon, System ⅈ aligns with what Heidegger described as a pre-theoretical way of being in the world.

Heidegger’s well-known example of the hand and the hammer is often described in terms of breakdown, but what matters just as much is what comes before the break. When the hammer is working and the hand is fully engaged, the hammer does not appear as an object at all to us. It disappears into the activity. The person is not “thinking about” the hammer; they are simply building. From a Zen perspective, we are “one with the hammer” and this looks like being fully in groove with the world—action without deliberation, effort without self-consciousness, participation without symbolic mediation. Zen practice actively strives for this mode.

Where Zen and Heidegger diverge is not so much in what they describe, but in how they value the “oneness”. Zen treats this absorbed, non-reflective engagement as something to be cultivated and stabilized. Heidegger, by contrast, treats it as the default condition of everyday life. For him, most human existence already unfolds this way—largely unexamined, largely automatic, largely backgrounded. It is only when the hammer breaks, or something goes wrong, that the world snaps into view as an object of reflection and analysis.

In that sense, Heidegger is not celebrating the pre-theoretical mode so much as revealing it. He is pointing out that we normally live immersed in practical involvement, not that we have achieved some enlightened state. Zen seeks to recover this mode consciously (through mindful practice towards achieving an in-the-zone level of skill) while Heidegger observes that we never really left it.

System ⅈ sits closer to this shared structure than to either tradition alone. It is not reflective reasoning, and it is not symbolic cognition. It is the ongoing, non-deliberative maintenance of engagement: patterns holding, expectations flowing, and attention remaining attuned to what is happening. When something deviates—an anomaly, an inflection, a low-probability transition—the system is forced into symbolic reflection, just as breakdown forces thought in Heidegger’s account.

This is not an orthodox Heideggerian position—he would almost certainly reject the idea of engineering such a mode. But the resonance is structural, not doctrinal. Heidegger’s account of pre-thematic being-in-the-world remains one of the clearest descriptions we have of what a background, non-reflective substrate looks like. System ⅈ is an attempt to realize that substrate operationally, while Zen offers a way to inhabit it consciously.

For Heidegger, the most important distinction is not conscious versus unconscious, or fast versus slow thinking. It is the difference between pre-thematic and thematic understanding. In the pre-thematic mode, the world is already there for us—structured, meaningful, and actionable—before we ever stop to think about it. In the thematic mode, we step back, analyze, describe, and formalize (what I associate with System 2). Much of Western philosophy before Heidegger focused almost entirely on this reflective mode and largely ignored the background one.

System ⅈ is not “fast thinking” (Kahneman’s System 1). It is unthinking participation in structure.

This matters for AI because most systems begin at the level of explicit symbols, tokens, representations, objects, composition, and rules—the reflective layer. System ⅈ starts earlier, with event regularities, temporal coherence, probabilistic flow, and a sense of what normally happens next. That orientation is Heideggerian in spirit, whether I intended it or not. It models being-in-the-process, not reasoning about the process.

Being-in-the-process requires robust sensitivity, which I explore in Thousands of Senses and Reptile Intelligence: An AI Summer for CEP. Many non-mammalian animals rely heavily on something like System ⅈ and much less on the explicit deliberation of System 2. Humans, the smarter animals (ex. corvids, orcas, apes), and increasingly AI agents, layer powerful System 1 and System 2 capabilities on top of this foundation. As a result, System ⅈ is left doing constant housekeeping—reorganizing structure, revisiting assumptions, discarding what no longer fits, and staying attuned to what is happening in and around the system so that the right resources can be engaged when needed.

This is also where System ⅈ differs fundamentally from Kahneman’s System 1. System 1 is still cognitive: heuristics, judgments, and shortcuts. Heidegger—and System ⅈ—point to something prior to explicit, reflective cognition. I try to capture this by saying that sequences generate information, regularity precedes meaning, models emerge before explanation, and attention is called only after deviation. That is a close structural parallel.

System ⅈ runs until surprise, and in turn, surprise invokes higher systems. That alignment is not accidental. It is the same structure seen from different traditions.

To make this alignment clearer, Table 1 below shows four perspectives on the same background mode—each from a different discipline, each doing a different job. Zen shows how these modes can be cultivated or quieted, Heidegger describes how they already structure everyday existence, and neurology identifies their biological correlates:

| System | Zen | Heidegger | Neurology |

|---|---|---|---|

| System ⅈ – Exploration | Lived presence without deliberation; being “in the groove” of activity; action without self-conscious narration | Pre-theoretical, pre-thematic being-in-the-world; absorbed practical involvement as the default mode of everyday existence (often unnoticed, even automatic) | Closely associated with the default mode network: continuous background activity integrating experience, maintaining coherence, and monitoring salience |

| System 1 – Thinking Fast | Trained habit and skill; spontaneous response shaped by practice (e.g., martial arts reflex, musical phrasing) | Everyday coping guided by familiarity and readiness; still unreflective, but shaped by learned patterns | Fast, automatic processing; pattern recognition, heuristics, and learned responses |

| System 2 – Thinking Slow | Conceptual thought, verbalization, judgment; useful but something Zen practice seeks to quiet | Thematic understanding; reflective analysis triggered by breakdown, disturbance, or questioning | Task-positive networks; focused attention, executive control, deliberate reasoning |

System ⅈ can therefore be understood as an engineering analogue of ideas found in Zen practice, Heidegger’s description of pre-theoretical engagement, and modern neuroscience’s account of background brain activity. It is pre-symbolic, pre-deliberative, and temporally grounded.

The Zen angle shows us how engaging into the background process results in the smoothest effort—the zone, flow. Heidegger is almost the opposite, a warning about letting AI exacerbate the dark side of habitually going with the flow.

The Complexity-Driven Unknown

There have been way too many moving parts to track during the recent decades—including parts with minds of their own, eight billion other souls and now along with AI agents. We may not need to worry too much about other critters hunting us for a meal these days, but we still compete with other people and corporations wanting to eat our lunch or metaphorically have us for lunch. Complexity spawns imperfect information—information that is deceitful (a predator camouflaging itself from its prey or vice versa), hidden in a big haystack, or the worst, we don’t know what we don’t know.

So the problem we’re trying to solve is, how do our minds handle complexity? Impeccable logic and methodology alone doesn’t work because we don’t know what we don’t know. We can run three simultaneous modes that live in the same brain:

- System 2, Conscious: Executes deeper reasoning.

- System 1, Subconscious: Executes a fast and statistically network of validated rules.

- System ⅈ, Subconscious: A continuous background process that explores the brain discovering relationships, incorporating real-time information. It throttles itself when System 2 needs the bandwidth,

System ⅈ is a massively parallel, highly-iterative, and highly-combinatorial process. Interestingly, it might not even be intelligent. Just running algorithms—which are machines, not intelligent—until it finds something. It’s like a prospector mostly digging holes until they find what they’re looking for.

In those Zen videos I mentioned earlier, there is mention of the “monkey mind”. If you imagine the nervous energy of monkey, that’s System ⅈ. They are relatively intelligent primates that are about as vulnerable as squirrels (which also have that nervous energy).

System ⅈ is about tackling complexity and the resulting huge problem space and solution space that can’t be tackled through rules and logic, no matter how complicated they may be. Similar to how, barring something like Star Trek’s warp drive, we can’t get to another star system within a few days, most problems can’t be solved in O(1) or O(n) computation.

I chose to call this layer System ⅈ—not System 0 or System 3—because it operates behind the scenes as the foundation for everything else. At birth, it is simple, almost evolutionary: an original, baseline System ⅈ. Over time, as humans took on increasing complexity, this background process expanded as well, giving rise to the distinctly human System ⅈ that supports our increasingly sophisticated mental gymnastics. System ⅈs are massively parallel and painfully recursive by nature.

I use the symbol ⅈ, borrowed from mathematics (square root of -1), where the imaginary unit represents a component that is not directly observable but is essential for structure and coherence in the real domain. Like i in complex numbers, System ⅈ is not something we see in the final output. It operates in the background, shaping transitions and relationships, then effectively vanishes once its work is done. System ⅈ should be “imaginary” in its own way, leading one to wonder things like “Where do thoughts come from?”

Note: I originally wanted to call it System 0, but ran into a few collisions with others using System 0 that don’t completely use it in the way I’m presenting in this blog, but does overlap to some extent in different ways. Further System i refers to the IBM’s “i Series”, but in a very different way.

Aside from a standard package of System 1 recognitions (our innate instincts), our human intelligence is bootstrapped from simple but effective “what fires together, wires together” associations. It’s good enough at first, recognizing sounds, blobs, smells. But eventually our human life outgrows what those simple associations can do. It’s sort of like training an LLM, which can take days to months, but if we were to query it while it’s in training. The answers will be gibberish early on, improve progressively. That’s just like us. People can interact with us at any time even though we’re still learning and training.

System ⅈ is always on, always active, ingesting what’s going on, both proactive and reactive. It continuously explores the space of possibilities while also observing the environment, the effects of actions taken by System 1, and even the ongoing cogitations of System 2. It a major source of candidate thoughts rather than the executor of them, operating as a long-running, stochastic process more akin to evolution than reasoning.

Long before humans had deliberate thought or practiced skills, evolution itself was already running a massively parallel, waste-tolerant search process, discarding most candidates and slowly retaining the few that worked. System ⅈ works the same way—it is not efficient, logical, or time-critical, and it does not demand attention. Instead, it runs in the background, generating candidates, forming tentative stories, testing ideas safely, and pruning what fails. System 1 becomes fast only because System ⅈ was slow first, and System 2 can reason only because System ⅈ supplies it with something worth reasoning about. In that sense, System ⅈ is not a higher form of intelligence, but more like the substrate from which intelligence itself emerges.

Combinatorial Explosion

Life on Earth, the maze of possibility intelligence enables us to navigate, is profoundly complex. With complexity comes combinational explosion. Combinatorial explosions of the physical world are something we need to live with until a super-intelligence (ASI) is reached that found a neat trick—probably extending outside our spacetime—such as superposition and quantum entanglement has done in the quantum computing world. In fact, quantum computing might someday be the answer. But for now, there is no ASI nor advanced quantum computing.

System ⅈ produces tons of false negatives. That is, insights that are useless in the context of the endeavors of an intelligence. False negatives are an inherent side-effect when tackling complexity. Normally, false negatives are worse than false positives. So System ⅈ is liberal in its dot-connecting efforts to avoid missing all the possibilities “outside of the box”.

What we do instead is intelligently constrain the problem space. The problem with that is many false negatives—solutions that are missed because a part of a solution exists outside the constraints we set.

System ⅈ isn’t itself concerned with solving a problem. It “imagines” new dots and connects the dots on a massive map for System 1 and System 2 to formulate rules that implement understanding, compose stories that provide analogy, and organize plans towards resolving a problem. System ⅈ responds to event streams sensed internally from internal processes as well as multitudes of senses as I describe in Thousands of Senses.

We’ll explore processes to address the combinatorial explosion. One example I’m particularly excited about in the upcoming blog, Explorer Subgraphs.

Evolution, Culture, and the Engine of Analogy

Evolution itself has and still is solving problems—not intelligently, but relentlessly. Constrained by physics, chemistry, and competition, evolution explored a vast combinatorial space, discarding most candidates and slowly retaining what worked. The solutions it produced—eyes, limbs, camouflage, nervous systems, social behaviors—were not answers to questions, but stable patterns that survived the pressure of reality. When humans arrived, we did not start inventing from scratch; we inherited a world already full of working solutions. Nature became our first library.

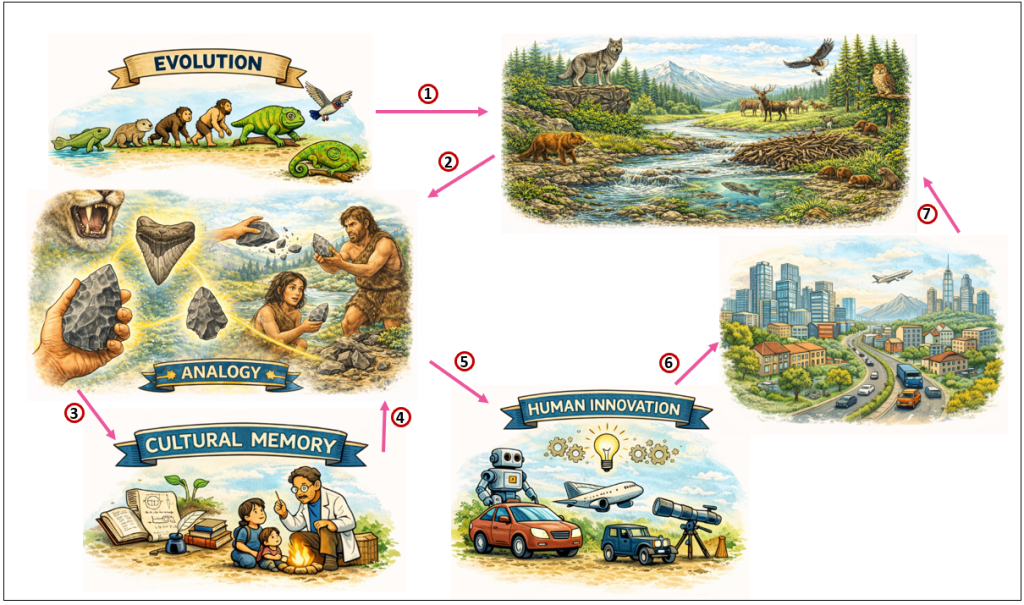

Figure 1 illustrates this process—from evolution to cultural memory to analogy-driven invention that is sourced mostly from our culture:

- Evolution leads to competitive solutions scattered among the creatures of life on Earth.

- The solutions in nature were the seeds of human innovation through analogy.

- Analogy solutions are stored in cultural memory. Cultural memory is text we can read or is passed down from others.

- Cultural memory contributes back to analogy along with inspiration from nature. At first, nature dominated our analogies, but today it’s dominated by cultural memory.

- Analogy is the source of human innovation—our technology.

- Our technology is implemented into the world affecting it.

- Our technological implementations affect life on Earth, which also drives the evolution of non-human creatures.

What makes human intelligence different is not merely that we imitate those solutions, but that we preserve them outside biology. Tools, stories, diagrams, techniques, rituals, and later mathematics and science allow solutions to outlive the individuals who discovered them. Culture acts as a compression layer over experience, storing not just facts but shapes of success: causal structures, trade-offs, and processes. These stored patterns then become seeds for analogy:

- A wing suggests flight, but also lift.

- A nervous system suggests signaling, but also control.

- A river suggests flow, but also optimization.

We test and validate the analogies by “rehydrating” them through experiments, revisiting the source of the analogies—such as revisiting a site, re-reading the book, re-querying a database, and interviewing witnesses. These are all handled by System 2 as part of a thinking process.

Each generation inherits not only biological adaptations, but an expanding catalog of remembered solutions—and it is from this catalog that new inventions are forged. In this way, culture becomes a second evolutionary substrate, accelerating discovery by allowing System ⅈ–like processes to recombine preserved patterns into entirely new domains

The Borg at Yet Another Level

Star Trek’s The Borg offer a darkly humorous, but surprisingly useful, thought experiment. The Borg do not merely collect technologies or link civilizations. They actively seek out and absorb creative capacity across many worlds. Each planet represents a distinct evolutionary laboratory. Life evolves under different physical constraints, ecological pressures, and histories, producing different pools of nature-inspired solutions. From those pools emerge cultures, and from cultures come tools, practices, stories, and ways of thinking. In that sense, a civilization is already an integrated expression of biology, environment, and culture.

The Borg go one step further by treating these civilizations as raw material for assimilation. They don’t just integrate technologies into a shared system. They collapse them into a unified capability, erasing origin and context in pursuit of optimization. That’s what makes them unsettling. But stripped of the menace, the idea highlights that creative inspiration scales with diversity of experience. The broader the set of environments and cultures a system is exposed to, the richer the space of analogies it can draw from.

Human intelligence does this slowly through history and culture and LLMs do it synthetically by ingesting recorded human communication across time and societies. System ⅈ, by contrast, should remain upstream of this—exploring linked and integrated patterns across domains without prematurely assimilating them—so that true novelty can still emerge before being compressed into models, rules, and habits.

That’s the situation. For background, I’ll go over three kinds of intelligence and their corresponding system ⅈ, 1, and 2:

- Human Intelligence: The only real example we are aware of that is at a high level.

- Machine Learning: The “AI” that has been most successfully deployed. However, it’s mostly a collection of narrow-focused tools. But it actually exists.

- AGI: A wider-scoped AI that matches and/or exceeds our human intelligence capabilities.

Human Intelligence

Yann LeCun has said many times: “There is no such thing as AGI. Even human intelligence is very specialized … Human intelligence is not general at all.” He mentions “narrow AI” as well—AI that can only do one to a few things well, such as recommend a video you may like, play chess, and categorize sets of thing. He also includes LLMs, which are very robust, but not the path that will ultimately lead to AGI—AI that will genuinely understand what it’s hearing and saying.

However, for the purpose of this blog and the intelligence of a business, our human intelligence is a “general intelligence” in the context of life on Earth—the geology, the mechanism of evolution, and the current state of the web of life. Human intelligence probably will not work well in other contexts, such as those of sentient entities spanning four or more dimensions. We can’t really visualize something in four dimensional space, much less know how it is to be immersed in it.

But life on Earth is diverse, changing, and ultra-complex. Even if we may not have experienced the vast diversity of life on Earth, collectively, our ancestors have survived it all. So what evolved in humans is a “general intelligence” of life as we know it. No, LLMs alone are not the path to AGI. Rather, they are a major component of an assemblage of AI, as I describe in Long Live LLMs.

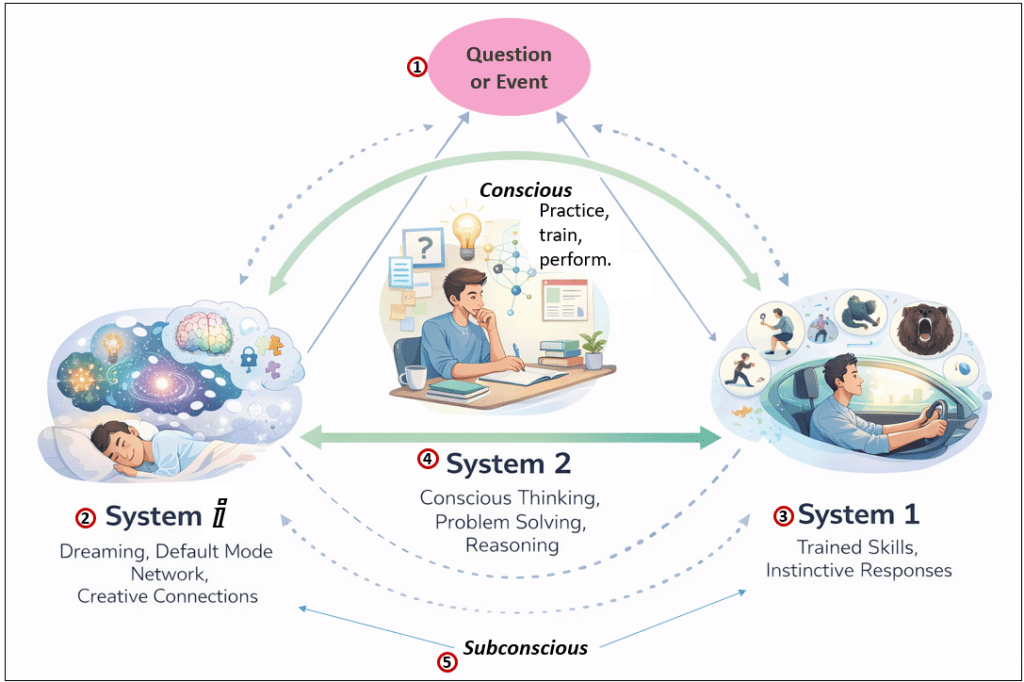

Figure 2 shows human intelligence as a continuous loop between three cooperating systems as opposed to a single “thinking engine”. A question or situation triggers conscious reasoning (System 2), which relies on both deeply practiced behaviors (System 1) and a constantly running background process (System ⅈ). Over time, insights discovered through effortful reasoning and lived experience are consolidated into faster, more automatic responses, while System ⅈ continues to integrate experience into broader narratives that shape future understanding.

- Question and Events are all that we observe through our thousands of senses. It’s also the thoughts generated by System ⅈ. Additionally, a question and/or event can result from exceptions from System 1 (predictions that were wrong) and the thinking process of System 2 (questions that arise from the very act of addressing questions).

- System ⅈ represents the brain’s background integrative processes—active during sleep, dreaming, and default mode network activity, but also running quietly during waking life. It is not logical or goal-directed; instead, it makes wide, speculative connections across recent experiences, emotions, and memories, often forming partial or complete “stories”. Time is not of the essence here—System ⅈ can explore ideas safely, discard nonsense, and surface surprising connections that later become candidates for conscious thought. Its reasoning style is primarily abductive: proposing possible explanations or patterns without yet proving them.

- System 1 consists of innate responses and deeply practiced skills that have become second nature—running from sudden danger, walking, driving, or recognizing familiar patterns instantly. These behaviors feel automatic and fast not because they are simple, but because they have been trained through countless iterations and validated by real-world feedback. System 1 is “conscious” only in the sense that its outputs enter awareness immediately, without revealing how they were produced. It represents the accumulated results of prior learning rather than active problem solving.

- System 2 is conscious, deliberate thinking: reasoning, problem solving, deduction, and induction. It is invoked when System 1 does not already have an answer or when something feels wrong. System 2 works serially, manipulating explicit representations, evaluating evidence, and testing hypotheses. Crucially, it often collaborates with System ⅈ—using speculative ideas or stories as raw material, then refining them logically into defensible conclusions that can later be internalized into System 1 through practice.

- As mentioned, System ⅈ and 1 are subconscious.

I also see curiosity as part of System ⅈ. It’s a subconscious urge telling us it needs us to obtain information to build a new connection.

The Questions and Events (1) is hard to adequately illustrate. We’re immersed inside it. We might think we observe what’s going on in the world, but we’re very much a part of it. It is the physical world and the actions of all those sentient and sapient agents sharing it with us—from a single virus germ, to ecosystems like forests and oceans, to our friends and family, and to hierarchies of social conglomerates of people.

It’s important to note that I don’t believe System ⅈ, System 1, and System 2 as independent “services” that connect in a loosely-coupled manner through APIs, even though brains have “modules”. At least with the AGI version, I believe there is redundancy of function and much overlap.

The Role of the Default Mode Network

The Default Mode Network (DMN) is a set of interconnected brain regions that becomes most active when we are not focused on an external task—during rest, mind-wandering, daydreaming, memory recall, and sleep. It’s a big part of System ⅈ but not all of it. Rather than being idle, the DMN is heavily involved in integrating experience: replaying recent events, linking them to older memories, constructing narratives, and exploring hypothetical futures. It is associated with autobiographical memory, imagination, and the spontaneous generation of ideas. In the context of this model, the DMN serves as a concrete biological example of System ⅈ: a continuously running, non-goal-directed process that integrates experience over time, proposes speculative connections, and prepares raw material that may later surface into conscious reasoning or be consolidated into automatic skill.

As an example, when improving a skill (currently that’s mostly the latest and greatest on the AI world and guitar), I apply Andrew Huberman’s advice. That begins with differentiating practicing and training. When practicing, that means playing a song, scales, or other exercises that I already know well. There is always room for improvement, but it’s actually better if I don’t think about it and just let System 1 take over.

This is in contrast to learning something new. It can be a difficult passage or part of an entirely new style. The idea is to focus consciously on the moves that are new to me. Repeat it. But focus on my finger placement. It’s certainly not “2nd nature” … yet. After about ten minutes or so, just sit quietly for a few minutes. The claim is that your brain (presumably System ⅈ) will rewire.

I’ve known this for many years. I know that if there is a crisis at work, usually a bug in the application and it’s way past my bedtime, I know from experience that there’s a close to certain chance I’ll fix in a few minutes after a night of sleep what might take all night to solve and much of the day to clean up.

Another example is my daily routine. After about a couple hours or so of writing or coding my productivity starts to wane. Meaning, I’ve typed out what was in my head and need new material. By the time I begin writing or coding, it’s like 80% typing. That number gradually goes down. When I notice I’m thinking more than typing, I go for a walk. When I get back, somehow there is a new load of typing to get done.

Business Intelligence Analysts

The model of intelligence I have in mind is not a chess engine or a conversational agent, but the working intelligence of a seasoned BI analyst. Such analysts routinely face ill-defined problems, plan investigative paths under uncertainty, locate and reconcile data across domains, test hypotheses, and deploy results into operational systems.

The scope of problems they encounter is wide, the data is rarely clean, and success depends as much on judgment and sense-making as on computation. In practice, a mature BI organization already exhibits the core properties of general intelligence within the context of an enterprise: perception, memory, reasoning, learning, and action distributed across people, tools, and data.

A good BI analyst is, let’s say, five parts expertise with their tools and technical savvy (math and data), two parts deep domain expertise, and three parts know how systems/businesses work in general. That last part includes experience across a wide variety of domains from which they can draw inspiration.

Each BI analyst is a self-contained system of intelligence. A primary difference between what will be the AGI resulting from my approach is that an AGI has the potential to access many, if not all, data sources and “skills”, and much more resources. The aggregate of the intelligence of all BI analysts in the enterprise is in some manner the intelligence of the business.

But there is friction in that we:

- Don’t have direct access to the thoughts and experiences of others, nor their individual theory of mind.

- Everyone has different situations that bring them to work, that is, motivations that make them tick.

- We’re loosely-coupled to each other without tightly respected APIs. That friction is one of the primary things LLM can provide. It’s the high-end translator that goes beyond syntactic translation.

BI analysts function today as independent systems of intelligence. The ideas explored across my recent blogs—including this one on System ⅈ—focus on mitigating the barriers that isolate those intelligences while progressively encoding their cognitive components into software systems that can think, explore, and learn at enterprise scale.

Of course, I’m biased since I’m a BI architect/developer. But it’s the quality of people reactively resolving problems and proactively optimizing and strategizing that kept me in this field for almost 30 years.

Machine Learning Intelligence (Current)

Despite being into the third year of the current LLM-driven AI hype cycle, BI systems are still the workhorse of anything resembling sort of intelligence (aside from the human workers). BI systems of today have integrated information from across many enterprise domains, resulting in a wide, highly-curated view of how effort flows throughout the enterprise. From that view, BI analysts compose visions of the state and path of the enterprise. And data science teams evolve machine learning models for predicting the how, why, what/when of the intelligence of the business. At the most sophisticated levels those models are integrated into a network of functionality.

I’ve included ML intelligence between human intelligence and AGI because:

- It actually exists: Human intelligence and ML models exist, but AGI doesn’t.

- It’s successfully deployed in our world: It not only exists, but it breached the confines of labs long ago—unlike quantum computers. It drives what’s presented to us on Amazon.com, YouTube, Netflix, and all those ads that magically show up when we talk about something.

- We completely understand how it works: This is unlike how we don’t actually know how human intelligence works. We have a good idea, but we can’t replicate it or troubleshoot it very well. Therefore, we don’t know how it works.

I’m thinking of this as the “current” stable and widely-deployed “AI”. Just machine learning but scaled to systems of models built from data captured across all activity on Earth. Yes, the AI world has moved beyond the “narrow ML” models, to RAG systems. But I chose to use this because it’s the first successful use of AI in the enterprise and contrasts better with both the Human Intelligence we just discussed and the AGI Intelligence we’ll soon discuss.

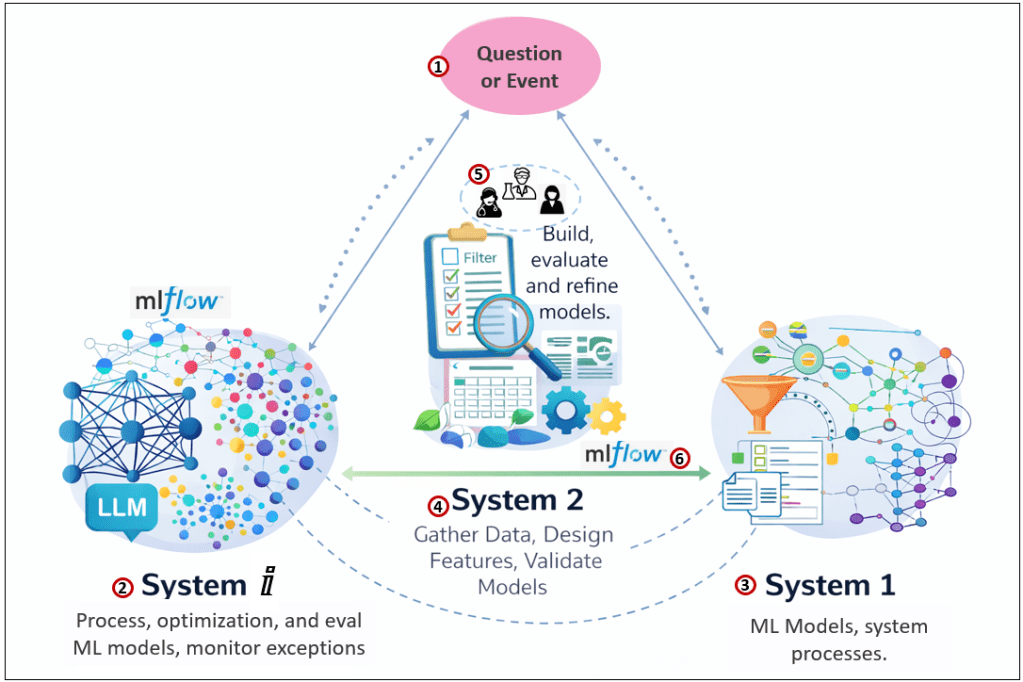

This diagram reframes analytical and enterprise intelligence as a cognitive loop similar to human thinking we saw back in Figure 2. Questions are answered either nearly immediately using compiled knowledge (System 1) or through algorithmic exploration and reasoning (System 2).

In parallel, a background discovery layer (System ⅈ) continuously mines large spaces of data and relationships to surface new candidates for insight. Over time, those insights are formed into validated analytical patterns, ML models, formalized into faster, reusable structures.

System ⅈ also continuously updates existing models with current data, tests the new models and even deploys them.

Here are descriptions of items in Figure 3:

- Question or Event. Like with human intelligence, this is what prods a process. However, the scope of the world from which these questions and events come from is much smaller than the scope of life on Earth.

- System ⅈ is the processing and eval enterprise stack. ML algorithms could be said to be searching for relationships.

- Note that LLMs are here. They are ML models (although not at AGI level), have made headway into the data science loops, and the training is famously intense.

- System 1 represents compiled enterprise knowledge: trained machine-learning models, knowledge graphs, rule systems (such as Prolog), and well-established workflows. These components provide fast, reliable answers because they encapsulate patterns that have already been validated. When a question falls within their scope, responses are immediate and confident. However, System 1 is conservative—it cannot easily adapt to novel situations without help from System 2 and System 2.

- System 2 is the explicit analytical workspace where human data scientists or automated ML systems (ex. MLflow) perform directed reasoning. This includes constructing queries, filtering data, designing features, validating models, and interpreting results. It is where uncertainty is resolved through process rather than intuition. System 2 decides which ideas surfaced by System ⅈ are worth pursuing and determines whether the outputs of System 1 remain trustworthy. Successful outcomes may later be operationalized and promoted into System 1.

- Data Science Team, a cross-functional team consisting of three pillars of perspective:

- Data Scientists: Data scientists design, train, evaluate, and refine analytical and machine-learning models. They explore data to test hypotheses, quantify uncertainty, and turn patterns into models that can be automated, monitored, and improved over time. In an intelligence system, they bridge exploratory analysis and operationalized decision-making, often handing off successful approaches to production systems.

- Stakeholders: Stakeholders define what matters. They articulate goals, constraints, risks, and success criteria—often in business or operational terms rather than technical ones. Their role is not to build models, but to ensure that intelligence is applied in ways that align with real-world objectives, trade-offs, and consequences.

- Subject Matter Experts (SMEs): SMEs provide deep domain knowledge that cannot be inferred reliably from data alone. They validate assumptions, interpret results, and supply context about how systems actually behave. SMEs ground analytical and AI-driven insights in reality, helping distinguish meaningful signals from coincidental patterns.

- MLflow is a lifecycle management platform for machine learning models, designed to track experiments, manage model versions, and operationalize training and deployment. At its core, MLflow records how models are built—parameters, metrics, artifacts, and outcomes—so that learning is not lost between iterations or teams.

Background Processing

Virtually all software applications (including operating systems like Windows) perform background processing. Most self-throttle when something more “important” is going on. Sometimes the background process must insist on taking priority. Those are the processes that go on at night with the users locked out or at least somewhat restricted.

In this case, especially for LLMs, it is intense processing that occupies legions of GPU on legions of servers. An example of a lesser extent is a decision tree where very many versions are tested by hyperparameter, data set.

These background processes are really the inspiration for System ⅈ. They are asynchronous, meaning they don’t block any other activity. The nature of the processing is very well-defined, which minimizes the need for something to step in and fix a problem—which is usually the only time we hear from them.

However, for System ⅈ, we should equally hear from the background processes when it finds something interesting to tell us. For example, telling us about a link it discovered between to disparate phenomenon that presents an opportunity for building a bridge.

MLflow

In this architecture, MLflow plays two complementary roles. Within System ⅈ, it supports automated processing and monitoring: models are trained repeatedly, evaluated, compared, and observed over time as data drifts and conditions change. This background activity is largely mechanical, continuous, and intense, producing pattern signals rather than conclusions.

Within System 2, MLflow represents the handoff point between human intelligence and machine intelligence. Data science teams use it to explore hypotheses, tune models, and decide which approaches are worth keeping. Once those decisions stabilize, the process can be increasingly automated—further moving human-led experimentation towards a “lights-out” pipeline where improvement, selection, and deployment proceed with minimal intervention. In this sense, MLflow is not just a tool for models, but a bridge through which deliberate human reasoning is gradually assimilated as repeatable process and judgment.

When MLflow gained traction a few years ago (2018-2020), it didn’t have the public awareness of LLMs because it hit a population that isn’t all that familiar to the general population, data scientists. The current machine learning system is still “human-in-the-loop”. MLFlow has affected the data scientist crowd similarly to how LLMs will affect coders, writers, artists, and many other professionals.

MLFlow hasn’t yet replaced data scientists, but as it was with other automation tools, it took the low-hanging and mid-hanging fruit away from human workers leaving them with just the high-hanging toughest parts. That might sound like a good thing on the surface, but it just meant they had to work at the redline all the time, with hardly any relatively less intense work to keep them productive but not chronically stressed out.

Monitoring Model Performance

In the machine-learning context, System ⅈ is not only the substrate that processes algorithms during training, but also the background mechanism that continuously observes how those models behave once deployed. Performance—whether human or machine—can be understood in terms of exceptions: prediction errors, confidence collapses, drift, and changes in the rate at which things go wrong.

In human intelligence, this model monitoring could be thought of pain, pleasure, fear, disappointment, even panic.

System ⅈ watches those rates over time, not with logic or thresholds alone, but with sensitivity to deviation, instability, and surprise. When error rates rise, predictions become wildly wrong, or previously reliable models begin to wobble, System ⅈ emits an event—much like an uneasy feeling that something isn’t right. System 1 can react immediately, triggering alerts, fallbacks, or guardrails, while System 2 engages in deliberate work: investigation, root-cause analysis, feature review, retraining strategies, and treatment plans. In this way, System ⅈ does not fix the problem or even fully understand it; it detects that normal has shifted. It is the early-warning system that notices when learned competence is eroding, ensuring that intelligence—human or artificial—remains adaptive rather than complacent.

Artificial General Intelligence

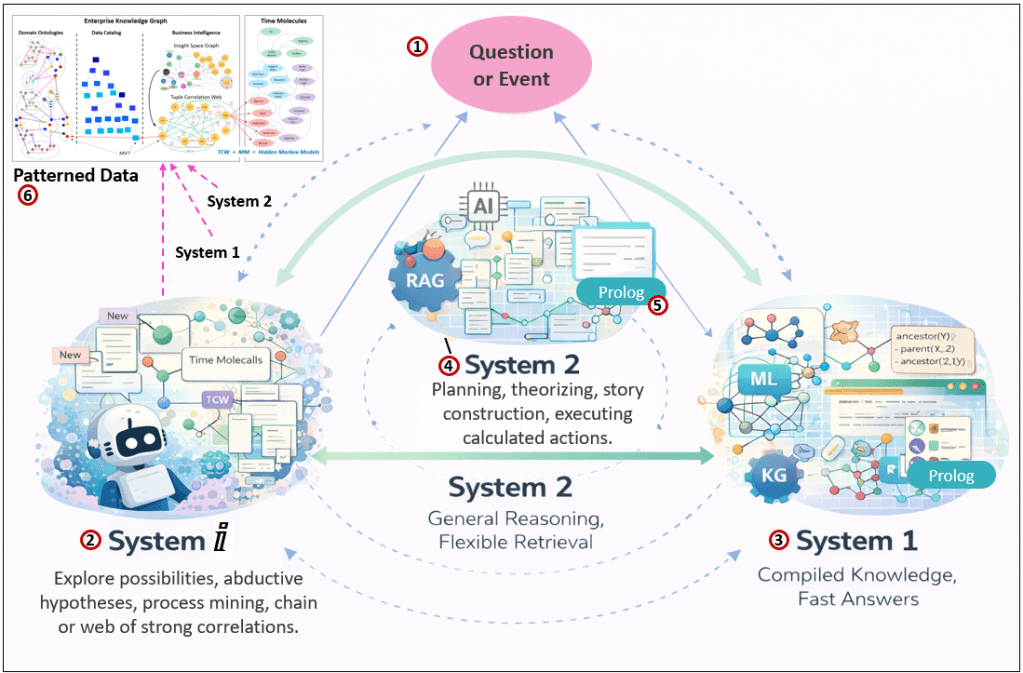

Figure 4 presents an AGI-oriented view of intelligence as an always-running, layered system rather than a single model. System ⅈ continuously explores and reorganizes experience, System 2 performs goal-directed reasoning and model construction, and System 1 delivers fast answers from compiled knowledge. Intelligence emerges not from any one layer, but from their interaction over time.

Here are descriptions of the items in Figure 4:

- Question or Event are what is happening that the AGI can sense.

- System ⅈ In an AGI context, System ⅈ is the asynchronous, abductive engine responsible for speculative processing. It mines candidate explanations, constructs stories, explores alternative plans, and searches for strategies across a wide combinatorial space. This includes activities analogous to dreaming: reorganizing past interactions, testing hypothetical futures, pruning useless associations, and proposing new narratives about the world. System ⅈ is not bound by strict logic and does not aim for correctness—it aims for possibility.

- System 1 contains compiled models that produce fast answers: trained ML models, symbolic rule systems, knowledge graphs, and deterministic inference engines. These components represent what the system already “knows” and trusts. Their outputs feel immediate because the work of discovery has already been done. System 1 is stable, efficient, and reusable—but also limited to what has been previously learned.

- System 2 is responsible for deliberate reasoning and construction. It gathers data, designs features, selects algorithms, tunes hyperparameters, evaluates models, and orchestrates retrieval-augmented generation processes. While large language models may participate here, System 2 is broader than any single model—it is the control layer that decides what to build, what to test, and what to trust. System 2 mediates between speculative ideas from System ⅈ and the compiled capabilities of System 1, gradually transforming exploration into reliable competence.

- Prolog for specific deep reasoning/organizing. Later, I talk about deep reasoning/organizing as a background process.

- The data structures of AGI. This is what will help BI Analysts.

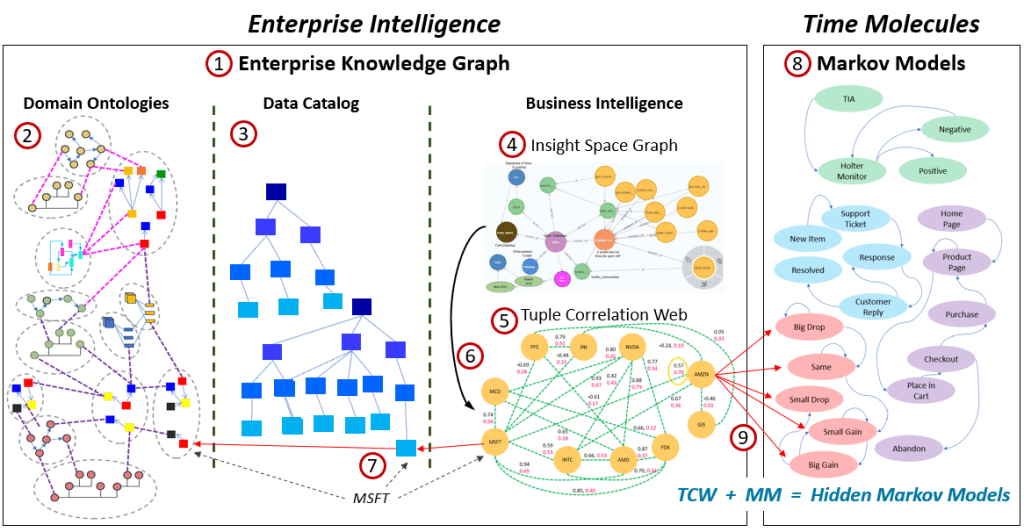

- Enterprise Knowledge Graph: An integrated graph that connects business concepts, data assets, analytical artifacts, and learned relationships across the enterprise. The following items are extensively discussed in my book, Enterprise Intelligence. For each item, I provide the page and chapter.

- Insight Space Graph (ISG): A graph of discovered analytical insights that captures what was noticed, where, and under what context. page 254, The Insight Space Graph.

- Data Catalog: A metadata backbone that maps analytical and semantic concepts to their physical data sources. page 129, Data Catalog.

- Tuple Correlation Web (TCW): A web of observed correlations and probabilistic relationships between tuples across domains. Enterprise Intelligence, page 288, The Tuple Correlation Web.

- Knowledge Graph: A structured graph of entities and relationships defined by explicit semantics and meaning. page 93, Knowledge Graph.

- Time Molecules (Hidden Markov Models) Time-based probabilistic process models derived from event sequences. Time Molecules are essentially learned Hidden Markov Models over event sequences—they encode what normally happens next probabilistically, turning raw logs into a temporal sense of normal.

- Markov Models: Models that describe the probability of transitioning from one state or event to the next.

- Bayesian-Inspired Conditional Probabilities: Probabilities that estimate how likely outcomes change given new evidence or context.

- Enterprise Knowledge Graph: An integrated graph that connects business concepts, data assets, analytical artifacts, and learned relationships across the enterprise. The following items are extensively discussed in my book, Enterprise Intelligence. For each item, I provide the page and chapter.

For AGI or near AGI, System ⅈ can be the processes that are still at least in part supplemented by humans. The task might to beyond the capabilities of the AGI. If we’re talking about ASI, presumably, anything a human can do, it can do better, but AGI might still be intellectually fallible like even the smartest of humans.

An AI could think of it as people doing requiring keen and specialized intelligence such as physics research as a magical black box that can take an awfully long time. Or it can be strategizing a plan that must be designed by a human. In either case, the AGI doesn’t have direct control over the process. It’s kind of like that whole “we don’t have control over what thoughts pop into our conscious mind” (but we control how we react to it) thing I mentioned at the beginning.

Charting the Vastness of a Space

An intuitive model for System ⅈ could be biological exploration. Slime molds that recreate rail networks, tree branches reaching for sunlight, and roots probing soil for nutrients are all examples of massively parallel search processes operating without plans, logic, or goals. Indeed, the axons of our brains probe their local chemical and physical environment during development, extending, pausing, retracting, and redirecting in response to guidance cues rather than following a predefined wiring plan. They explore first and optimize later (in a very primitive manner), reinforcing what works and abandoning what doesn’t.

System ⅈ behaves the same way. It continuously reaches outward across events, memory, and possibility, constrained by pain, risk, and limits rather than rules. It’s seeking noteworthy situations and more importantly, predicting good and bad events. Intelligence emerges not from this exploration itself, but from what later layers choose to retain.

In an AGI context, I increasingly see System ⅈ operating primarily over the Tuple Correlation Web rather than over explicit rules or symbols. I’ve written about charting insight space in a previous blog.

Large-Scale of Sensors

LLMs scale to tremendous heights in terms of the parameters (billions) and volume of training data (trillions of tokens). However, as I wrote in Thousands of Senses, the inputs into our brains are also scaled very high. Although I titled it “Thousands of Senses”, I mentioned that I think it’s more in the tens of millions. For example, each of our retina have millions of rods and cones.

The problem with LLMs training from written material and even other rich modes such as video is that the vast majority of sensory is stripped out. That is, as opposed to ourselves and the things we interact with fully immersed in the physical world.

I’m just suggesting that sentience is a continuum ranging from “conscious as a rock” to somewhere undefined. I assume there is such a thing as sentience more sentient than what we experience. Therefore, human sentience is somewhere along that continuum. That continuum contains a few chasms to jump. And a big factor of the place of a sentience on that continuum is the number of sensors.

Although a foundational theme of what I’ve been writing tends to move beyond reaping benefits from simply scaling up—whether it’s more power on smaller chips, productivity via homogenous mechanizations, or scaling up LLMs—to assembling systems in novel ways, following is a scale-up that’s missing:

For an AGI, I propose it must include an extremely high number of sensors, probably beyond the millions of sensors of a single human. And it must possess the ability to triage (filter out what is not necessary) and/or reduce what is sensed to fewer signals (aggregate multiple signals, i.e. complex event processing). In IT terms, this is implemented as a large-scale, always-on, background, asynchronous, self-throttling, self-maintaining system running relatively simple and straight-forward algorithms.

That’s System ⅈ.

AGI System ⅈ Data Structures

In this section, we’ll dive deeper into the data structures of AGI System ⅈ. It’s item 6 in Figure 4. These data structures are maps, not much different from the maps of relationships, terrains, and chronology in our human minds.

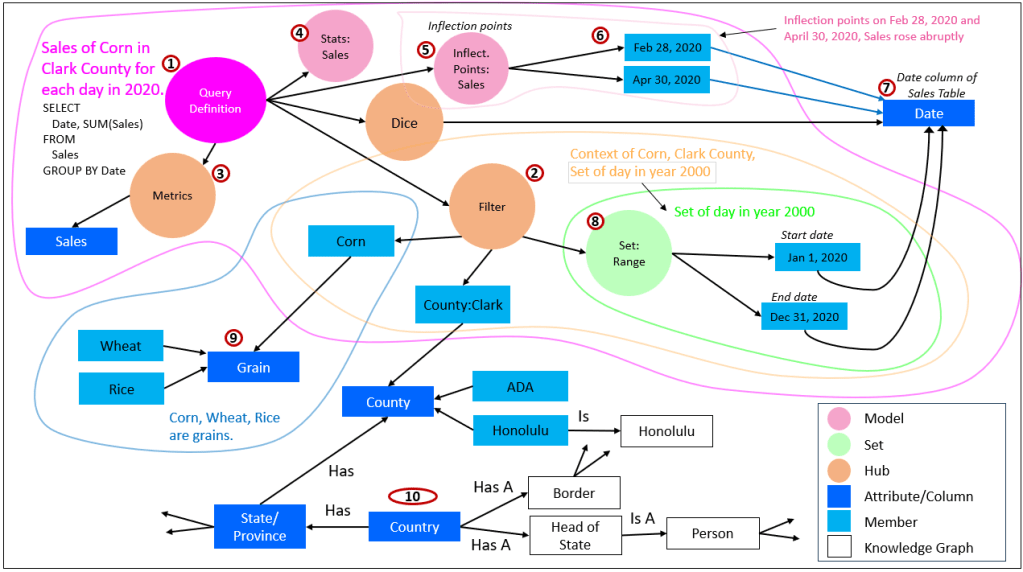

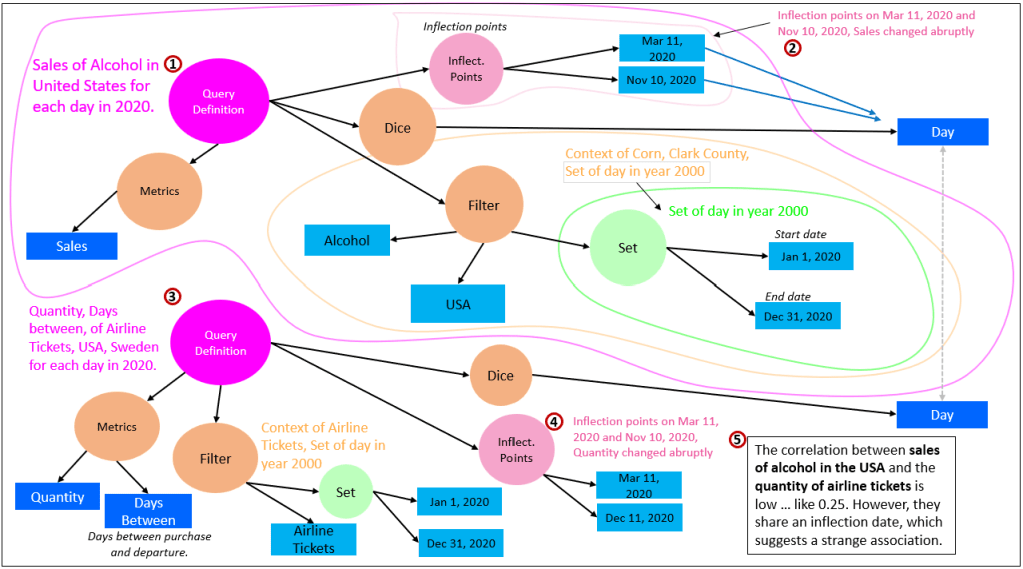

Figure 5 is a close-up of item 6 in Figure 4. Figure 5 also appears in another blog where I describe the numbered items.

It’s important to remember that the Insight Space Graph (4) is automatically updated from BI queries by BI analysts. The Tuple Correlation Web (5) is primarily automatically updated from tuples extracted from the BI analyst queries (6), which can be a System ⅈ process. Table 2 shows how the other structures (2, 3, 8) are generated at least in a partially automated way:

| Component | Automated / System ⅈ-Leaning Capabilities | Manual / Human-Guided Capabilities |

|---|---|---|

| Knowledge Graph (KG) | • LLM-assisted extraction of entities, relationships, and candidate triples from unstructured text • Automated suggestion of symbolic links between concepts using embeddings and semantic similarity • Partial derivation of taxonomies and lightweight ontologies from database schemas and table relationships | • Authoritative ontology and schema design by domain experts • Curation, validation, and correction of inferred relationships • Governance decisions about meaning, scope, and intent of concepts |

| Data Catalog (DC) | • Continuous harvesting of technical metadata via automated scans (schemas, columns, data types, lineage) • Automatic profiling (row counts, nulls, distributions) • Change detection as sources evolve | • Databases and pipelines initially designed and implemented by data engineers • Business definitions, annotations, and semantic alignment added by humans• Stewardship, ownership, and policy decisions |

| Time Molecules (TM) | • Automatic abstraction of raw events into (date, case ID, event type) triples • Scalable, passive capture of event streams across systems• Automated process discovery and process mining tools that infer sequences and cycles (a System ⅈ activity) • Automated construction of Markov models from observed event flows | • Definition of event sets that determine what constitutes a meaningful cycle or process • Interpretation of discovered processes and anomalies • Decisions about which inferred processes matter, and why |

Patterned Data as the Substrate of System ⅈ

In this architecture, the EKG and Time Molecules represent what I refer to as patterned data. This is not raw data nor unstructured text, but computations built from analytically curated BI—integrated across domains, validated by subject matter experts, secured, and presented through a user-friendly and high-performance dimensional model. A central premise of my work is that intelligence, whether human or artificial, should be built on top of this solid BI foundation rather than bypassing it. Modern approaches such as data mesh, data vault, and LLM-assisted onboarding have freed BI from many historical bottlenecks, allowing intellectual energy to shift away from plumbing and toward meaning.

At its core, BI is already event-centric. Fact tables, the core of BI’s favored dimensional data models, are simply collections of events of a specific subject (ex. sales, visits), and analysis is the act of reconstructing coherent stories from those events in order to understand what happened and how outcomes might be improved. Time Molecules formalize this idea by leaning into the one dimension that is ubiquitous across all domains: time. By treating every fact as a time-anchored event, integration across domains becomes possible without requiring brittle semantic alignment upfront. Process mining, while intellectually demanding, emerges naturally from this view—stories are reconstructed probabilistically from sequences of events rather than imposed as rigid workflows.

Within this architecture, the ISG and the TCW are not auxiliary artifacts. Rather, they are large, continuously maintained graphs (by “maintained”, I mean they are continuously grown and pruned) that capture what has been noticed in the course of normal BI activity. The ISG records salience—queries asked, slices explored, visual patterns detected—forming an episodic memory of analytical attention. The TCW captures a web of correlations and Bayesian-inspired conditional probabilities between tuples, without assuming independence or causality. These structures, together with the data catalog that maps knowledge graph concepts and BI objects back to their physical data sources, form a unified substrate of patterned data.

This is where System ⅈ operates. Rather than reasoning symbolically or executing plans, System ⅈ explores these large graphs as fields—wandering through correlations, similarities, and probabilistic transitions much like roots probing soil or slime mold extending tendrils. Strong paths are reinforced, weak ones decay, and most exploration leads nowhere. When a correlation chain collapses—when the field goes flat—System ⅈ may emit a signal that something is missing. Only then is System 2 engaged to retrieve, construct, or validate a relationship using explicit reasoning. System 1, by contrast, mostly reacts to events using compiled knowledge—rules, models, and learned responses—without awareness of how those structures were discovered.

Time Molecules complete this picture by linking event sequences to the conditional probabilities in the TCW through Markov models, forming powerful Hidden Markov Models that encode process memory. Together, ISG, TCW, the data catalog, and Time Molecules provide a patterned, time-aware substrate over which System ⅈ can continuously explore, System 2 can reason deliberately, and System 1 can respond quickly. Intelligence does not reside in any single component, but emerges from their interaction over time.

Data Mesh: The Liberator of the BI Bottleneck

Data mesh and LLMs form a one-two punch that makes the EKG feasible in practice. The EKG requires onboarding of data from the far reaches of an enterprise into the BI system. Data mesh shifts responsibility for contributing BI-ready data away from a small, overworked, and highly specialized central BI team and down to the domains that understand the data best. This redistribution matters because there are only so many skilled BI developers to go around. I describe data mesh more in, Data Mesh Architecture and Kyvos as the Data Product Layer.

LLMs help close that gap by assisting domain-level teams with tasks that are comparatively simple at this stage—local transformations, SQL queries, light scripting, and basic data shaping—where deep enterprise-wide integration is not yet required. In this context, LLMs are especially effective: they accelerate routine BI work, reduce friction in onboarding domains, and allow centralized BI teams to focus on integration, governance, and higher-order intelligence structures rather than hand-crafting every data product.

Data mesh distributes BI work to domains, which is valuable, but it doesn’t eliminate the need for an integrated view—as opposed to just a set of data products. Domain “data products” often resemble the data marts we already know. They are useful locally, shaped by domain semantics, and optimized for domain questions. The hard part reappears at the seams: when the enterprise wants cross-domain questions answered reliably, someone still has to reconcile meaning across those products. Data mesh changes who builds and owns the data, not the fact that integration remains a central enterprise problem.

Kimball’s early answer to this is conformed dimensions, a practical way to map shared entities across domains so facts could be compared and aggregated without semantic drift. Later, Master Data Management attempted to go further by creating “golden records” meant to unify OLTP systems and/or provide an authoritative mapping layer for BI. In theory it was elegant. In practice, it exposed the real problem: it is surprisingly hard to get subject matter experts from different domains to agree on what a customer, product, supplier, location, or account actually is once you collide their definitions, incentives, and edge cases. MDM didn’t remove the difficulty so much as formalize it—and because the work is social and political as much as technical, the implementation pain was often worse than expected.

Machine learning was then applied to MDM—especially NLP and entity resolution—to reduce manual effort, particularly at customer scale. That helped, but it also introduced uncertainty: probabilistic matching, incomplete evidence, and confidence scores that still required human adjudication. At enterprise scale, uncertainty doesn’t go away; it just becomes a workload you have to govern.

LLMs can mitigate uncertainty in a qualitatively different way than classic NLP. They don’t merely match strings—they can synthesize context from messy metadata, descriptions, and surrounding evidence, propose candidate mappings with explanations, and help humans converge on decisions faster. In other words, LLMs don’t “solve” MDM, but they can make the most painful part—semantic reconciliation—less brittle, less manual, and more iterative.

The very nature of LLMs are integration. It integrated the corpus of recorded human communication across countless domains, time periods, and cultures. In fact, it’s further than integration.

Linking, Integration, and Assimilation

In Enterprise Intelligence and my blog, BI-Extended Enterprise Knowledge Graphs, I’ve written about developing pidgin language between human and machine intelligence. A pidgin is a rudimentary language that emerges when people speaking different languages are tossed together and must somehow communicate. I’ll again use the example of Hawaii pidgin to as an example of the progression linking, integration, and assimilation:

- Linking: Workers from different countries migrated to Hawaii to work on the pineapple and sugar cane fields. They would all have their roles, hopefully some effort is made towards comfort.

- Pidgin, Integration: The people across the cultures might learn to do the simple jobs, but in order to improve efficiency and mutual prosperity, they need to communicate. So a rudimentary language forms.

- Creole, Assimilation: Eventually, the pidgin evolves into a formal vocabulary and syntax. The cultures also merge into a unique form. For example, plate lunches and Aloha shirts.

A recurring mistake in modern data architectures is to confuse having everything in one place versus having a genuinely integrated view. An enterprise data catalog or centralized lakehouse can successfully collect assets—tables, files, streams, models, dashboards—but collection alone does not produce intelligence. Integration requires that data from different domains be meaningfully connected: entities aligned, measures comparable, events sequenced, and context preserved. Business intelligence has always been about this harder problem. Its value comes not from storage, but from reconstructing coherent stories across domains in a way that analysts and SMEs can trust.

This distinction matters even more for System ⅈ. A background discovery process cannot operate effectively over a mere inventory of assets. It needs a field of patterned relationships—events tied together through time, shared dimensions, correlations, and conditional probabilities—so that exploration can flow across domains rather than terminate at organizational boundaries. Without an integrated view, System ⅈ would see only isolated fragments: interesting locally, but unable to form broader narratives or surface meaningful gaps. Integration, in this sense, is not an implementation detail; it is the substrate that allows background exploration to function at all.

The distinction between the three terms is critical, so here’s one more analogy, using food:

- Linked: The ingredients required to make gumbo.

- Integrated: The gumbo is prepared, creating a whole that’s greater than the sum of its parts, but we can still discern the individual ingredients.

- Assimilated: The gumbo we eat is completely decomposed into molecules and those molecules are assimilated into us. There’s no hint of any of the ingredients of the gumbo.

AGI System ⅈ Processes

The EKG and Time Molecules shown back in Figure 5 is the terrain, a map of what we know. The AGI System ⅈ processes explore the characteristics of the map and attempt to “terraform” the map.

These recent blogs describe those processes.

- The Complex Game of Planning: Planning is not a single, logical calculation but a dynamic, multi-stage process of exploration, evaluation, and adjustment—where goals, constraints, and partial solutions are continually revised as new evidence comes in, and intelligence arises not from a final plan but from the ongoing coordination of patterns, expectations, and trade-offs.

- Configuration Trade-Off Graphs: Original thinking is about recognizing, encoding, and balancing trade-offs across symbolic and statistical spaces—where Prolog and semantic networks define constraints and relationships, LLMs explore pattern possibilities, and intelligence emerges from aligning both through process-based reasoning.

- Stories are the Transactional Unit of Human-Level Intelligence: Intelligence arises not from isolated facts or representations, but from the construction and manipulation of temporal narratives—stories that organize sequences of events into coherent, relational structures that can be searched, compared, and recombined to solve new problems.

- Analogy and Curiosity-Driven Original Thinking: Original thinking is the act of recognizing structural similarities across disparate process patterns — stitching together lessons from far-flung domains into procedural templates that can be mapped, reused, and recombined to solve novel problems as dynamic sequences of steps.

Genetic Algorithm

As it is with genetic algorithms—and evolution itself is the original genetic algorithm—there are tweaks, mutations, and countless combinations. The vast majority of gene mutations never gets off the ground or is zapped almost immediately. Genetic algorithms don’t promise the best possible answer. At best, they promise that if an answer is returned, it is better than what we currently have, given the time, resources, and constraints available. In practice, “good enough” is not a failure mode, but the entire point.

When people first hear “genetic algorithm”, their minds usually jump to combinatorial explosion. That reaction isn’t wrong, but it misses something important. But it’s not a fully combinatorial explosion—that is, trying every possible combination of every value of every dimension. As I just mentioned, the full space of possibilities is constrained.

For evolution, those constraints are the current state of life on Earth. Every plant, animal, bacterium, environmental condition, and physical law narrows the viable paths available to any gene. And the scale at which this played out is almost comical. On the order of 10³⁰ to 10⁴⁰ individual organisms have participated in Earth’s evolutionary process over roughly 3.8 billion years—well, according to ChatGPT. That still beats the living heck out of the infinite monkey theorem:

If you put an infinite number of monkeys at an infinite number of typewriters, they will eventually type Shakespeare.

Evolution didn’t need infinity, just a ridiculous amount of parallelism and time. Hominids did even better—the technical accomplishment of tens of billions of hominids over a few million years is much faster and efficient.

One could argue that constraining the space of possibilities is itself a definition of intelligence. From that perspective, suggesting that System ⅈ might include genetic algorithms can sound almost circular—we’re embedding a form of intelligence inside a platform meant to explain intelligence. For a brain or AI, the constraints are constrained by a world of rules and the logic/algebra within that world of rules.

The solution space for most problem spaces in the business world we’ve created appears partitionable, because industrial scalability has trained us to think in terms of horizontal and vertical decomposition. We divide data, workloads, and responsibilities so they can be distributed across many servers or teams. This is the familiar notion of parallelism: take one problem, slice it into similar pieces, and process those pieces concurrently. That form of parallelism is real and useful in simple or complicated setting—but it is not the kind of parallelism that matters most when searching for solutions in complex systems.

What tends to get swept under the rug is that complexity makes the relationships between elements fuzzy, nonlinear, and context-dependent. In these situations, the solution is not something that can be cleanly decomposed and recombined from identical sub-results. Instead, the solution space itself must be explored in parallel: many different candidate solutions, with different structures, assumptions, and sequences of steps, must be pursued simultaneously.

Most paths lead quickly to dead ends, some yield “good enough” outcomes, a few turn out to be surprisingly strong, and others produce disastrous unintended consequences. Parallelism here does not mean many workers doing the same kind of work—it means many distinct hypotheses about how the world might be made to work, all being tested at once.

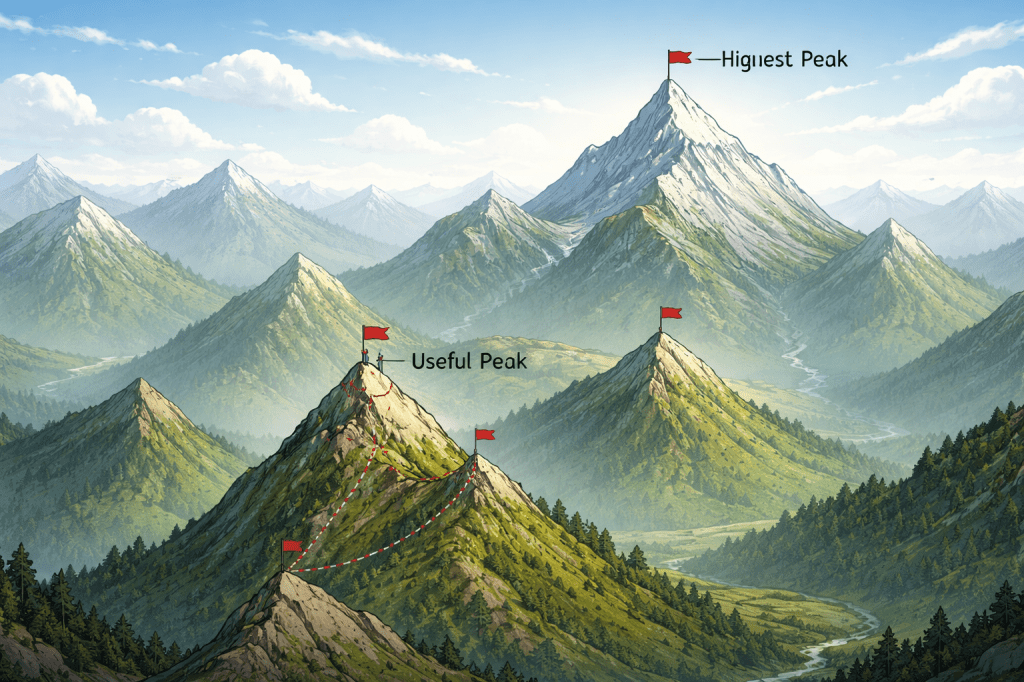

Figure 6 illustrates this reality. Genetic algorithms climb a peak—but not necessarily the highest peak. Evolution spent hundreds of millions of years exploring a landscape shaped by physics, chemistry, chance events like meteors, and relentless competition between genes that can occasionally mix at the species level. The current state of life on Earth is the result of that process—changing continuously, constrained at every moment by what already exists, yet never required to find a global optimum to remain viable.

Lastly, each peak can be explored in parallel, until one is selected, and all the other explorations can be terminated.

Connections discovered by System ⅈ can hit consciousness almost instantly to seconds, hours, days. For a person, this might manifest as something that’s bugging you that you can’t figure out, until after you take a walk and an answer magically appears.

Humanity’s big problems took centuries, even millennia to solve. For humans, because of our self-awareness, we are each a species of one and hope to solve problems well within our lifetime. So we don’t have hundreds to thousands of years to solve our problems. We have until the end of the two-week sprint … hahaha.

We have eight billion brains to distribute a problem across, but managing and consolidating eight-billion threads isn’t possible with us … short of a “Matrix” or Borg scenario … and hardly anyone wants that (at least I hope).

The faster we spin things with new technologies and moving parts, the faster complexity grows, and our ability to find solutions. As I’ve mentioned many times, I strongly encourage you to read one of my favorite books, The Ingenuity Gap, Thomas Homer Dixon.

Even Edison himself often resorted to trial-and-error processes, but with a lot more finesse than the infinite number of monkeys with infinite time. So a System ⅈ that isn’t an elegant O(1) solution still makes sense.

Prolog and Deep Reasoning/Organizing in the Background

Another candidate for a System ⅈ process is deep symbolic reasoning, exemplified by Prolog. Prolog is designed to explore complex spaces of rules, facts, and recursive relationships—often digging far into the weeds of a problem where surface heuristics fail. One of its long-standing criticisms of Prolog is that queries can take a long time to resolve, especially when recursion and large rule sets are involved. But in the context of intelligence, this is not necessarily a flaw. There are classes of problems where an answer is valuable even if it arrives late, and where a provisional or partial result is useful while a better one is still being sought. In that sense, Prolog is well suited to run in the background of an AGI system, continuously exploring deep logical consequences without blocking more immediate behavior.

Seen this way, Prolog-style reasoning complements faster, more approximate processes rather than competing with them. While System 1 responds quickly using compiled knowledge and models, and System 2 reasons deliberately when invoked, a Prolog-based System ⅈ process can quietly churn through dense rule spaces, uncovering edge cases, contradictions, or long chains of implication that are unlikely to be found through statistical association alone. When such reasoning produces something interesting—or when it detects that no satisfactory conclusion can be reached—it can surface its findings as candidates for conscious attention. This reframes “deep reasoning” not as an interactive query-response mechanism, but as a background search for structure, consistency, and overlooked consequences, where timeliness is secondary to depth.

Clarifying Prolog’s Role Among System ⅈ, 1, and 2

This is as good a time as any to clarify Prolog’s role. It isn’t tied to a single cognitive system. Rather, the same logical machinery of Prolog can operate unconsciously, reactively, or deliberately depending on scope, constraints, and attention:

- System ⅈ — Background Prolog (Unattended Reasoning)

Prolog runs as deep, slow reasoning in the background, stewing over large rule bases, long temporal spans, and weak or emerging signals without a specific question driving it. - System 1 — Constrained Prolog (Fast Operational Reasoning)

Prolog operates over small rule bases with restricted recursion and bounded search, acting as a fast decision and validation layer embedded in the web of System 1 functions. - System 2 — Deliberate Prolog (Conscious Reasoning)

Prolog is invoked intentionally for focused, explicit reasoning tasks where the question is known, the scope is controlled, and results must be explainable and inspectable.

Automated Process Discovery as a System ⅈ Function